print, woodcut

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

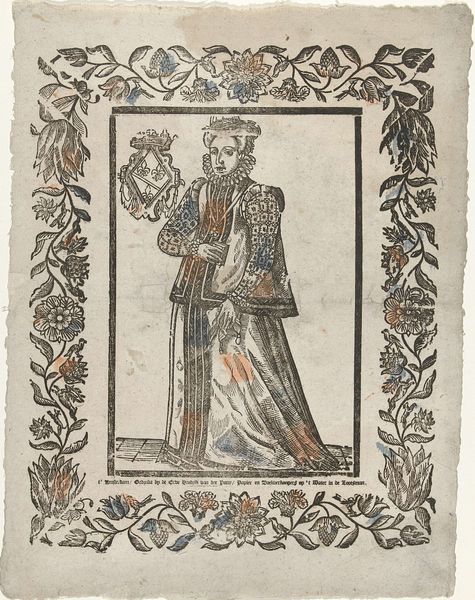

Dimensions: height 133 mm, width 89 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

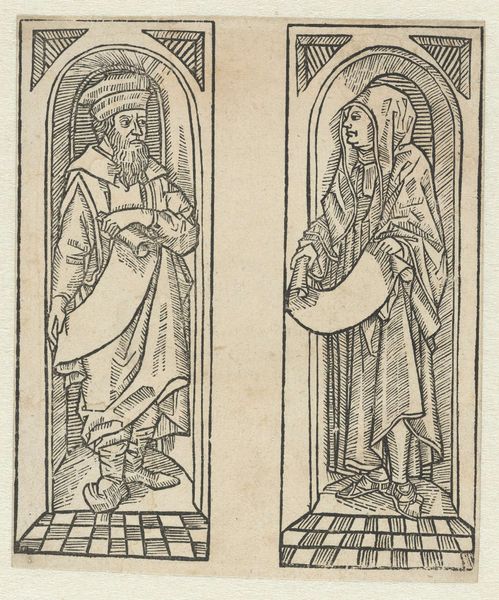

Curator: Standing before us is a rather intriguing woodcut print; a historical scene rendering 'Robrecht I de Fries en Geertruida van Saksen,' likely created sometime between 1517 and 1530 by an anonymous Northern Renaissance artist. The medium is a simple yet striking woodcut, lending itself well to the graphic depiction of the figures. Editor: There's a certain… solemnity to it, don't you think? Despite its being black and white and a fairly rough woodcut, there’s this regal, almost confrontational air radiating from these two figures. He especially looks a little…disapproving? Curator: The figures are indeed quite stately. What resonates is the contrast—a queen draped and flowing away; a crowned prince or king stolidly facing the present and you’re not wrong, something seems to deeply irk him! Let’s explore. Symbolically, crowns indicate power, obviously, but note her head covering. A kind of early version of "modesty," or at least an intended visual of a quiet ruler that stays more as the King’s confidant than ruling outright. Editor: True, it speaks to an expectation, I suppose. It's like she's fading, surrendering space even while present. I imagine all those patterned surfaces might point toward that. He almost completely obscures those types of motifs that show through on her dress—not on him! It looks almost…intentional in the way it shows up only in her characterization and almost absent in him. Curator: The execution is deliberate in making visual that conceptual dynamic: dominance and subservience—these choices must be emphasized in prints destined for wide audiences. The floral crown Robrecht wears feels, perhaps, symbolic of accomplishments... Or does it subtly echo a link with ancient traditions or rulership, intertwining Christian sovereignty with earlier, pre-Christian mythologies, maybe? Editor: It also feels, ironically, sort of feminine. Paired with that scowl he bears, it certainly gives one much to consider about masculine portrayal through symbol. And given it’s a Northern Renaissance piece, you can't forget its relation to early printed images and text as they came back to wider populations in the 1500s… It seems rife for all sorts of ideological uses! I wonder how different cultures consumed pieces such as these? Curator: A tantalizing point! That question alone illustrates the enduring capacity of images to invite contemplation and, potentially, even incite new modes of cultural understanding!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.