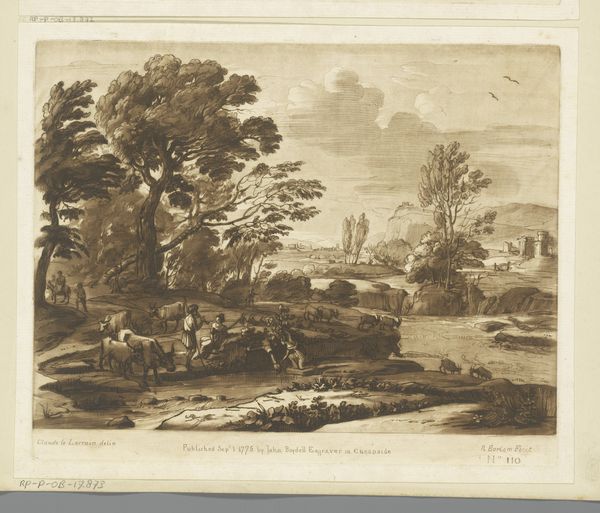

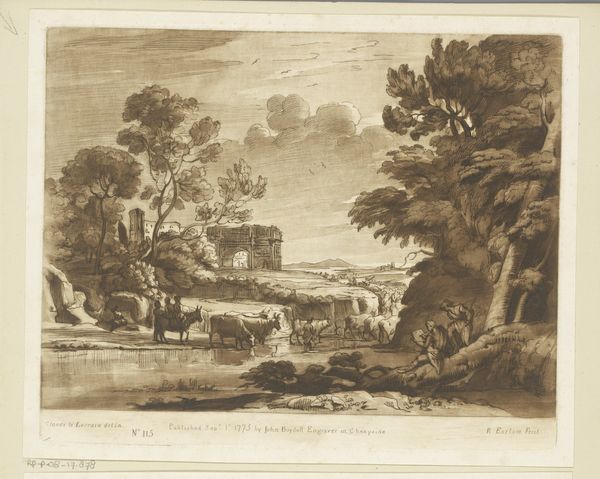

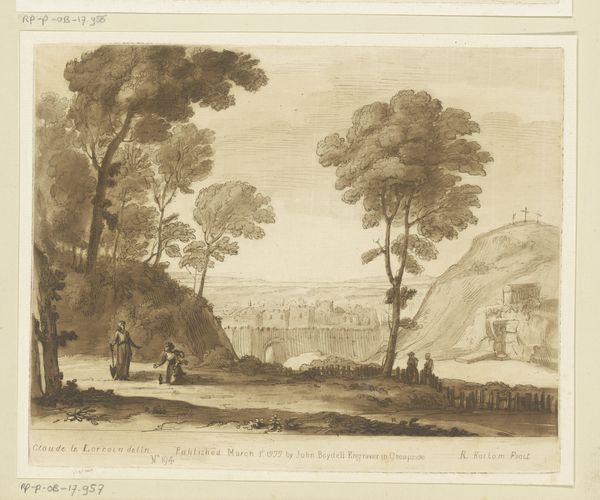

Landschap met ruïne, toren, stenen brug en musicerende herders Possibly 1775 - 1779

0:00

0:00

richardearlom

Rijksmuseum

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's discuss "Landscape with ruin, tower, stone bridge and musical shepherds" by Richard Earlom, possibly from 1775-1779. Editor: Well, looking at this etching, my initial impression is one of serene melancholy. The sepia tones and crumbling architecture lend a wistful air to what is otherwise a pastoral scene. Curator: Earlom was working with reproductive prints after Claude Lorrain here, appropriating Claude’s compositions. But beyond this artistic exchange, there’s a conversation here about the idyllic vision of rural life, set against the backdrop of historical decay. Who has access to these idyllic pastoral scenes, and what systems support them? Editor: The etching technique is crucial here, because it suggests that the romantic vision could be mechanically reproduced and consumed as an art object. Consider also how that connects with notions of labor within the landscape itself, and these musical shepherds become active producers too. Curator: Yes! The seemingly peaceful image hides embedded power dynamics. Who are these shepherds? Where do they exist within the class structure of the time? Are they exploited figures, romanticized for consumption by a wealthier audience? Editor: Precisely. And thinking about the "landscape" genre itself – its affordability and proliferation through prints speaks volumes. Landscape moves from an elite oil painting to a commodity available to a growing middle class. Curator: Absolutely. The image normalizes particular ideals, concealing existing socio-political imbalances within idyllic natural scenarios. The picturesque veils what might be really happening. Editor: Exactly. It makes you wonder about the role of artists like Earlom, who are themselves implicated in this process of romanticizing and commodifying labor. Curator: By situating "Landschap met ruïne…” within this framework, we start seeing that prints themselves carry a hidden socio-political message behind the supposed romanticized scene. Editor: Thinking about its material existence as an etching provides so much context, not only as a pretty reproduction of a popular vision, but a material product in a time of intense economic transition. It opens up so many ways of reading.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.