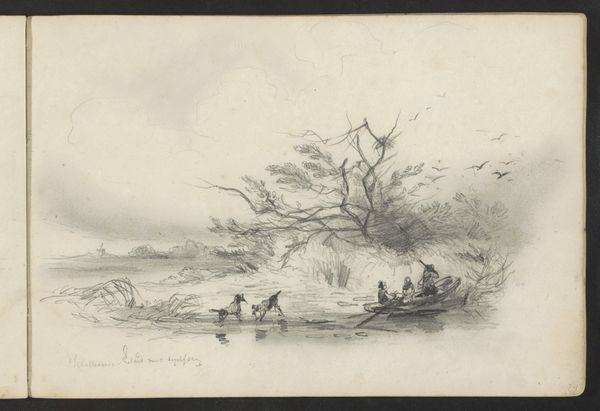

drawing, ink, pencil, pen

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

etching

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

pen

#

pencil work

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

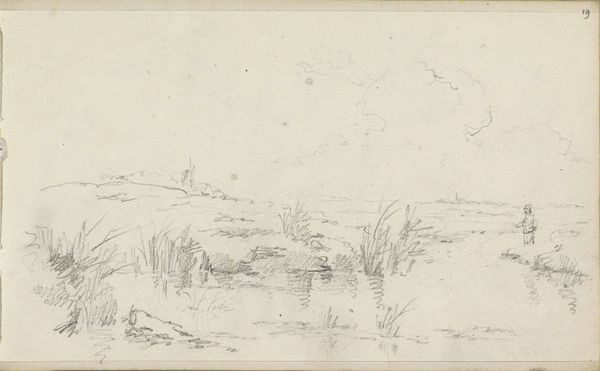

Editor: Here we have Johannes Christiaan Schotel's "Duinlandschap," a landscape drawing likely created between 1797 and 1838, using pen, pencil, and ink. It's so sparse and evokes a feeling of isolation. What do you see in this piece, particularly considering its historical context? Curator: It’s interesting that you felt that mood right away. For me, this landscape, created during a time of significant social and political upheaval in Europe, speaks volumes about humanity's relationship with the natural world. Romanticism encouraged introspection, a turn away from industrialization. Editor: Introspection how so? Curator: Well, look at how small the human presence is, practically erased in favor of the vast, empty sky and uncultivated dunes. This wasn't just about depicting a pretty scene. It reflected the growing anxieties about societal changes, and the simultaneous yearning for a simpler, more "authentic" existence rooted in nature. Editor: I guess I didn't consider how anxiety-inducing that time must have been! What about gender? Is there a reading from feminist art theory? Curator: Absolutely. We might also consider the traditionally gendered association of women with nature, often idealized but simultaneously subjected to control and exploitation. Where would a woman have fit into the landscape depicted, given she would be so far from a town and potential perils associated with the countryside? Schotel's landscape can thus become a site for exploring the complex intersections of nature, gender, and power during that period. Editor: That's given me a lot to consider. It's made me realise how much context shapes our interpretation. Curator: Indeed! Seeing art as more than just aesthetic objects—but as active participants in historical dialogues—can radically reshape how we understand both the art and ourselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.