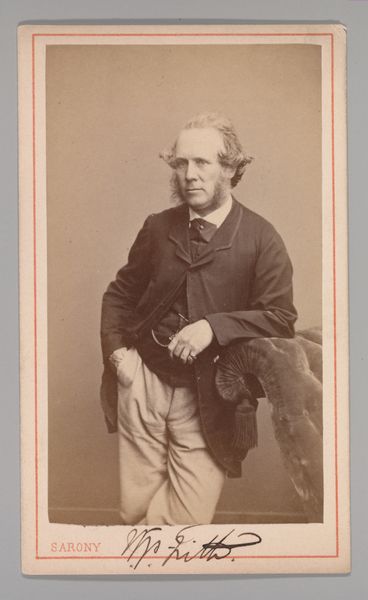

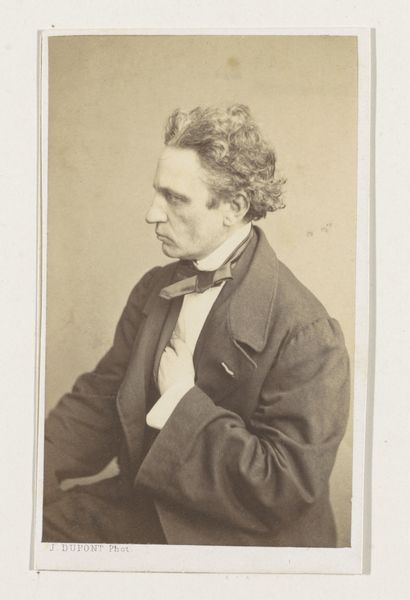

![[Henry Weekes] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzA1YTYyMGE5LTc2MDUtNDE2OC04ZTMyLTg4M2IzOWU5ZmIzOS8wNWE2MjBhOS03NjA1LTQxNjgtOGUzMi04ODNiMzllOWZiMzlfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

men

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

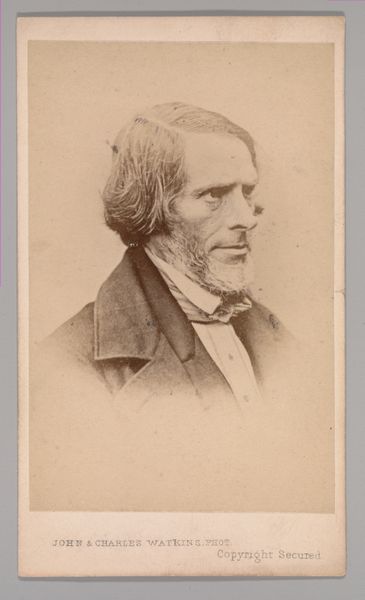

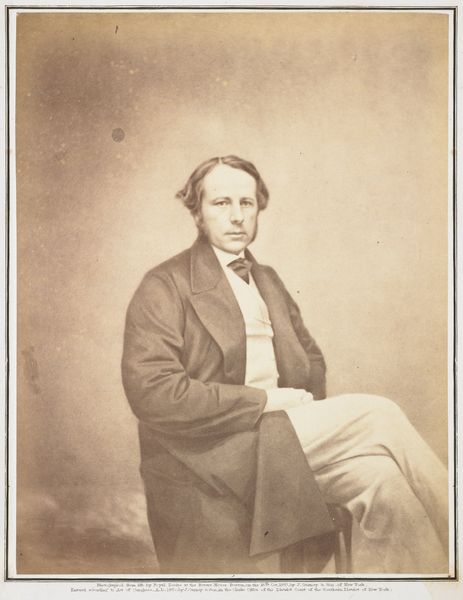

Curator: We're looking at a gelatin silver print portrait taken in the 1860s by John and Charles Watkins, titled “[Henry Weekes]”. It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It's rather striking, in a subdued way. The tones are sepia, verging on monochrome. What I immediately notice is how sharply the figure is set off against that neutral ground, that’s almost blurred. A man of obvious status conveyed via photographic technology. Curator: Precisely. Note how the subdued palette and meticulous gradation create depth. Observe the careful orchestration of light and shadow that molds his features. Semiotically, the controlled tonality whispers of a deliberate restraint characteristic of that era's aesthetic values. Editor: Of course, portraiture at this time played a vital role in shaping social identity, especially with photography becoming more accessible. It democratized the genre in some ways but also reinforced class distinctions; think about who could afford these photographic sittings, and how it was meant to project their stature. Curator: An important observation! Furthermore, we can analyze the composition's structural elements. The sharp contrast defining his contours contributes significantly to its overall presence. The framing further emphasizes his head and shoulders, commanding our attention while subtly hinting at professional achievement and seriousness. Editor: This really highlights how these images, initially considered tools for documentary accuracy, were already carefully constructed performances of the self, right? And the fact it's now in the Met speaks volumes, doesn't it? Shifting from simple documentation to cultural artifact. Curator: It does indeed. By engaging in close formal reading, we glean not just an image of Weekes, but a distilled visual text pregnant with symbolic significance. It represents not just individuality but also societal norms filtered through technical artistic processes. Editor: Absolutely. And thinking about what photography meant in the 1860s really puts a different spin on today's digital selfies. One took skill and resources and projected the values of the establishment while the other captures unfiltered self-expression. Fascinating contrast! Curator: Agreed. It is intriguing how dissecting formal elements allows understanding how it participates in broader discourses, and how photographs, beyond mere images, can be windows onto the construction of history. Editor: These subtle details underscore that art appreciation extends far beyond the simple "looking", unveiling cultural layers embedded deep inside such ostensibly conventional portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.