carving, public-art, sculpture, architecture

#

public art

#

carving

#

public-art

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

nude

#

modernism

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

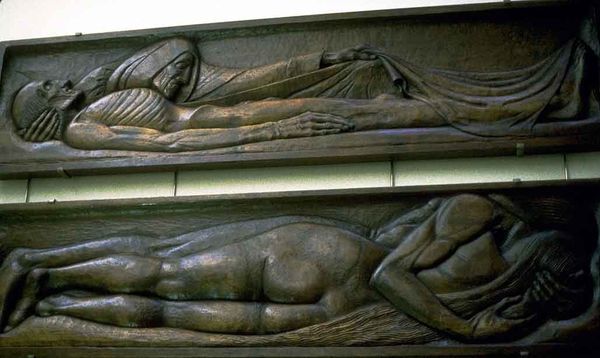

Curator: Well, here we have Eric Gill's "North Wind, St James's Park, London," dating back to 1929. It's a public art piece, a stone carving integrated into the architecture itself. Editor: It strikes me as… heavy. Monumental, certainly, but the pose of the figure, so hunched and seemingly burdened, almost makes the entire building seem to sag under an invisible weight. The stone is also rough, isn't it? Curator: Yes, and that texture speaks to Gill’s broader artistic and social vision. Gill was deeply involved in the Arts and Crafts movement and his work, though modern, often evokes a sense of medieval craftsmanship. It’s meant to emphasize the value of handwork and a kind of pre-industrial aesthetic ideal amidst rising modernity. This contrasted with mass production. Editor: And you see that echoed in the figure itself, I suppose? The deliberate roughness, the avoidance of purely polished perfection... Is there something about the way that the figure emerges directly out of the wall, solid block on which she rests? Curator: Absolutely. He’s drawing our attention to the materiality of the work. We must remember Gill saw the making of art as deeply connected to his religious beliefs and the act of creation, almost a divine labor. Plus, given its location on a public building, its role is to elevate civic space and remind the public of enduring values. Editor: Interesting to position it this way... I would read the sensuality of the female form, so close to that block as if pinned to it, as part of his project of imbuing the materials with a kind of eros, of life force and connection. Almost a way to insist that the built environment can itself feel, be felt, be experienced. Curator: That’s insightful. His work did often court controversy for that very tension, its spiritual aspirations clashing with, or perhaps embracing, its earthly representations. I’m interested in its role for London at the time of its construction. What was public sculpture meant to say about the image of the city in the early twentieth century? Editor: Right. Well, reflecting on the materials and that relationship between figure and architecture, I’m seeing it less as a straightforward celebration and more as a provocation of this period, its sensuality and roughness grounding this stone woman even further in an older idea. It provides some resistance to more standardized, easily consumed artistic output. Curator: I agree. A perfect distillation of Gill's complicated ethos. Editor: Yes, a complex relationship with progress, to be sure, rendered in heavy stone.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.