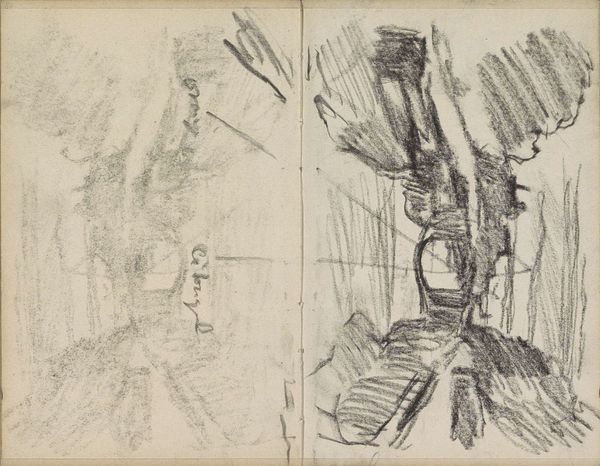

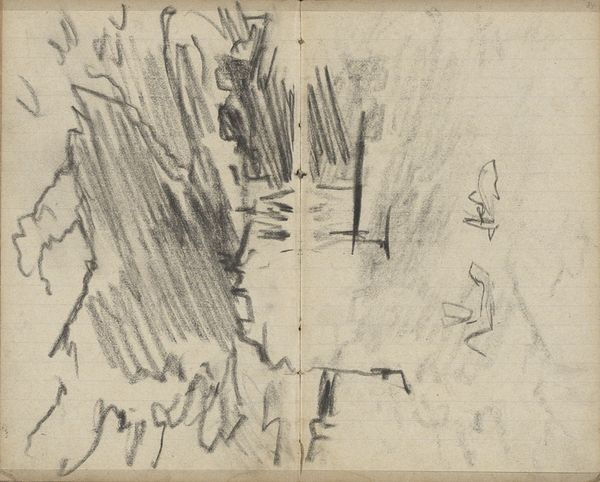

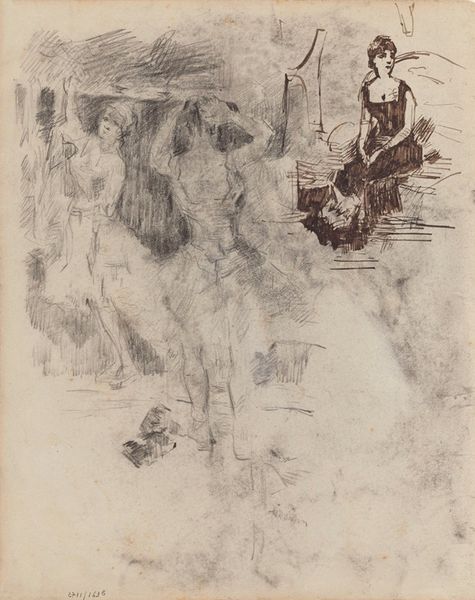

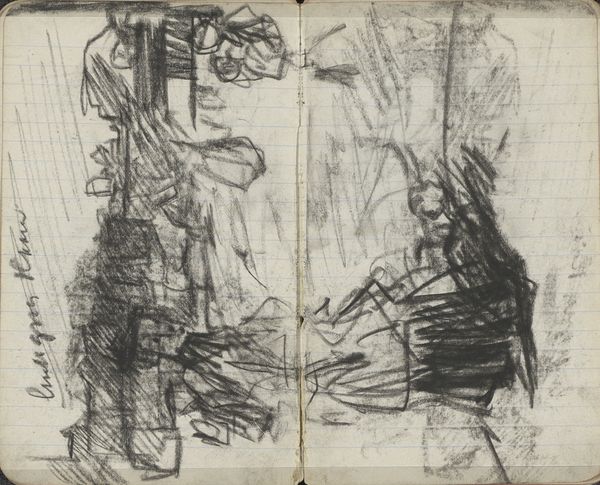

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

impressionism

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

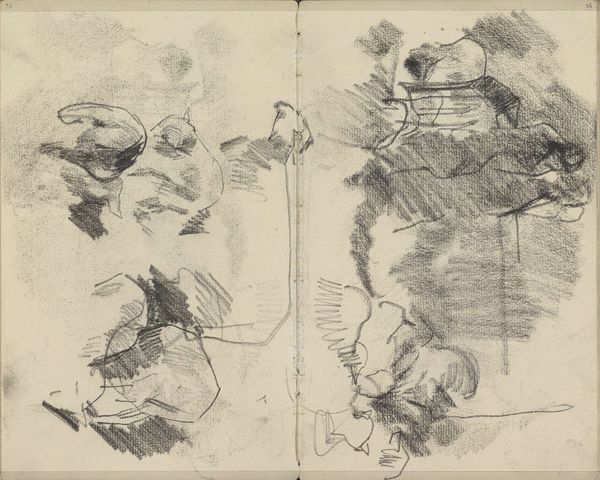

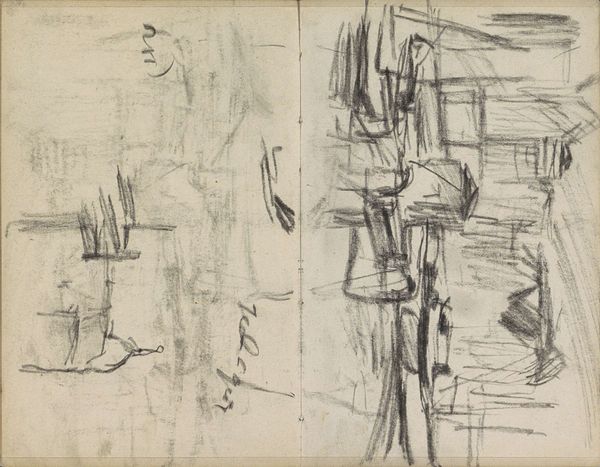

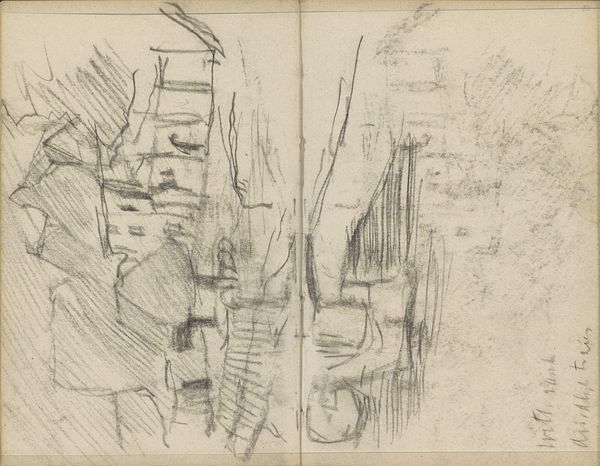

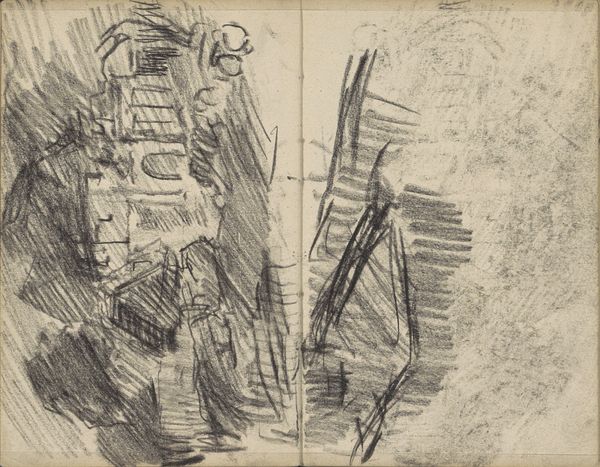

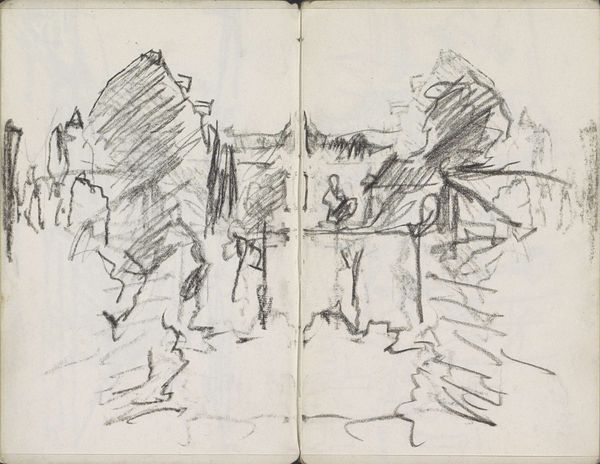

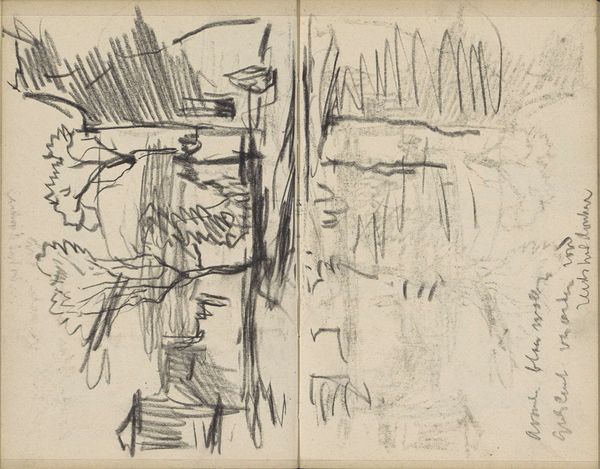

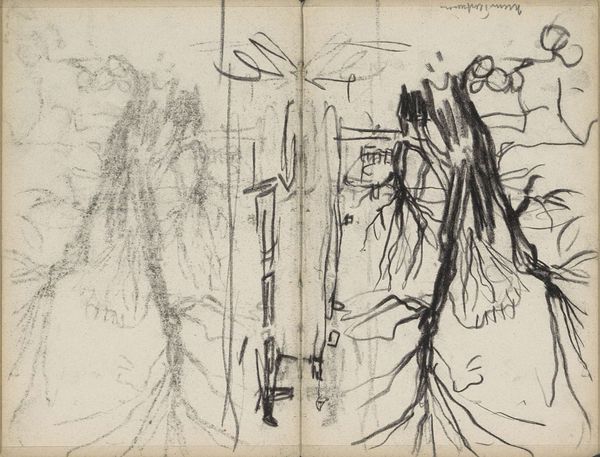

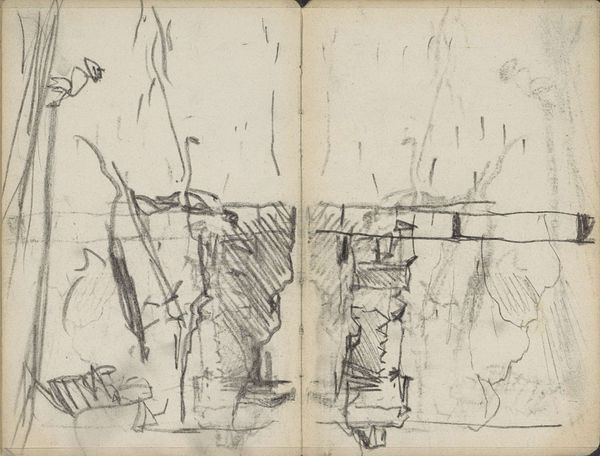

Curator: Immediately, I notice a somber and somewhat melancholic feel. The composition seems to draw us in with stark contrasts in shading and detail. Editor: We're looking at "Studie, mogelijk van een duinlandschap," or "Study, possibly of a Dune Landscape," by George Hendrik Breitner, made between 1880 and 1882. It’s a pencil drawing, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. As a sketch, it invites examination into the conditions of its making; a private moment by the hand of the artist using humble, easily obtained tools, and resulting in what we see now. Curator: Yes, a landscape emerges slowly as we really look at this; the textural variance achieved just through the graphite is quite beautiful, moving from broad soft applications of the pencil on the left page, to intense hatching on the right page where we clearly see details of either dunes or the undergrowth found on those dunes. One thinks of the long hours that may have gone into rendering those fine lines. Editor: Precisely, Breitner positions himself, and therefore us, in relation to the landscape. What does the landscape represent at that time? This was a period of rapid industrialization in the Netherlands. Landscapes came to symbolize the untainted idyllic, so to speak. Breitner made studies of working-class districts too. This might be thought of as his turn away from urbanity. How could the drawing itself mirror some sense of detachment? Curator: I notice Breitner really experiments with tone; from near-white to rich charcoal hues. Considering the date of the work and the social context of the late 19th century, it is also important to acknowledge the materiality. Where did his pencils come from? How were they made? And by whom? These were commodities shaped by evolving consumer cultures that helped develop distinct forms of labor and specialized commodity chains during his era. Editor: Excellent point. Breitner himself became a brand in Amsterdam, known for his raw portrayals of modern city life and bohemian personality. In his landscapes, though, that persona softens, as we sense an engagement with questions about labor, class and social value. Who would’ve been given access to those dunes? Who would have been excluded, by law, custom, or unspoken agreements of segregation? Curator: Absolutely; those considerations provide a much wider interpretation, a reminder that no work of art exists in isolation. I can see his emotionality at work through what his hands were doing with accessible media. Editor: A necessary perspective—by focusing on context and materiality, we tease out these silent, unspoken questions. Thanks for highlighting how material is intertwined with these bigger questions, so key for modernizing Amsterdam and, really, everywhere.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.