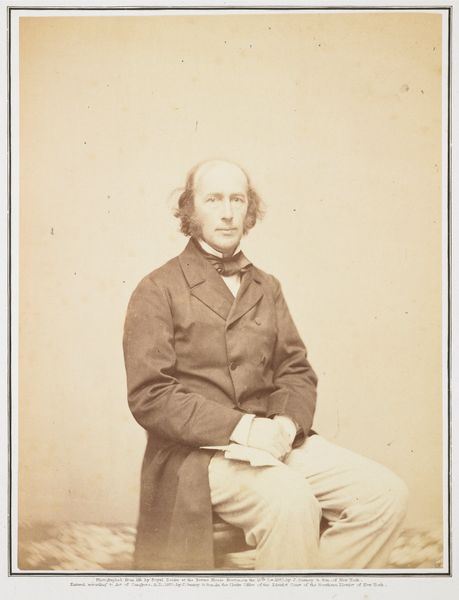

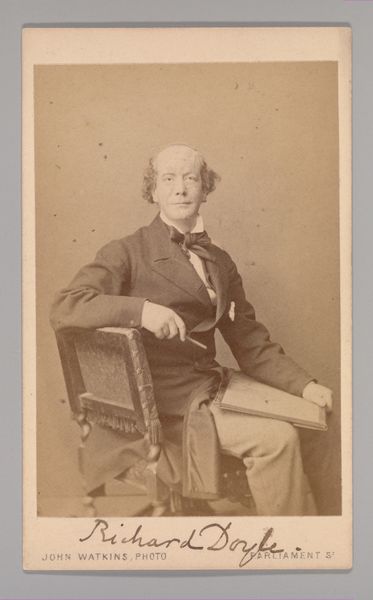

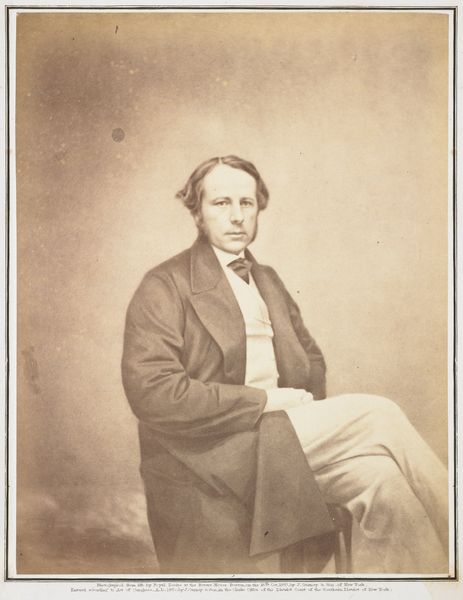

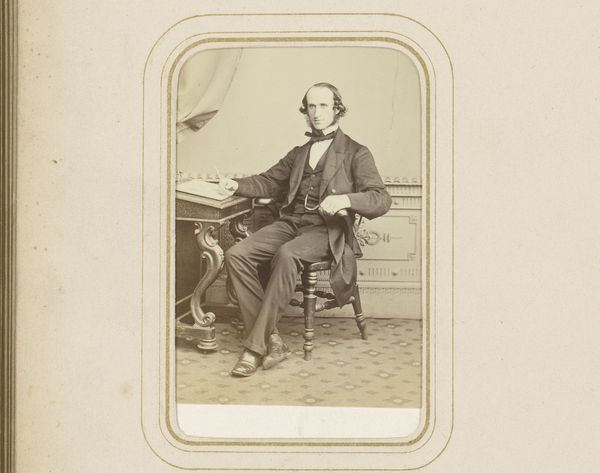

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

19th century

#

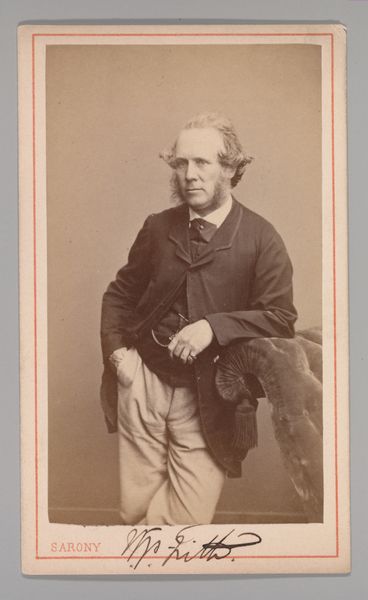

united-states

Dimensions: 5 5/8 x 3 15/16 in. (14.29 x 10 cm) (image)6 5/16 x 4 1/8 in. (16.03 x 10.48 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

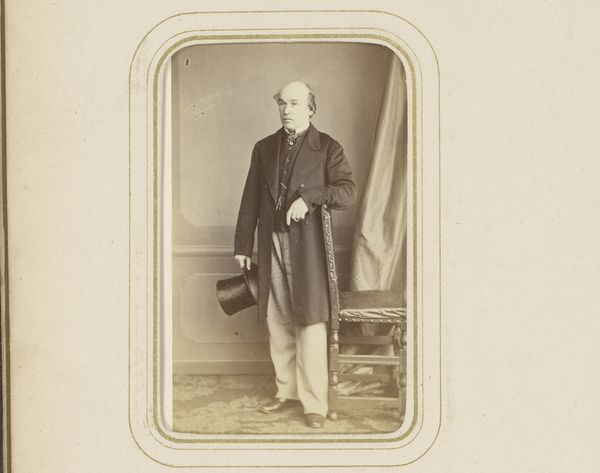

Curator: This daguerreotype, taken between 1858 and 1869, presents us with Edward Davenport. The photographic studio belonged to Jeremiah Gurney in New York. Editor: My initial reaction is one of subdued power. He seems a man caught between weariness and determination. The sepia tones evoke a palpable sense of history, making me ponder the narratives intertwined with this single image. Curator: Daguerreotypes, popular in the mid-19th century, were incredibly unique. They were made on silver-plated copper, making each one a one-off, unlike later photographic processes which allowed for replication. The surface is exceptionally fragile and reflects light like a mirror, connecting past and present. But Davenport's identity...a man of which origins? What shaped the class structures hinted at? Editor: His stance is interesting. There’s a certain deliberate composition to his body language, holding the cane, gazing towards the upper side. This composition creates an intriguing power dynamic between sitter and the gaze. I wonder, how was Davenport attempting to present himself? What did a cane symbolize at the time? Authority, frailty, perhaps both? Curator: Certainly. Symbolically, canes could denote status, and health – sometimes acting as physical supports, and symbols of power and societal expectation. His gaze averted perhaps to suggest he cannot address contemporary challenges directly, implying complicity. Who benefits when portraiture fails to ask those questions explicitly? Editor: The trappings surrounding him–the draped fabric, the classical urn, and goblet – feel carefully chosen, like stage props creating an illusion of timelessness. But beneath the surface lies the quiet rebellion inherent in his glance. These objects denote wealth and cultivate social memory about class and beauty, speaking of access to knowledge through culture and taste. Curator: It’s vital we investigate what such objects cost not just financially but socially. How many were deliberately excluded? The photographic process itself became implicated in how status, and by extension worth, was distributed. Davenport then reflects what we choose to forget even now when looking at those that history has remembered and revered. Editor: Absolutely, these old portraits can feel alienating if we only look at what remains instead of questioning what has been excluded. Thank you. That added layers of complexity to my first observations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.