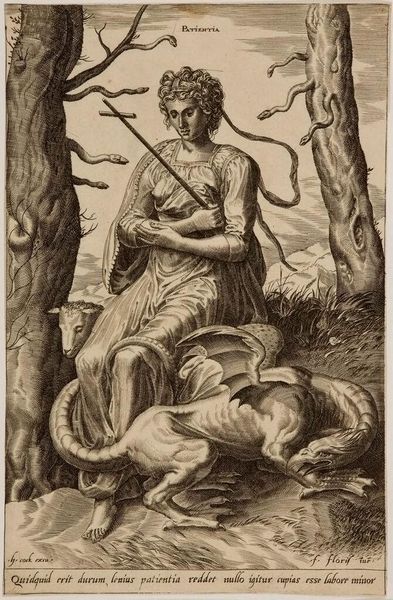

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

winter

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 274 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Cornelis Cort brings us "Pales," an engraving dating from sometime between 1724 and 1751, here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first thoughts? Editor: It has a very somber mood to it. Despite the classical influences, something about the rendering feels very grounded, like this is less about idealized forms and more about the toil of earthly survival. Curator: That sense of toil is fascinating in relation to the goddess Pales. This piece participates in a larger tradition of allegorical depictions, presenting her as an embodiment of winter. I find the tension compelling – she is, simultaneously, a powerful deity and someone vulnerable to socio-economic conditions. Editor: The wheat woven into her hat, the drowsy bull, even the agricultural tools beside her...these details really anchor the piece symbolically. Wheat suggests harvest but also perhaps a hope for future bounty, even in winter. Curator: Precisely. And consider where it was made; understanding Dutch society at the time sheds further light on how identity and agricultural prosperity intertwined. It suggests the complex ways resources and gender dynamics intersected within farming communities. Editor: It’s interesting how the landscape in the background, despite its small scale, speaks volumes. The depiction of snowy mountains, as seen from what looks like a barn, really plays into the theme. Winter is literally hanging over her world. It's potent. Curator: And she, in turn, seems resigned, rather than celebratory. It almost undermines conventional interpretations of divinity, prompting considerations of labour beyond class-based limitations. What is she beyond "the deity," if she is forced to hold her own tools? Editor: This piece leaves a lingering unease, doesn't it? There is strength on display, yes, but an underlying struggle for resources that continues today. Curator: Agreed. Its power is precisely rooted in how it compels a critical examination of what it means to perform divinity, not merely be divine. Editor: That interplay of burden and icon—definitely a lot to ponder.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.