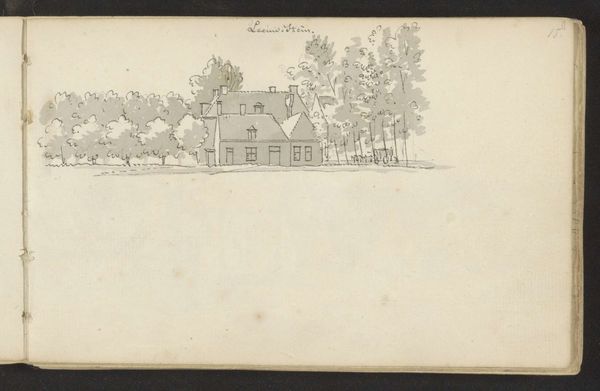

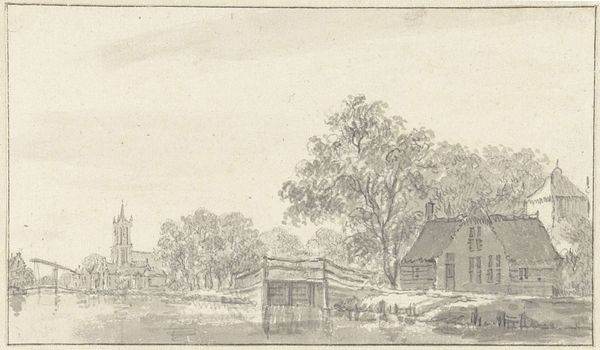

drawing, pencil, architecture

#

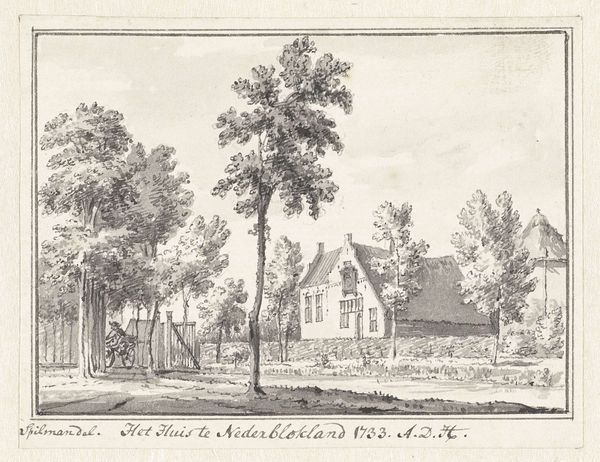

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 207 mm, width 369 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This delicate pencil drawing, titled "Houses on the Palmeniribo Plantation in Suriname," dates back to 1708 and is attributed to Dirk Valkenburg. Editor: My first impression is how stark and somewhat desolate it feels. There's a stark contrast between the carefully rendered buildings and the sparse, almost ghostly foliage. Curator: Absolutely. We must consider that this image depicts a plantation in Suriname during the height of Dutch colonial power. The meticulously drawn houses represent not just architecture, but the infrastructure that supported a brutal system of enslavement. The drawing thus becomes a document, albeit a subtle one, of oppression and power dynamics within colonial landscapes. Editor: And the materiality of the drawing—the pencil on paper—speaks to the economic relationship between colonizer and colonized. What materials would have been accessible for laboring people and what does that say about that social and economic disparity? We need to consider where this pencil came from, what sort of resources were being exploited in other places to facilitate this image production? Curator: Precisely. The drawing is silent about the enslaved people whose labor made the plantation profitable, which emphasizes their systematic dehumanization within this colonial framework. We must recognize their absence in this seemingly idyllic landscape as a deliberate erasure, reflecting the ideologies of the time. It makes me wonder, who was this intended for and what does that context imply? Editor: Yes, understanding who was likely going to see this informs so much, doesn't it? The drawing itself is, I think, a kind of commodity, consumed perhaps by shareholders back in the Netherlands, an almost palatable view of the economic machine running thousands of miles away and fueled by coerced labor and resource extraction. Curator: Reflecting on it, the almost sterile depiction of the buildings makes me very aware of the social relations embedded in that act of creation. Who built the houses? Who owned them? Who was deliberately left out of the visual narrative? It becomes clear the buildings weren't just living spaces; they were power structures in this deeply unjust context. Editor: Agreed. Seeing the landscape of forced labor makes us question who or what other hands are complicit, at the nexus, so that that system can continue functioning. I leave with that questioning echoing more than anything else, here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.