Copyright: Public domain

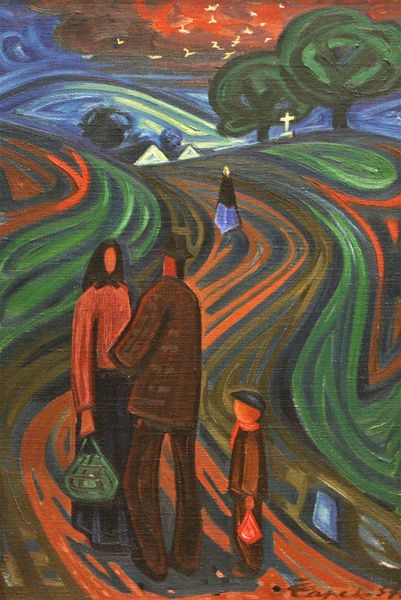

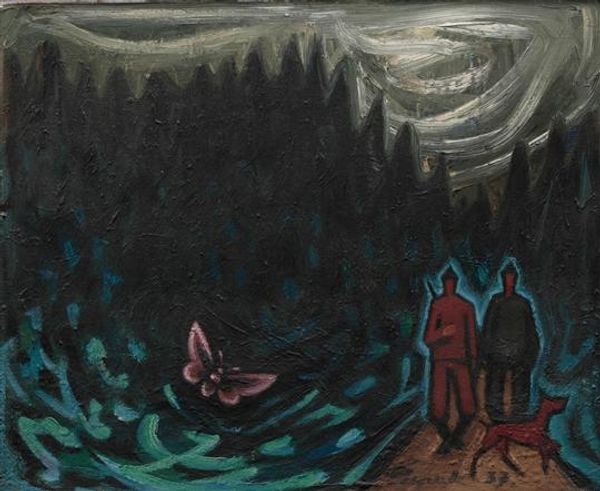

Curator: The earthy tones and distorted forms in this painting immediately evoke a sense of rural unease. Editor: You've tuned right into the emotion I first sensed. Let’s orient our listeners: we're looking at Josef Capek's "Barren Landscape I," completed in 1936. It's an oil on canvas, steeped in the visual language of Expressionism, but with folk-art sensibilities. Curator: Capek was deeply invested in exploring the social and political turmoil of his time, wasn’t he? The interwar years were turbulent, particularly in Czechoslovakia, as it faced economic hardship and rising political extremism. A canvas such as this captures that growing atmosphere of anxiety. Editor: Exactly. These figures, anonymous in their stylized clothing, appear isolated, even threatened by the landscape. Do you find the flattened, simplified forms typical of "naive art" intensify this symbolic weight? Those hooded figures resemble cloaked spectres... Curator: I see that. Capek’s interest in folk art stems from a broader engagement in national identity building. Czechoslovakia, a young country still forging its own identity, sought inspiration from authentic sources. In art, it was connected with the turn away from international avant-gardes towards "art from the people." This trend valorized everyday life, the common man and the vernacular in general. Capek does that too by presenting scenes from ordinary, mostly rural environments, infusing them with subtle symbolism to create work resonant with the nation's ethos and historical experience. Editor: Notice how the children are facing different directions, detached from the group. What does that imagery tell us about disruption? Loss of innocence perhaps? The one on the right seems engrossed in play, while his counterpart stares outwards in confusion. Their postures and gestures imply that disruption comes early in the landscape of social anxieties. Curator: I would add that the historical context enriches those symbols. We cannot forget that Capek himself suffered greatly due to these turbulences: he died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp towards the end of World War Two. Remembering that terrible end gives the work a deeply personal dimension. Editor: Seeing it through that lens adds another layer. Capek captured a premonition of the tragedies to come, translated through the timeless imagery of children and the land that sustains them. Curator: I see Capek’s work now not only as a document of its time but as an embodiment of the anxieties that history too often makes tragically real.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.