drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 149 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

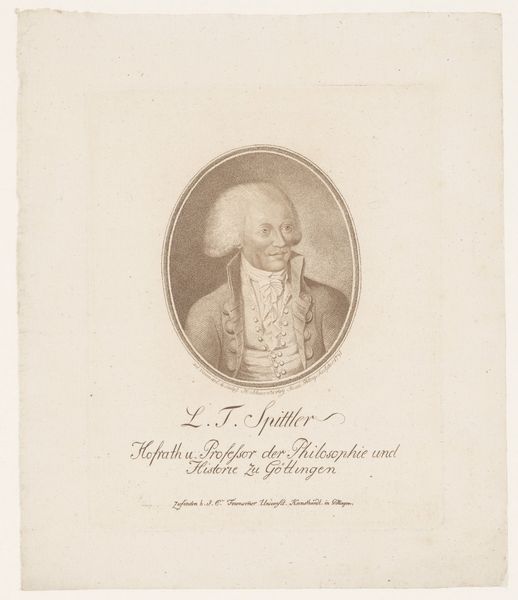

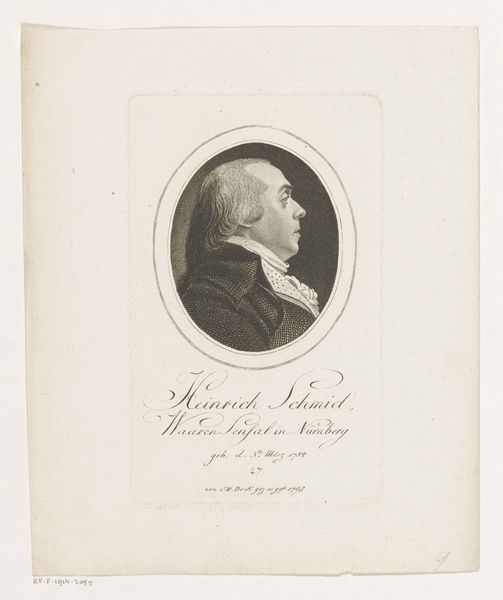

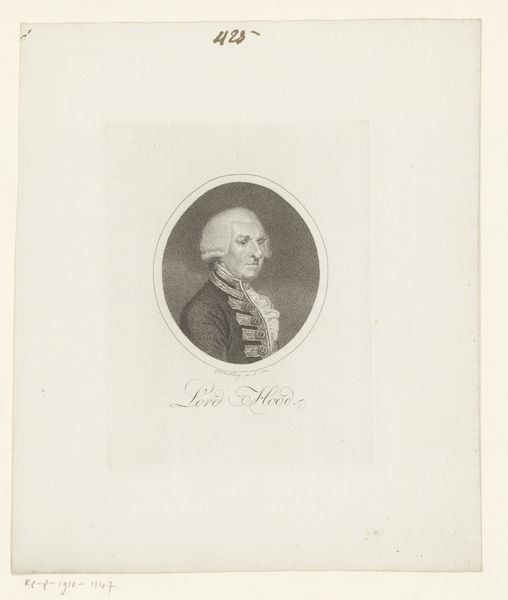

Curator: Heinrich Schwenterley's "Portret van Georg Christoph Lichtenberg," created around 1791, is rendered as an engraving, a print made with ink on paper. There is something about this image that makes it look aged. Editor: The sepia tones evoke a sense of nostalgia, almost a quiet reverence. I’m immediately drawn to the subject’s serene expression and the formal composition within that oval frame. Curator: As an engraving, the act of reproduction becomes integral. This wasn’t a unique artwork meant for a single viewer but rather disseminated widely. I find it interesting to think about how prints democratized access to portraiture during this era, breaking the elite monopoly. And who would have done such fine detailed labour at this time? Editor: Indeed. The oval is a potent symbol of eternity and continuity, quite common in memorial portraits, it seems here to signify not just Lichtenberg the man, but his enduring intellectual legacy as well. His gaze, though in profile, is piercing. His tight updo of his powdered wig, in a neat roll in the back and side, speaks of an internal and controlled power of personality. Curator: Absolutely. And consider the labor invested. Engraving involves meticulous, repetitive movements. It reflects the industrialized process even within artistic creation. It questions whether art can retain aura and value under processes of making. Editor: And don’t overlook the dedication text beneath the portrait, which personalizes the print as a tribute to someone named “Hofrath Kaeftner.” Such textual inclusions are loaded. They indicate circles of patronage, influence and friendship. Was Lichtenberg endorsing him? Is it just an indication of time and relationships within scientific and intellectual German society? Curator: Interesting idea. So what happens with a portrait being reproduced so many times? It's like thinking about it as an early form of mechanical reproduction, impacting not just the reception but also the valuation of artistic skills themselves. It really emphasizes production. Editor: Precisely, and how it serves memory. The circular format, combined with dedication, speaks of continued honour within closed circles. The symbolic vocabulary deployed ensures Lichtenberg’s place. What does all of that mean? The past always continues its relationship to our own modern days. Curator: Thank you. Seeing it this way shifts our understanding of not only what's shown in the art piece but what is around and about it, too. Editor: Yes, this piece helps us appreciate that even in portraiture, symbolic intent always makes its mark, consciously or unconsciously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.