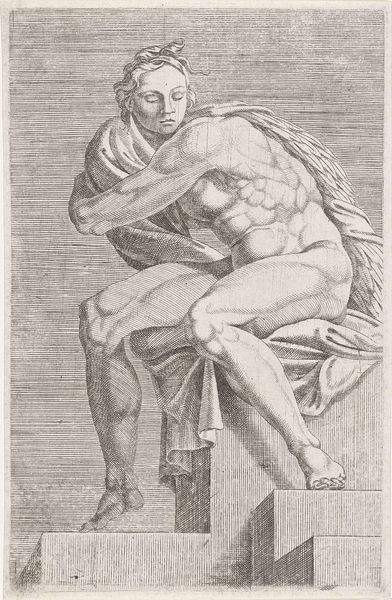

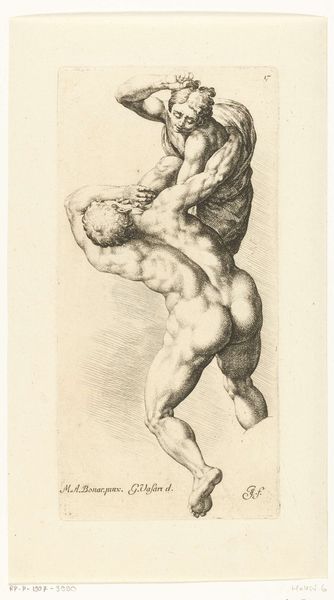

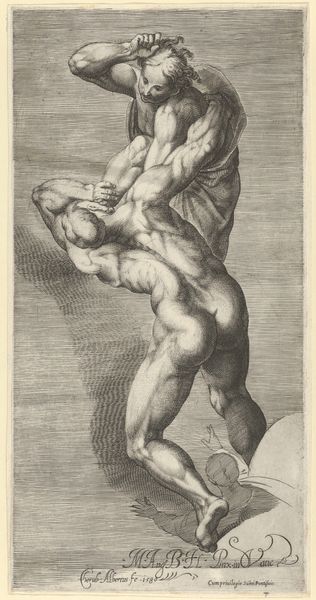

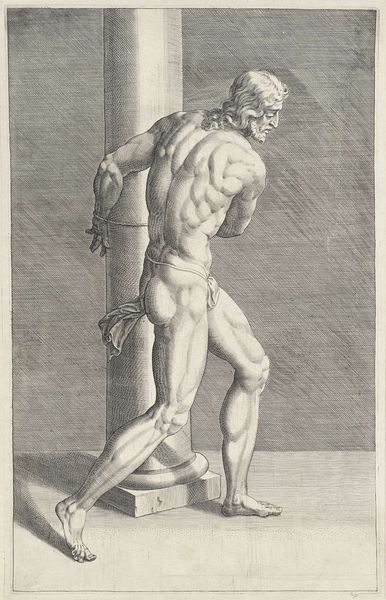

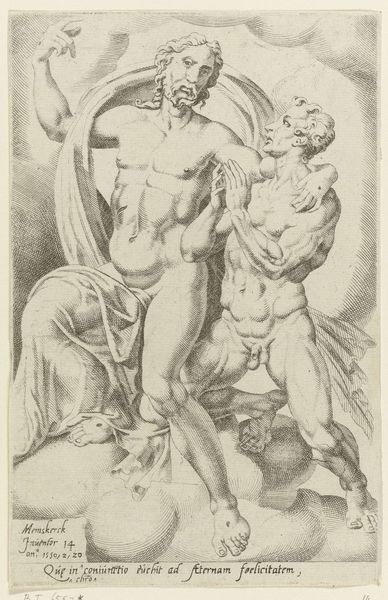

print, engraving

#

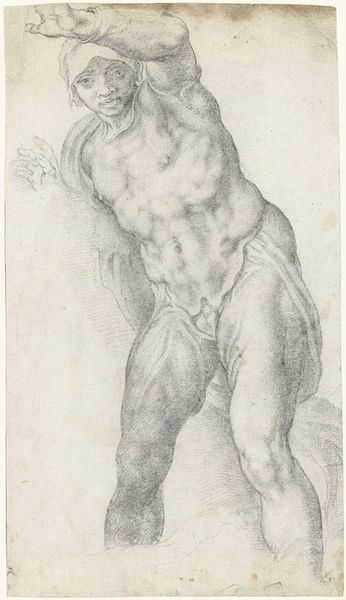

pencil drawn

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil drawing

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 216 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We are standing before Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert's "Seated Nude from the Sistine Chapel," an engraving created in 1551 and held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's a rather imposing figure. Starkly rendered, almost monumental, yet simultaneously burdened, hunched over with a veil hiding half the face. The subject matter is immediately arresting. Curator: This print offers an interesting glimpse into the artistic exchange and dissemination of ideas during the Renaissance. Coornhert never actually traveled to Rome, yet this engraving allows him—and us—to engage with Michelangelo’s famed frescoes. The print is a reflection and also an interpretation of that pivotal High Renaissance moment, and the distribution of prints like these shaped the wider public understanding of Italian art in the North. Editor: That raises some vital questions about representation and access. For those unable to journey to the Sistine Chapel, this print served as a visual proxy. But how might the artist's biases or socio-political context impact his choices in depicting this figure? Was this image used as propaganda, a means of cultural elevation, or merely artistic inspiration? Curator: I think it would be shortsighted to assign solely one of these to this kind of image. Prints were commercial objects that catered to certain expectations from its market, yet its influence over taste and promotion of Italian art cannot be understated. Moreover, the Mannerist aesthetic—the slightly elongated forms, the almost theatrical pose—were highly fashionable at the time. Editor: It also begs questions about the male gaze. Is the sitter posed heroically or objectified, and for whom? Is there perhaps an underlying exploration of the psychological or emotional experience of the subject? Also, while the muscularity could be seen as a celebration of the human form, it also risks perpetuating unrealistic ideals of the body, a concept we must also contextualize within current debates. Curator: Precisely! Coornhert’s engraving provides fertile ground for discussions about the circulation of images, the translation of artistic styles, and the role of prints in shaping cultural identity during the Renaissance. Editor: Absolutely. I walk away considering the interplay of artistic intention, socio-political context, and the viewer's own subjective experience in understanding this seemingly straightforward depiction of a figure from the Sistine Chapel.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.