photography, albumen-print

#

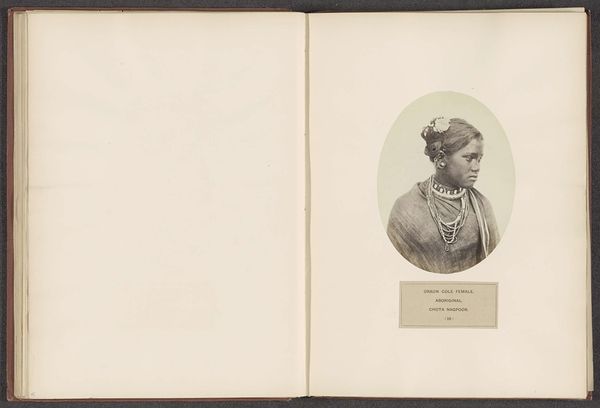

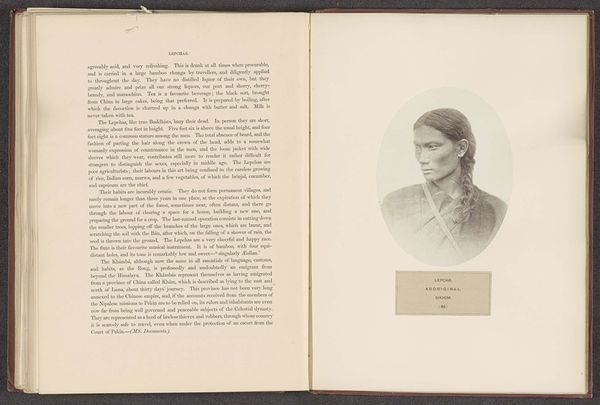

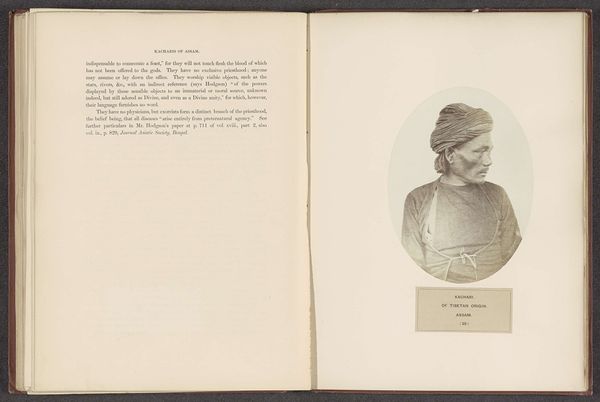

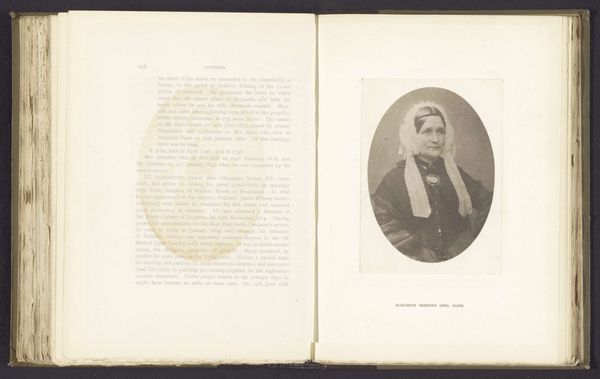

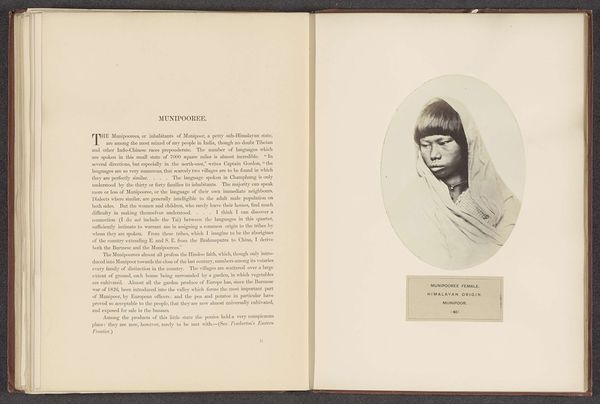

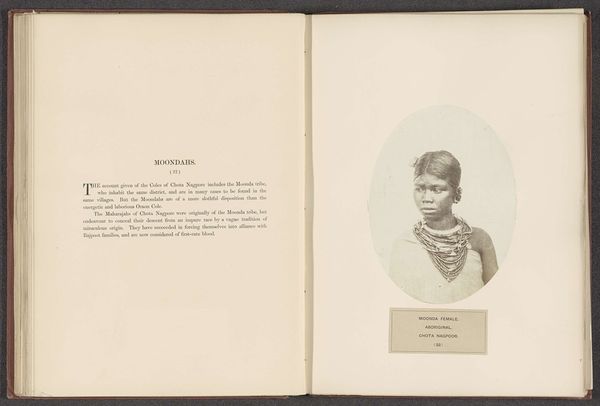

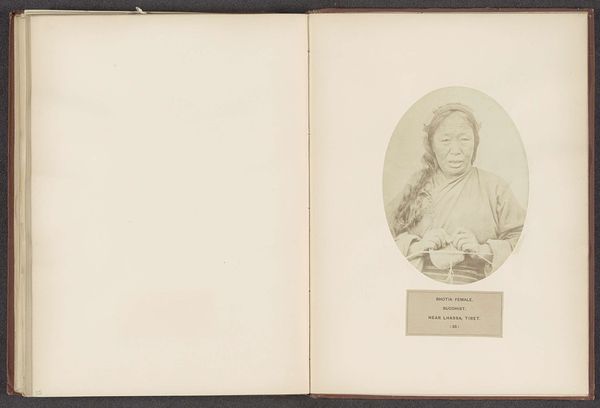

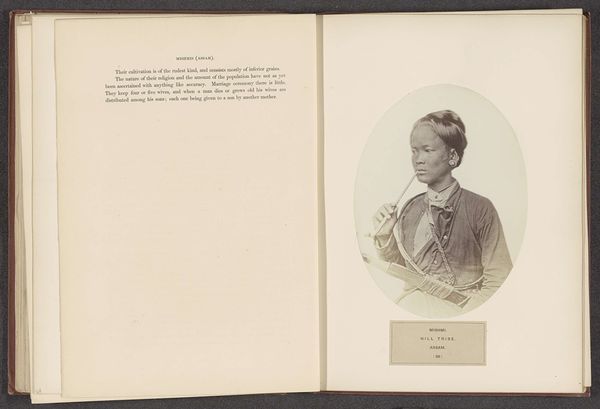

portrait

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

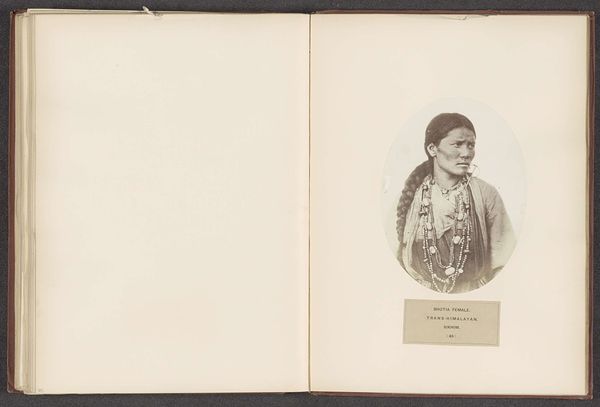

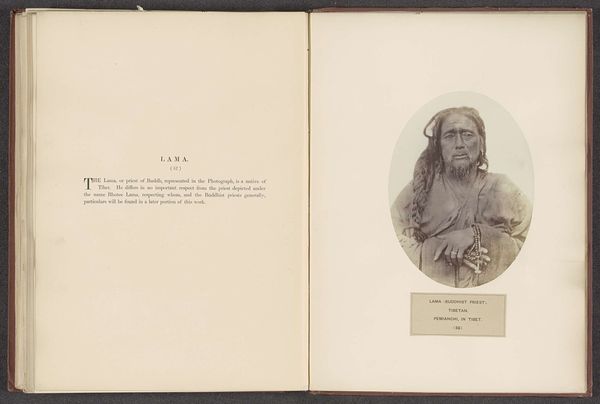

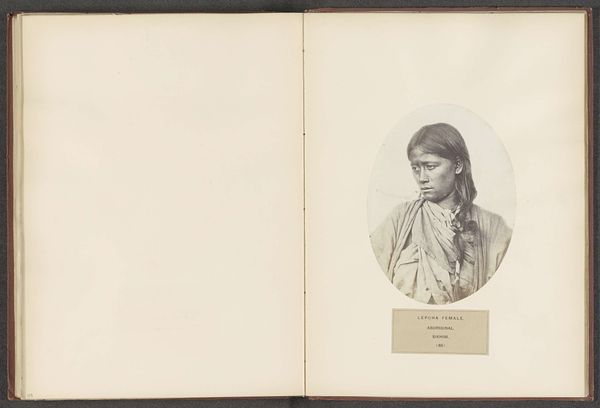

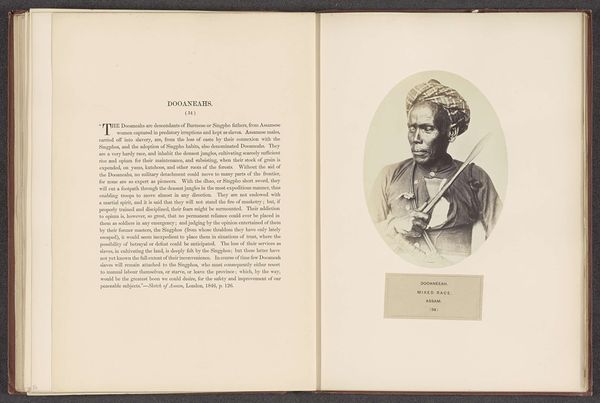

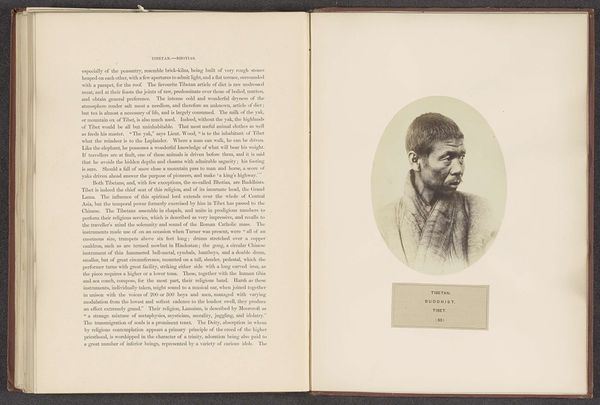

Curator: Looking at this stark, dignified image, one senses both distance and intense curiosity. What springs to your mind? Editor: He looks stoic. Reserved. And there’s a shadow there, in the image itself but also on him, that feels loaded. Is that about right? Curator: This portrait, an albumen print, dates from before 1868 and captures an unnamed Bhutia man from Sikkim. It’s credited to Benjamin Simpson. And you’re right; that reserved quality… these images were often part of larger anthropological surveys. There’s a whole power dynamic at play. Editor: So the “scientific” gaze turns him into an object. I see what you mean. Tell me, as an iconographer, how do you read this culturally? Curator: Well, on one level, it's tempting to dissect the necklace, the clothing… to assign symbolism based on contemporary understanding. But that might be imposing meaning rather than revealing it. What matters more, perhaps, is that Simpson, even within the constraints of his time, has captured an undeniable humanity. The sharp angles of his face suggest resilience, which is amplified by his steady gaze into the distance, while other details point toward an ethnic origin from the Himalayas that is indeed very specific. Editor: The act of documenting – almost cataloging – ethnic groups through photography like this raises a lot of questions. Where are these photographs going, and who gets to interpret these faces? The subjects surely had little to no say in it. Curator: Precisely. And that speaks to a broader issue around the public role of images like this and their power to shape perception, particularly within a colonial context. Orientalism used visual materials for social manipulation to shape perceptions of “others”. The subject becomes less a person and more an archetype. Editor: Despite it all, I am touched by the details you brought up about his gaze and the sharp angle of the face. Makes me want to read more, investigate more, and decolonize that image. Curator: I am delighted by the fact that in 2024 this is exactly what is happening. Visual materials and photographs have shaped and reshaped culture; nowadays our job as curators and investigators is to revert the course of imposed colonialist and orientalist power dynamics in these visuals, aiming for a fairer representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.