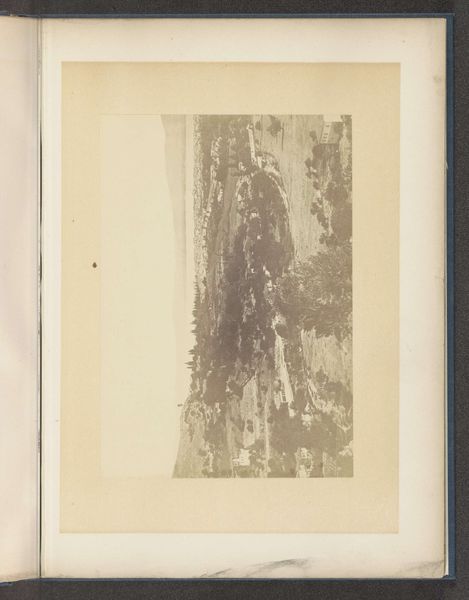

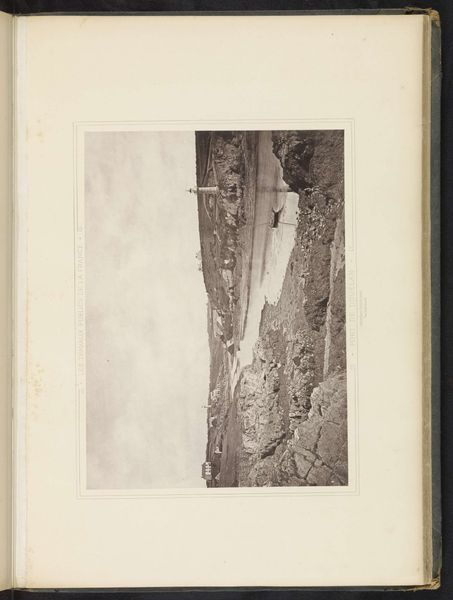

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

realism

Dimensions: height 123 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a photograph titled "Gezicht op ruïnes te Sardis," which translates to "View of the Ruins at Sardis," created by A. Svoboda before 1869. Editor: There's something powerfully stark about this image. The washed-out tones give a real sense of age and the unrelenting sun. Curator: Precisely. Svoboda has really captured the materiality of this site; you can practically feel the texture of the crumbling stone. Considering it's a photograph, the process of development itself is so key – it speaks to the tangible act of capturing light on a specific, manufactured surface, an emulsion on glass or paper. Editor: The way it's framed, almost like a landscape portrait, invites questions about colonialism and Orientalism. It makes you consider what it meant to "own" a view of such a historically significant place, especially given that ancient Sardis was conquered multiple times. How are these ruins symbolic of broader power dynamics? Curator: I see your point about ownership. But, thinking more simply, I am wondering about the equipment, the wet collodion process itself. Hauling heavy camera equipment to remote locales, then processing images on-site – it underscores the labor that goes into image making. What resources were consumed to make this object and bring it back to the "West?" Editor: Right, and the image also reminds me how photography was also instrumental in constructing an idea of the "Orient," reinforcing Western cultural hegemony. Svoboda's image participates in this process by framing the ruins for a European audience, shaping their understanding through this single perspective. Who gets to tell this story, is the thing? Curator: So it's this very tension then – between the indexicality of photography and the layers of interpretation—that make these types of images compelling. One thing is literally captured, but it morphs in purpose over time depending on access and use. Editor: Indeed. The photograph acts as a poignant lens, through which we can consider not just ancient ruins, but how the gaze, both historically and today, shapes cultural narratives. It asks who holds the power, really, in documenting the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.