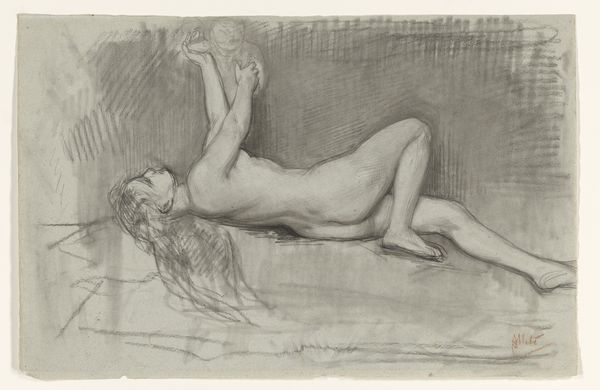

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

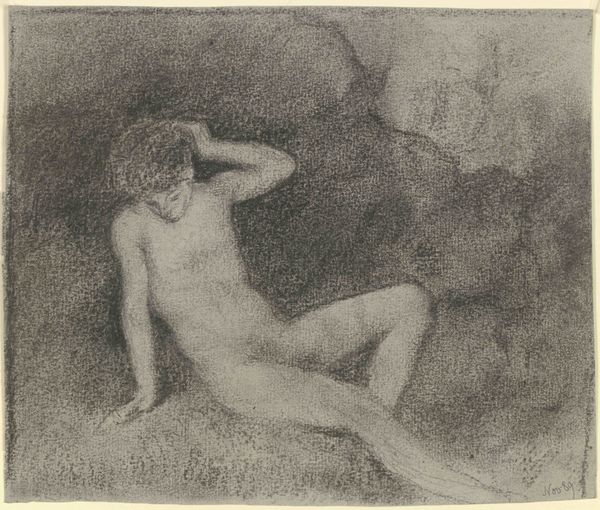

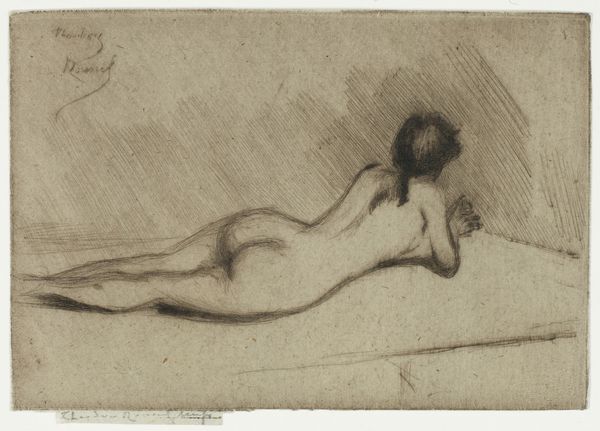

Curator: Willem Witsen created this work, “Liggend vrouwelijk naakt in een interieur”, sometime between 1886 and 1891. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. You’re looking at a drawing employing charcoal and pencil. Editor: It’s wonderfully moody. The shadowy interior creates such a sense of intimacy and perhaps a touch of melancholy, don't you think? Curator: Yes, and consider the paper itself. Its inherent qualities – texture, weight, even its production—contributed significantly to the image. Cheaper paper stock often meant drawings were more accessible, connecting with a broader audience than perhaps oils would. Editor: It definitely has a sketch-like quality— capturing a fleeting moment of repose. The artist's hand is so visible in the varied pressure and direction of the strokes. Almost like a secret glimpsed in charcoal. Curator: The visible hand, the means of production itself, allows us to consider the labour. Witsen moved from looser sketching in the figure’s surrounds, toward an emphasis on defining form, mass, and depth in the figure itself, working perhaps towards a larger painting that never manifested, for example. Editor: The lines almost dance on the page! There’s an inherent vulnerability in a nude figure, and Witsen really captures that. But look closely - there’s confidence too, right? An assertion of presence through pose. Curator: Indeed, and Witsen was well known as part of the Amsterdam Impressionism circle, who also sought to capture a feeling in light of industrial modernization of the area and a return to traditional craft skills. The pose perhaps presents an idealized female figure in her interior space, however domestic workers, for instance, were largely responsible for these interiors; how would we read it with this in mind? Editor: Food for thought, certainly. I’m taking away such a strong sense of intimacy here, something very immediate, yet imbued with questions, so to speak. Curator: A reminder that every object we view bears traces of labor, from the mining of the graphite in the pencil, to the societal implications within. Editor: A perfect way to end this visit – and maybe, invite our visitors to consider that in artmaking and meaning-making, the labor—both visible and invisible—is often what’s most important.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.