photography

#

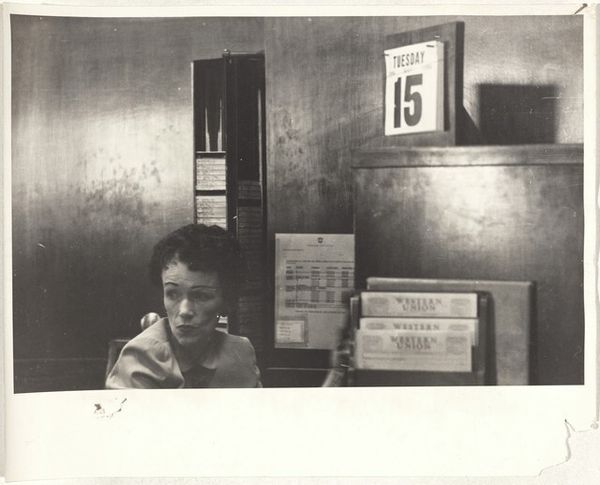

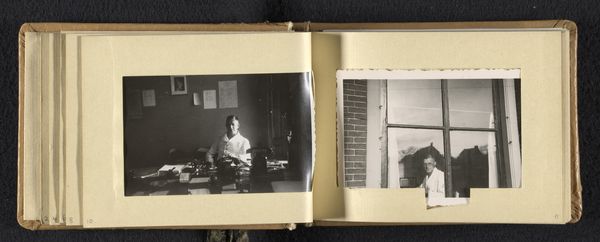

portrait

#

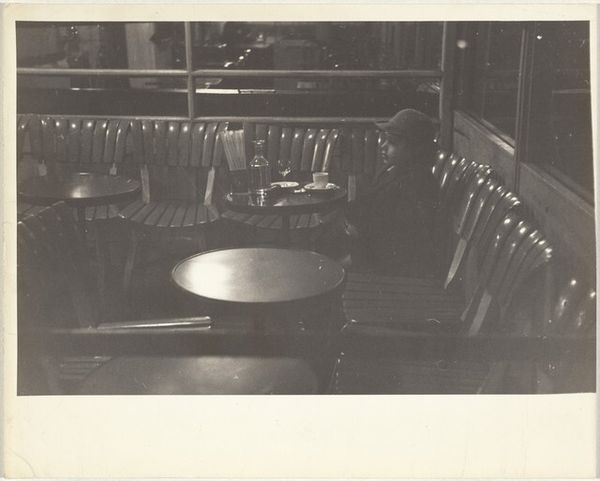

still-life-photography

#

muted colour palette

#

sculpture

#

photography

#

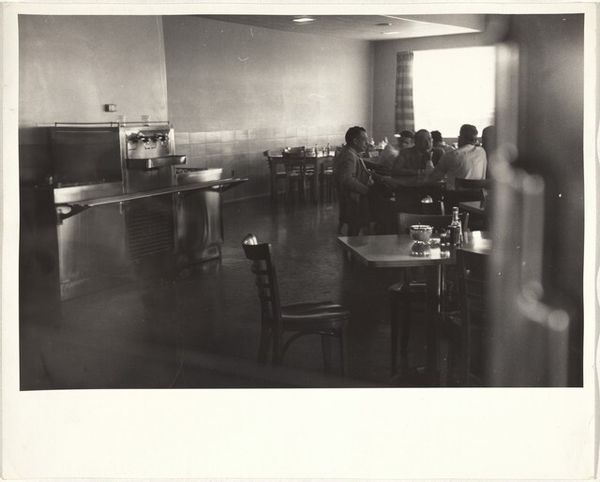

group-portraits

#

orientalism

#

muted colour

#

genre-painting

#

realism

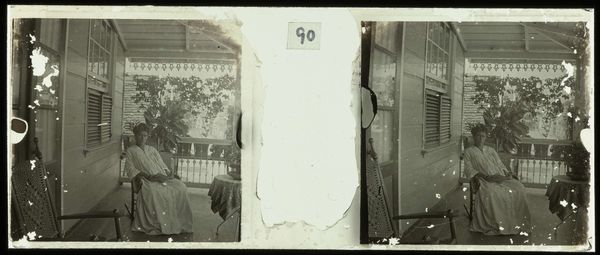

Dimensions: height 4.5 cm, width 10.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Theodoor Brouwers’ photograph, "Familie op veranda in Paramaribo," was taken sometime between 1913 and 1930 and now resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It captures a family group posed on a porch in what appears to be a carefully constructed tableau. Editor: The arrangement is quite interesting, almost staged in its formality. The subdued palette and sharp contrasts give the composition a dramatic feel, although somewhat restrained. The subdued grays and blacks give it a somewhat haunted feeling. Curator: Indeed. Brouwers’ photograph functions both as portraiture and as a historical record of the social landscape of Paramaribo at the time. This speaks to the role photography played in documenting social identities and class distinctions in the colonial context, influencing broader social imaginaries. Editor: From a purely compositional viewpoint, note how the repeating geometric shapes—the slats of the blinds, the patterned porch ceiling, even the way the figures are arranged—creates a satisfying visual rhythm, especially considering it's an asymmetrical composition. And the bright outfits serve to pop from their muted environments. Curator: Considering this rhythm, note also the clothing, presumably constructed using local labor, given that textiles at the time held a vital place in Surinamese culture and commerce. The women's choice to be clad in a specific type of fabric, crafted by specific laborers in their specific economic milieu, offers subtle clues to their socio-economic status and cultural affiliations. The objects in the foreground could also give us a peek into their consumer habits. Editor: The subtle use of light is also masterfully done, even by today’s standards. The diffused light filtering through the veranda creates a soft, enveloping atmosphere, focusing attention on the subtle gradations of tone and texture within the scene. Curator: Precisely! Looking at this from a post-colonial perspective and its materials, it prompts us to consider the photograph not just as an aesthetic object but as an artifact embedded within a complex web of social, economic, and historical relations that shaped the colonial experience in Paramaribo. Editor: It's remarkable how such a simple scene becomes so densely packed with potential analyses! It almost becomes sculptural as a function of lighting, tones, and shading that evoke three-dimensional forms. Curator: Indeed! Thinking of Brouwers' family photograph as something beyond an isolated art object pushes us to confront the broader history. Editor: Absolutely. Viewing it, through both lenses, expands our insight!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.