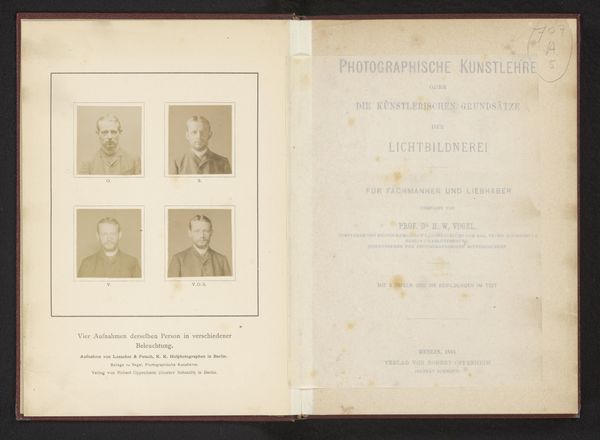

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

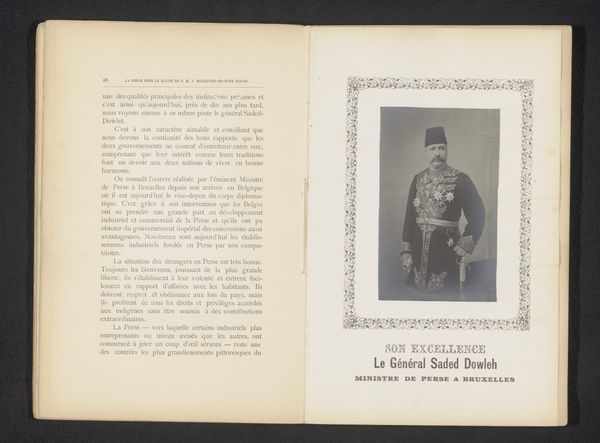

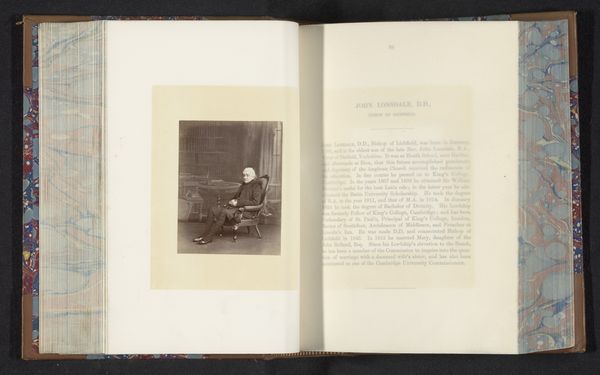

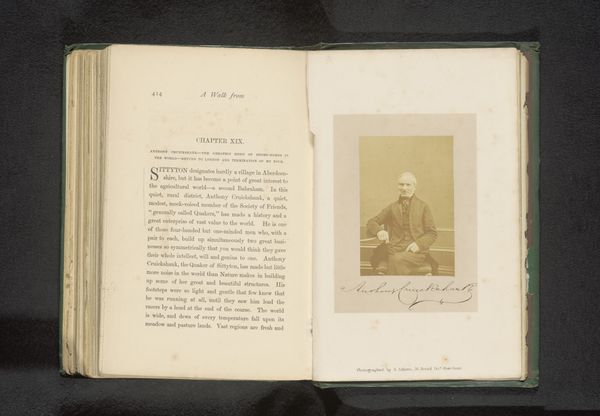

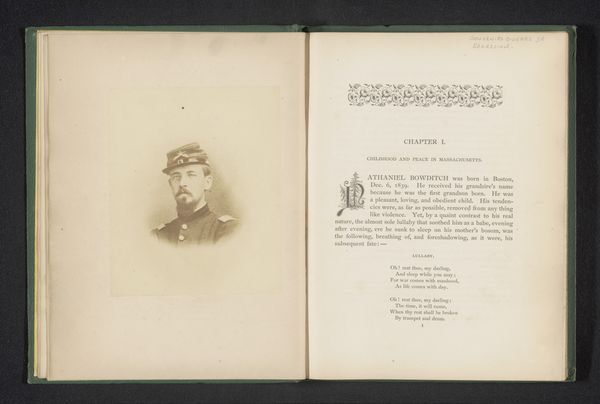

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 69 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I feel a distinct weight in the symbolism—that pith helmet is a loaded signifier. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at "Portret van Stephan Meyer met een tropenhelm," or "Portrait of Stephan Meyer with a Pith Helmet," created before 1881, likely a gelatin-silver print or albumen print. Note how the image is carefully arranged in a photograph album alongside text in German. Curator: The man's intense gaze, coupled with the exoticism implied by the helmet, stirs feelings of both adventure and... a certain degree of assumed authority. It’s an interesting blend. Is that authority earned or conferred by the cultural assumptions that pith helmet represents? Editor: Precisely. Consider the history—photography, like this print, became instrumental in constructing and reinforcing colonial narratives. This portrait is likely connected to publications about North Africa. The pith helmet, therefore, doesn't just represent travel; it evokes colonial administration, military campaigns, and an assumed position of superiority. Curator: And within that symbol lies a complex tension—the spirit of exploration mixed with a shadow of power. It reflects back a time when images played a key role in forging perceptions and power dynamics. His rather substantial beard also reads of authority. Editor: Absolutely. The portrait format itself also contributes to the feeling. He is meant to be seen as a figure of import, yet the photographic medium suggests both accuracy and the possibility of mass reproduction—which only amplifies the image’s reach and potential ideological weight. Curator: It is also very clearly posed, not a snapshot, contributing to that image-making, a deliberate constructing of self and presentation, one designed to be visually legible to a European audience. Editor: Considering how portraiture served colonial agendas, the "accuracy" becomes secondary to the values that these images were mobilized to advance. Curator: Yes, thinking about the images in albums, what stories are intentionally being written in and around these photographs, what is not being documented—what remains invisible? Editor: Exactly. This album likely sought to establish, circulate and affirm perceptions about specific geographic locations, people, and the dynamics between colonizer and colonized. Curator: Well, analyzing it, one realizes that even a simple portrait in an album can be a carrier of weighty history and ideology. Editor: Indeed. And by deconstructing these symbolic images, we better recognize their lasting effects on collective memory and cultural identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.