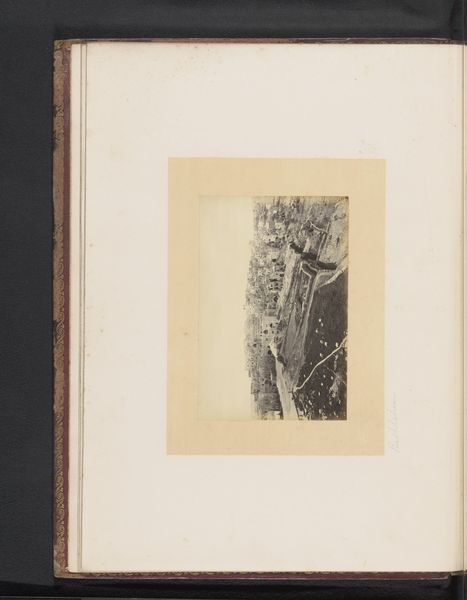

photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is Francis Frith’s photograph, "Gezicht op de Sfinx van Gizeh en de Piramide van Chefren," dating back to before 1875. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is of sheer mass. The imposing scale of the structures really dominates the frame, even in this small albumen print. You can almost feel the weight of the stone. Curator: Frith was a major figure in nineteenth-century photography, particularly noted for his documentation of the Middle East. This image, steeped in Orientalist aesthetics, also reveals the social dimensions of early photographic practices. We need to think about how images like this influenced perceptions of Egyptian history and identity. Editor: Exactly. Looking closely, it makes me consider the actual physical labour. The quarries, the transportation, the raising of each individual block. It’s mind-boggling to imagine the human effort that went into the pyramids. Curator: And who were those humans? Whose hands shaped this monument, and at what cost? Feminist theory demands we excavate the roles of marginalized figures in this grand narrative. Were there female laborers, artisans, whose contributions history has chosen to ignore? What was the status of the workforce in the making of the Sphinx? Editor: The materials are compelling too, I think—these ancient limestone blocks, reshaped, refashioned, revealing striations, almost a grain like timber that makes them a product of specific quarries, places, labour. How much of what we are viewing is simply geology? And then add to that the human exploitation to achieve these aims. Curator: It highlights how representations can reinforce or subvert existing power dynamics. Images like Frith's contributed to both the romanticization and the objectification of Egypt within Western imagination. It begs the question how we navigate this visual legacy ethically today. Editor: When considering this photographic method, it feels critical to explore Frith's working process and this colonial dynamic between artist, subject, and consumer. By thinking about the conditions that led to the image's creation, it may become more approachable. Curator: Reflecting on it, I'm struck by the enduring relevance of this photograph. It stands not just as a record, but as an invitation to interrogate our past. Editor: And, it urges us to remember the physical cost, the tangible labour, that's embodied in these structures, even in a simple photograph like this one.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.