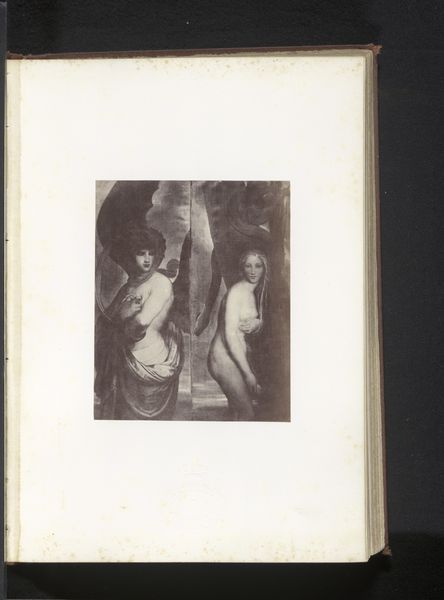

Reproductie van een schilderij van een portret van Marie Anne de Mailly-Nesle door Jean-Marc Nattier before 1873

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a reproduction, a print on paper, made before 1873 of a portrait of Marie Anne de Mailly-Nesle by Jean-Marc Nattier. It’s a somber image, isn’t it? It feels very restrained, almost formal. What's your take? Curator: Restrained is an interesting word. I’d argue that even in reproduction, the Rococo style aims to project status and dynastic power. Marie Anne de Mailly-Nesle was, after all, a mistress of Louis XV. Doesn't knowing that shift how we understand this image and its public function? Editor: It definitely does! It goes from just a formal portrait to a symbol of power, a statement about her position in the French court. How were portraits like this circulated and viewed at the time? Curator: Prints like these were essential in shaping public perception and disseminating images of the powerful. Think of it as early social media. It allowed those outside the immediate court circle to see, and therefore acknowledge, the status of figures like Madame de Mailly. And who commissioned or disseminated the print significantly impacts our interpretation of this image, right? Editor: So the choice to reproduce *this* painting was in itself a political act, emphasizing a particular kind of power and influence. Was there any discourse on whether it should have been public for the consumption of everyday people? Curator: Exactly! Now, think about who had access to these prints. Were they readily available to the masses or primarily circulated among the upper classes? The answer affects how we understand the print's role in reinforcing social hierarchies. It begs questions, such as, what happens when images of excess are broadly circulated during periods of revolution? Editor: That really brings the historical context to life. Seeing it as a carefully constructed piece of propaganda rather than just a pretty portrait completely changes the meaning. I hadn't thought about it that way at all. Curator: Precisely! It's never just a pretty portrait. Examining the conditions of its production and consumption unlocks so much about the society that created it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.