drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

realism

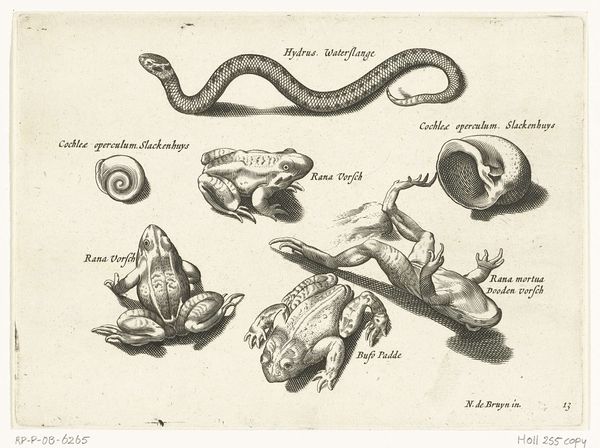

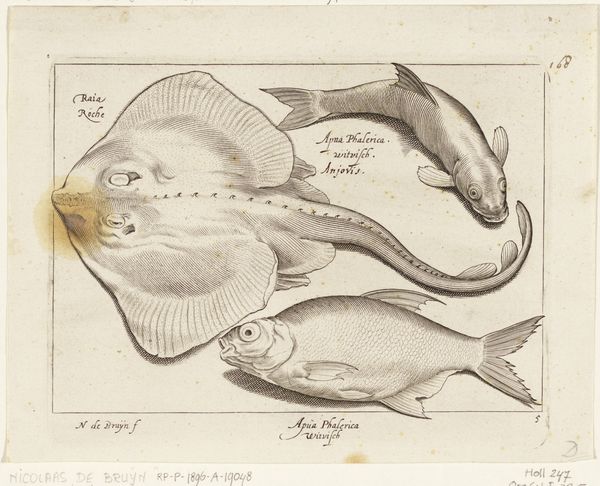

Dimensions: height 125 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s delve into this fascinating print, "Waterslang, kikkers en padden," which translates to "Watersnake, frogs and toads." Created by Nicolaes de Bruyn sometime between 1581 and 1656, it’s currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It uses ink to realize its realistic, scientifically charged topic. Editor: Ugh, okay, my first impression? It feels like stepping into a 17th-century biology class—in a Tim Burton movie. A slightly morbid one, I might add! Look at that poor frog on its back; what’s that about? Curator: The print embodies the burgeoning interest in natural history during the Renaissance and early modern period. De Bruyn, through his rendering of these amphibians and the snake, participates in an artistic project of classifying and documenting the natural world. But, beyond classification, it brings us to the societal obsession with scientific observation in the early modern period. The details! The careful lines of the shell. All these components can serve as important documents. Editor: Yes, those details. The texture of the frog skin is impressive, the scales on the snake too. And, honestly, this could be a great tattoo design! The careful arrangement of these creatures on the page gives the whole image this odd feeling—a bit sterile and yet lively, right? Almost as if it’s a specimen display, pinned for all to see. But is that a commentary? Curator: Possibly. This kind of work contributes to understanding the relationship between humanity and nature. How were animals viewed, understood, and what anxieties are inherent to representations of living things? Consider that the depiction of "lower" creatures was often deployed to reflect ideas about the social order. Editor: So, we see art serving ideology even in a seemingly neutral scientific illustration? I guess no image exists in a vacuum, does it? This brings me back to that one poor amphibian—does it signal morality to you? It makes me wonder whether, beyond objective classification, these choices reflected prevailing moral views and fears of this era. Curator: Exactly! These illustrations contribute to a bigger picture of societal, gendered, and political understandings of early modern period. Each small animal can carry great meanings and anxieties about social life. Editor: Well, it’s fascinating how something that looks like it's just about cute swamp creatures is layered with so many possibilities. I'll definitely remember this; it has so much context swirling beneath it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.