painting, print, textile, watercolor, sculpture

#

painting

# print

#

textile

#

flower

#

watercolor

#

sculpture

#

watercolour illustration

#

decorative-art

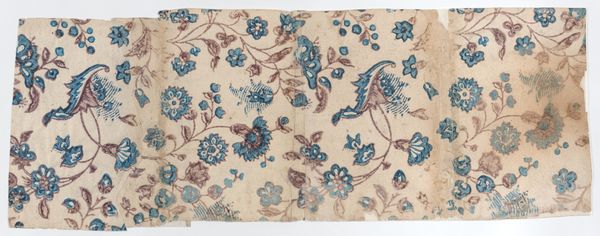

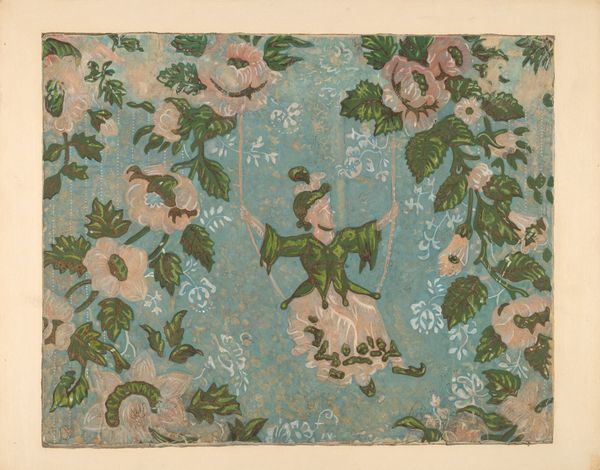

Dimensions: L. 17 1/2 x W. 35 inches 44.5 x 88.9 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We're looking at a textile work called "Piece," likely made between 1830 and 1835 by Bannister Hall. It's currently held at the Met. I’m immediately struck by how this pattern, although floral and seemingly innocent, feels so formally arranged and almost... oppressive. How do you interpret this work, especially considering its historical context? Curator: It’s insightful to pick up on that sense of formality, even oppression. We have to remember that textiles like this weren’t just decorative. They were deeply embedded in the social and economic structures of the time. The detailed floral patterns represent a specific aesthetic tied to class and status. How might the labor involved in producing such intricate designs relate to the experiences of women, particularly those from marginalized communities? Editor: So, the beauty masks a potentially exploitative process? It makes me wonder who was consuming these textiles and who was creating them. Curator: Exactly. These fabrics were often used within domestic spaces, constructing an ideal of feminine virtue and domesticity. However, the production of these very items often relied on the exploitation of women, both in Europe and, through the cotton trade, enslaved women in the Americas. The “innocent” flowers take on a whole different meaning when viewed through that lens, don't they? The swirls and curves might represent control, and manufactured status. Editor: Definitely. It completely reframes how I see the piece. I was initially just reacting to the pattern itself, but now I'm thinking about the human cost and the power dynamics woven into it, almost literally. Curator: It’s a powerful example of how even seemingly decorative objects can be sites of complex and often uncomfortable historical narratives. The study of decorative art helps us engage in political dialogues on labor, class, gender, and race. Editor: This has shown me how important it is to look beyond the surface of an artwork and consider its connection to broader historical and social realities. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.