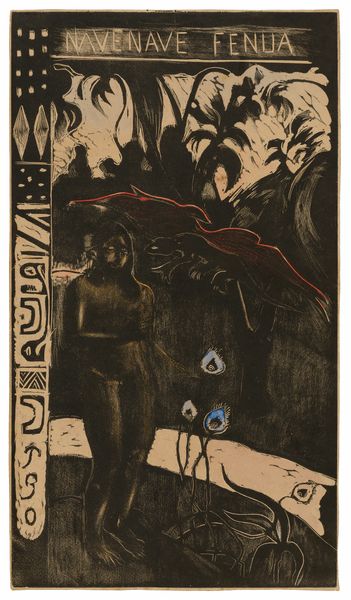

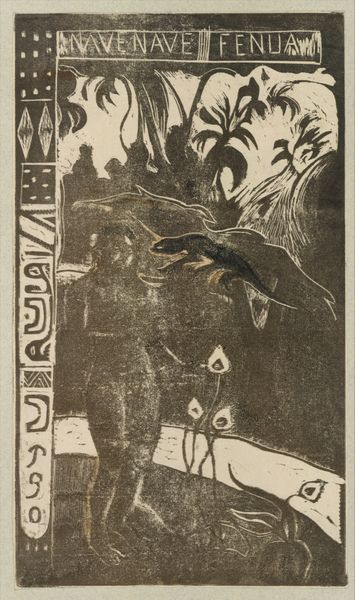

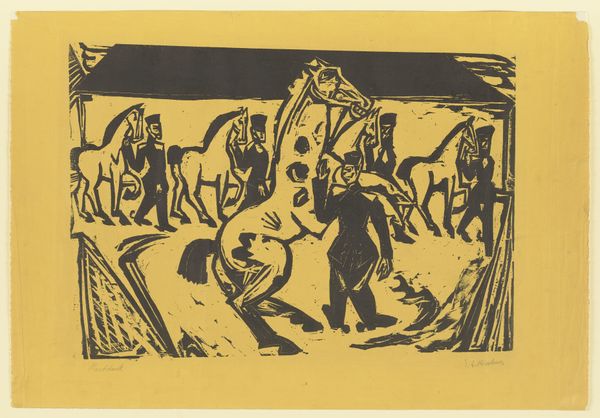

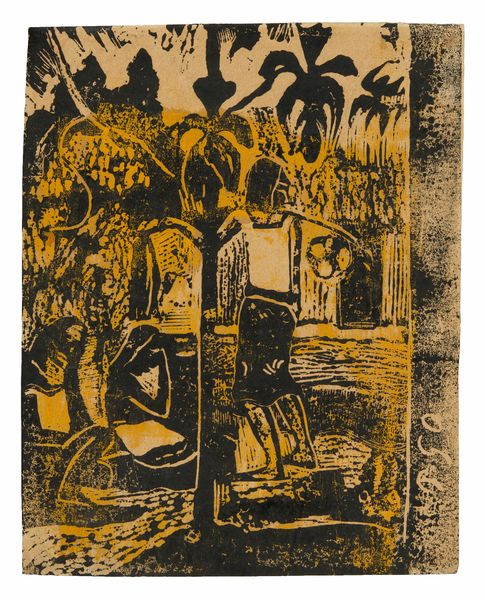

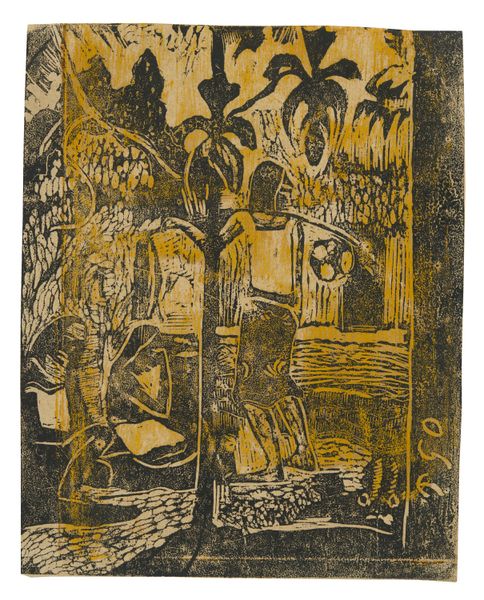

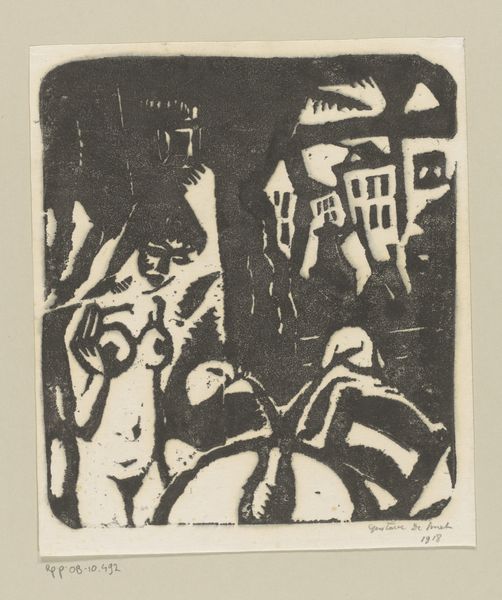

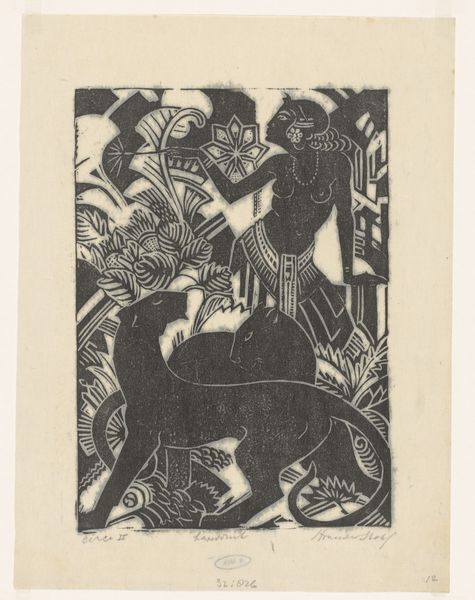

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

#

ink painting

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

coloured pencil

#

woodcut

#

symbolism

#

post-impressionism

#

nude

Dimensions: 13 7/8 x 8 in. (35.2 x 20.3 cm) block

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at Paul Gauguin's "Delightful Land," a woodcut print he made between 1893 and 1894, now residing at The Met. Editor: The title is doing some heavy lifting, isn't it? My first impression is anything but "delightful." Brooding, maybe? Oppressive, even. Curator: You know, Gauguin’s works from this period are filled with this sort of tension. The print showcases a Tahitian woman, nude, standing somewhat rigidly in the foreground. The composition includes lush foliage and what seems to be an idol, all rendered with rough, almost primal strokes. It certainly questions that idyllic image of the Pacific. Editor: Exactly! The process of woodcut itself is quite laborious. Think about the artist physically carving away at the woodblock, wrestling with the material to create this image. It contrasts starkly with the smoothness and ease we might associate with a "delightful land." How does this heavy labor relate to the experience of colonization and representation of Tahiti? Curator: Fascinating point. The woodcut medium itself reflects Gauguin's interest in "primitive" art forms, which he saw as more authentic than Western art. The rough cuts and dark, contrasting tones speak to a desire to capture the "essence" of the island, stripped of European refinement, as he imagined it. There’s something really forceful in it; the almost clunky rendering. It has this immediate emotive quality for me. Editor: And that relates directly to labor! Gauguin, in choosing this process, aligned himself, visually at least, with modes of production outside of the traditional fine art sphere. It’s not just the image but the conscious decision to engage with a more demanding, "earthy" way of making art. Perhaps a critique of bourgeoise consumerism, from paradise, so to speak. Curator: I hadn't considered that connection so directly, but it does lend another layer to it. This isn't a light, airy watercolor painted for Parisian salons; it’s born from the wood, the knife, the very act of creation imbued with a different kind of energy. Looking closer, I now see those shadows dancing differently, it shifts how I respond. Editor: It is also vital to remember the cultural and colonial context. By manipulating and choosing this difficult process, he created the ability to define and reflect how those outside this world view its creation and impact. I wonder about all of the uncredited labor and resource extraction embedded into Gauguin's romantic vision. Thanks for your insights; now I want to look even closer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.