oil-paint

#

portrait

#

cubism

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

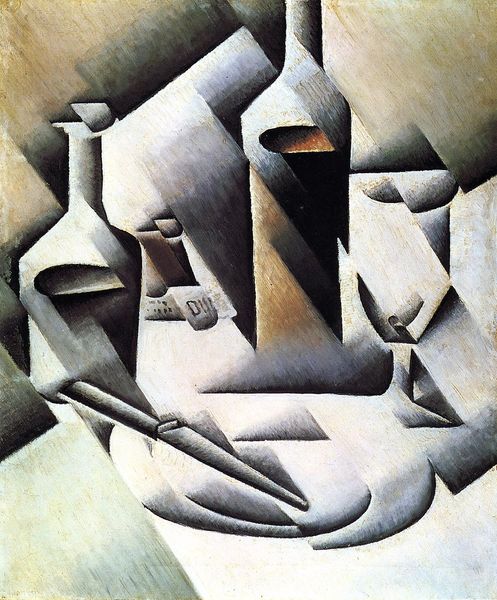

geometric

Dimensions: 48 x 33 cm

Copyright: Public domain

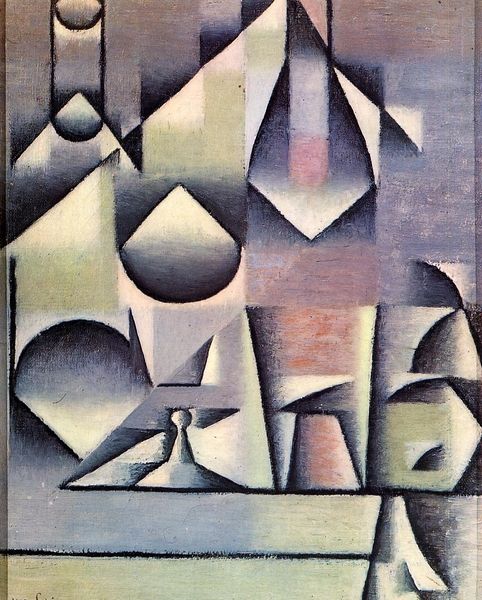

Curator: Before us we have Juan Gris’s “Still Life with Oil Lamp,” created in 1912. It is currently housed at the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands. Editor: Well, my initial impression is one of… coolness, perhaps? The subdued palette of grays, whites, and browns gives it a sort of intellectual detachment, despite depicting such mundane, everyday objects. It’s Cubism doing what Cubism does. Curator: Exactly. Gris, positioned within the Synthetic Cubist movement, was keen to collapse object and ground, disrupting our perception of material reality, of what labor or its instruments might look like. But beyond formal experimentation, there’s a broader social narrative at play. These were tumultuous years in Europe, just before the First World War. How do you see the connection here? Editor: The materials tell a story of production, right? Oil paint itself speaks to a growing industrial economy. Notice how he's flattened the space, almost negating any hierarchy between, say, the lamp, and the table it sits on. Are we looking at tools of labor being reconfigured and destabilized just as traditional labor was shifting and reorganizing? It certainly gives pause about whose hands these items are being touched and made by. Curator: Absolutely. Gris challenges the artifice of the bourgeois home—a disruption echoed by contemporary social movements challenging class structures, race, and colonial dominance at that time. Look closely; can you almost sense echoes of workers toiling to furnish spaces or their exclusion from leisure represented here? It prompts essential dialogues on art, commodity production, class disparity, gendered labor in households... Editor: What I appreciate is how he manipulates the surface with gradations of shadow to articulate a plane and mass which creates an actual, not simply depicted, material dimension to this domestic array. There’s so much more to Cubism than simply representation, even if that is fragmented and multiple. Curator: It's a striking example of how close attention to production methods in 1912 can expand to critical discussions surrounding politics, power, and subjectivity still essential for art interpretation now! Editor: It truly forces one to look and reconsider materiality that lies just beneath, in fact within, all paintings—be that brushwork or a reflection of social order.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.