oil-paint

#

impressionism

#

oil-paint

#

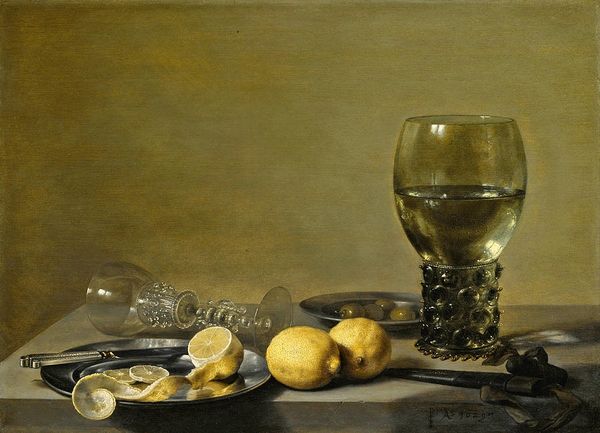

realism

Dimensions: 38 x 46 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: What strikes me first about Manet's "Oysters," painted in 1862, is how somber it feels for a still life. The color palette is muted, almost melancholic. Editor: It’s fascinating, isn't it? These objects – oysters, lemons, a small sauce boat – all presented with such starkness. Food is rarely just food, it carries so much symbolic weight, particularly in painting. Curator: Absolutely. Oysters, throughout art history, often symbolize luxury and sensuality. But here, Manet seems to subvert that. There’s a rawness, an almost unsettling quality in how he portrays them. The brushstrokes are loose, immediate, giving the impression of something very fleeting. Editor: The loose brushwork, verging on abstraction, is certainly striking, especially if we consider the context of Realism at the time. Manet is playing with representation, not quite abandoning it, but definitely pushing the boundaries. The setting is quite anonymous. No setting, the neutrality of the scene concentrates attention on the food. The austerity could also comment on shifting social norms around luxury consumption. Curator: The composition is compelling, as well. The stark contrast between the dark background and the lighter elements forces your eye to move around, connecting these disparate elements – the piled oysters, the cut lemon, the utilitarian fork. It's like a meditation on modern life. What's on our plate? Editor: It could easily spark debate around concepts of taste, access, and the politics of what we choose to depict. The scale of the work, relatively small, contributes to the sense of intimacy. This isn’t a grand, celebratory banquet scene; it's a more private, contemplative moment. It gives a feeling that he wanted us to think of that intimate circle that gets access to fresh seafood, which, back in 1862, would definitely still mean wealth. Curator: A final thought: consider how Manet, a painter known for his figure studies, renders these oysters almost as portraits themselves. Each one, unique and subtly shaded, invites a sort of strange empathy. They're not just things; they're relics. Editor: An invitation, perhaps, to consider the world through the specific, material details. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.