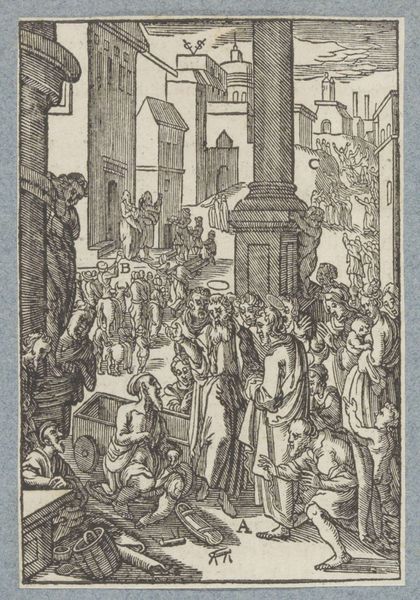

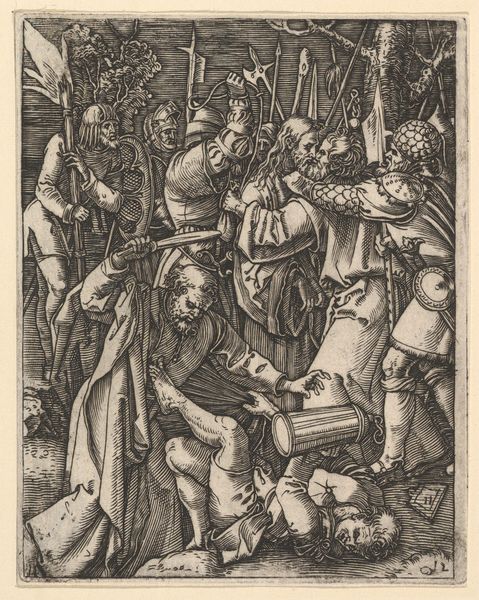

The King of Feuereisen and His Only Daughter, from Der Weisskunig 1775 - 1800

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: Sheet: 8 7/8 × 8 1/8 in. (22.6 × 20.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Today we're looking at "The King of Feuereisen and His Only Daughter" by Hans Burgkmair, created sometime between 1775 and 1800. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It has a heavy feel. That stark black ink on a white background makes the somber atmosphere nearly palpable, and it reminds me of the materiality of grief itself. The graphic qualities suggest to me that the original context of this image was as one in a series. Curator: You’re right, it does depict a funeral procession. It comes from the "Weisskunig," a series intended as a kind of allegorical biography of Emperor Maximilian I. We see it as history-painting that blends personal narrative and dynastic myth. Editor: And the density of that crowd! All those figures, ranked one behind the other; I’m wondering how that production line functioned? What kind of labor division made prints such as these possible, given that this is a woodcut? How many different craftspeople touched it, from design to carving, to the paper manufacture, and finally to the press. Curator: Precisely. Prints like these helped cement Maximilian’s legacy. They acted as a kind of visual propaganda, distributing idealized imagery of his reign to a broad audience. He essentially curated his image through art. Editor: It’s fascinating how that linear style, created by those cuts into wood, allows for such clarity even in the most densely populated areas of the composition. This method highlights each individual, contributing to this scene a quality that's both collectively grand and painstakingly constructed. It forces us to consider what this mechanical reproduction accomplished. Curator: Well, it reminds us that images weren't just beautiful objects during the Northern Renaissance; they were instruments of power, carefully orchestrated and widely disseminated to reinforce social and political structures. Editor: True. The level of work invested into disseminating a specific narrative points not just to technical process but towards larger economic conditions that sustained a print shop practice. Curator: So, beyond a record of a single artist, it's really a record of imperial power and image production. Editor: Yes, and how these forces and materials intersect and affect what is communicated and, especially, how it endures to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.