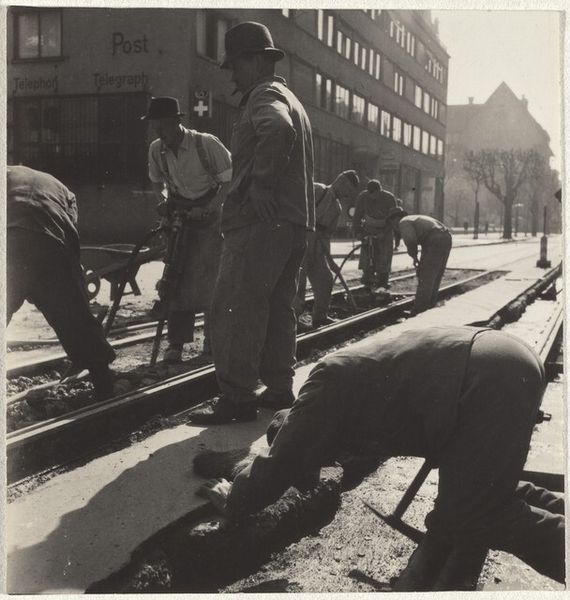

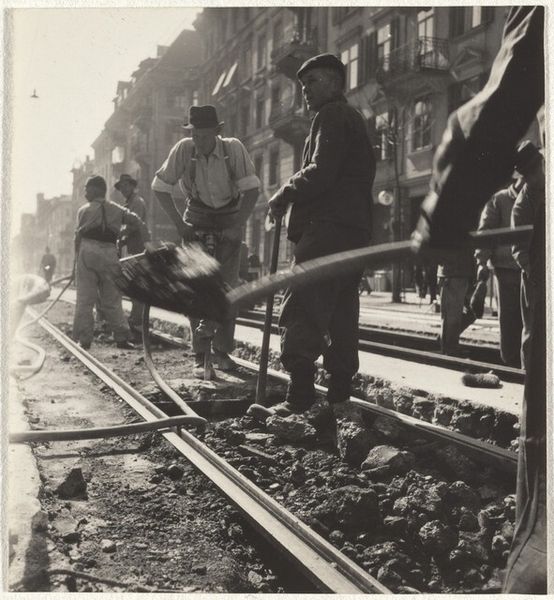

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 5.8 x 5.6 cm (2 5/16 x 2 3/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

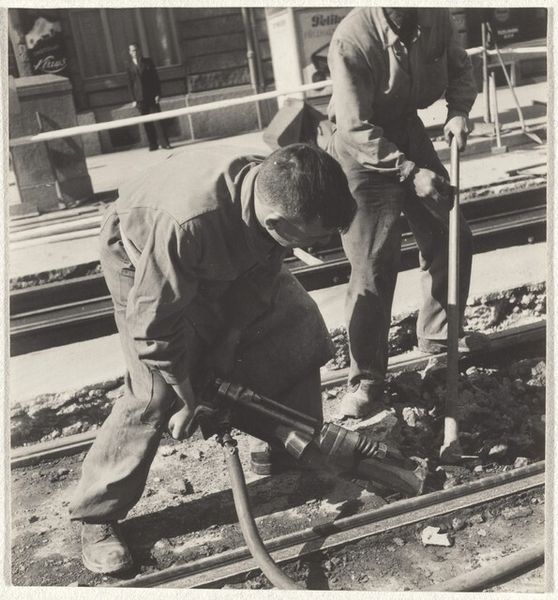

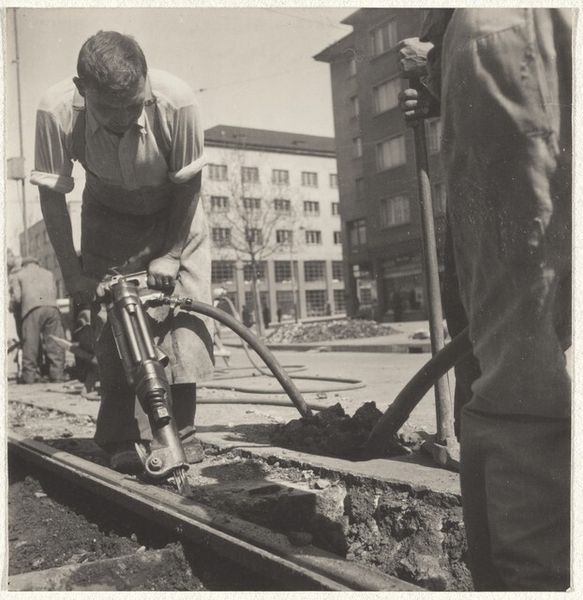

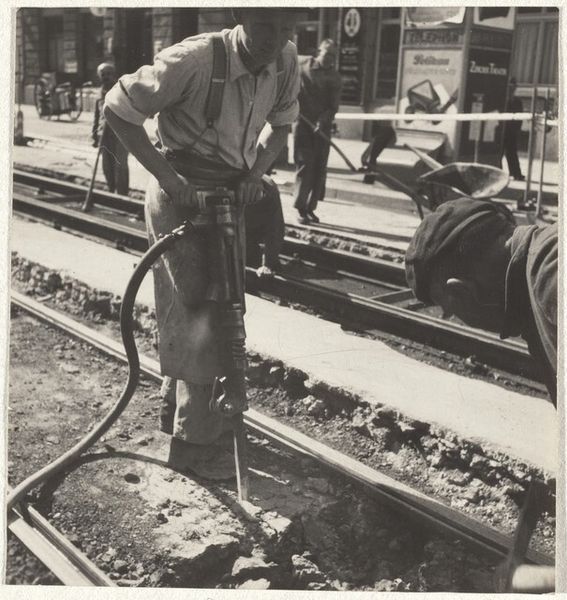

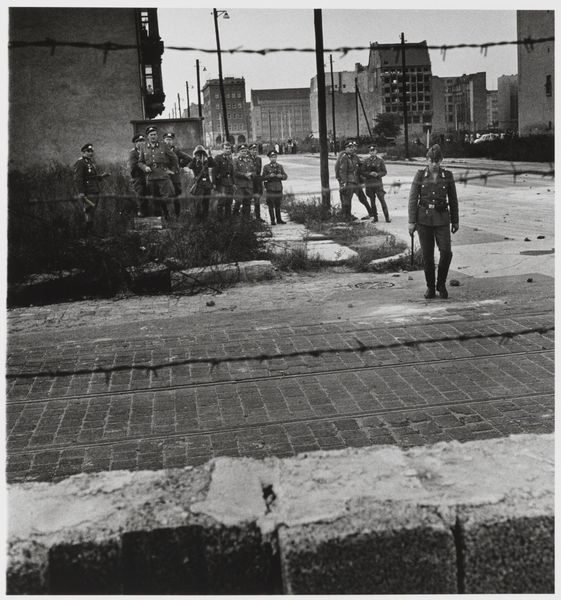

Editor: So, we have Robert Frank’s gelatin silver print, "Laborers--People," made sometime between 1941 and 1945. It’s a stark, black and white image of workers, looks like they are fixing or laying tracks. There's a real sense of...labor here, the toil. What catches your eye? Curator: The image's power rests in its straightforward portrayal of labor, characteristic of the Social Realism movement. Given the period, shaped by war and economic hardship, Frank’s work can be viewed as a commentary on the dignity, but also the dehumanizing aspects of physical work, particularly in public spaces. Note how the framing reduces the figures to shapes, almost anonymous. Do you get a sense of their individual stories? Editor: Not really, they blend into their tasks and surroundings. Is this anonymity intentional? Curator: Possibly. Social Realism aimed to depict everyday life, often focusing on the working class and the poor. By obscuring individual identity, the artist broadens the representation to an entire social group. The image, displayed in a gallery, participates in constructing an idea of ‘the worker.’ Consider too, who is absent – who decides which laborers and which activities are framed? Who is outside the frame? Editor: So, it’s not just showing work, it's commenting on who gets seen, and how? I hadn't thought of it that way. Curator: Exactly. The social and political contexts are vital. The power of art often lies not only in what is depicted but what is implied about society, power, and representation. Editor: This really gives me a new angle for seeing it. I will never look at photography the same way again. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure. Remembering that every image, even the seemingly most realistic one, involves choices, and reflects perspectives is a valuable takeaway.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.