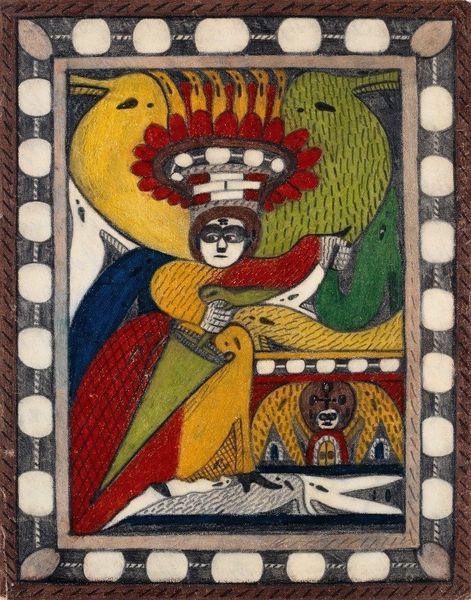

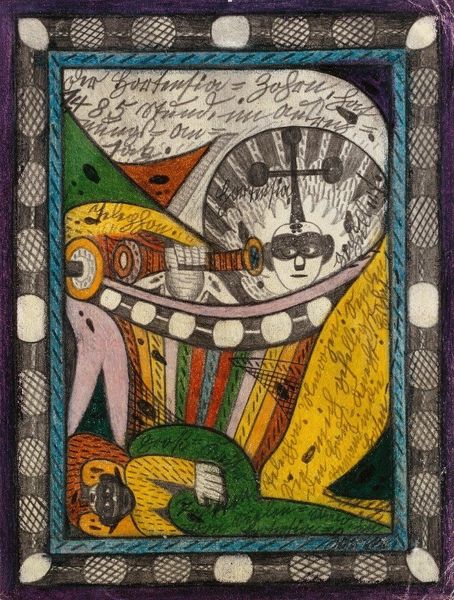

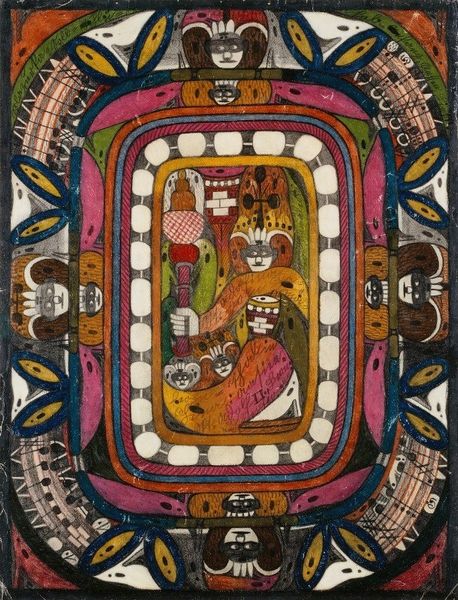

Die Kreuzigung meiner Wenigkeit, auf der Biskaya,=Haven=Insel, im stillen Ozean, im Späht=Sommer, 1,876 1920

0:00

0:00

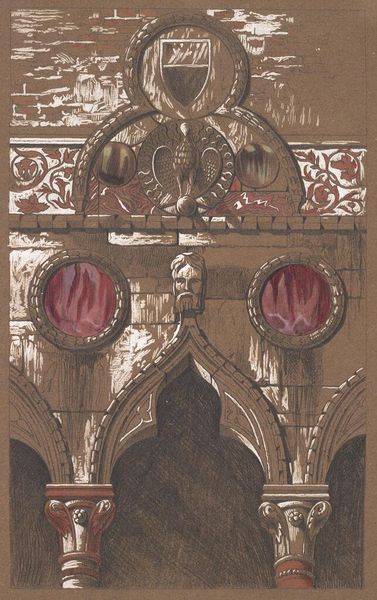

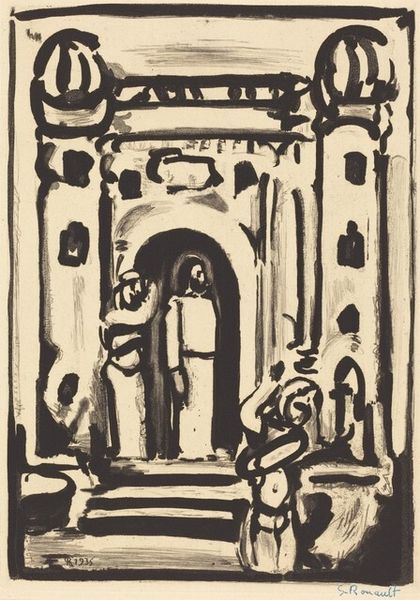

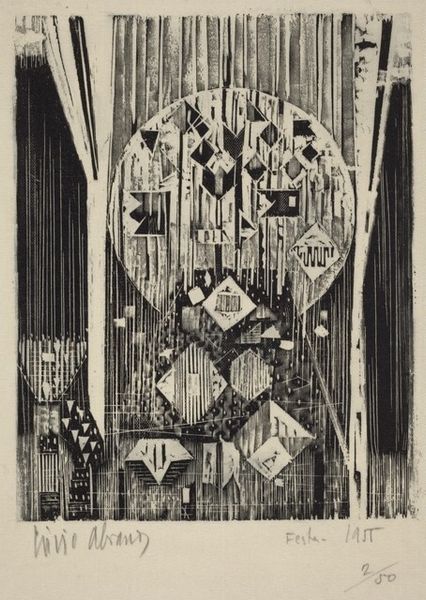

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

expressionism

#

naive art

#

pen

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

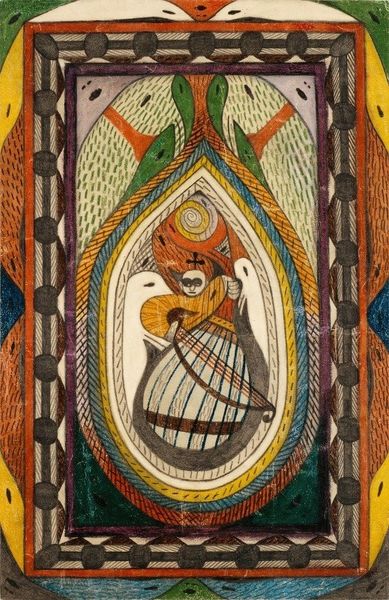

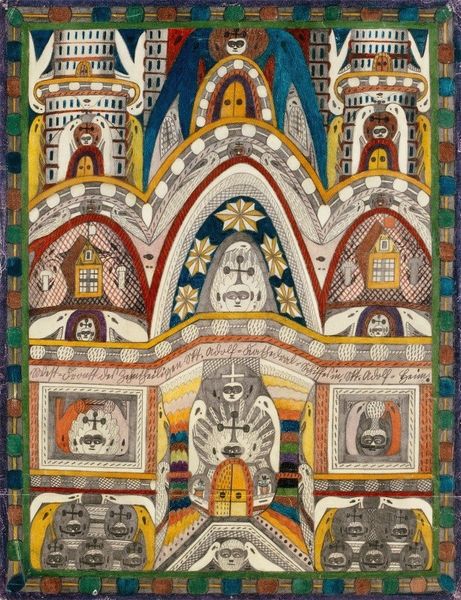

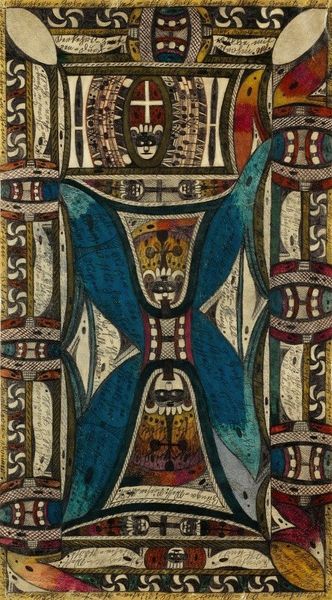

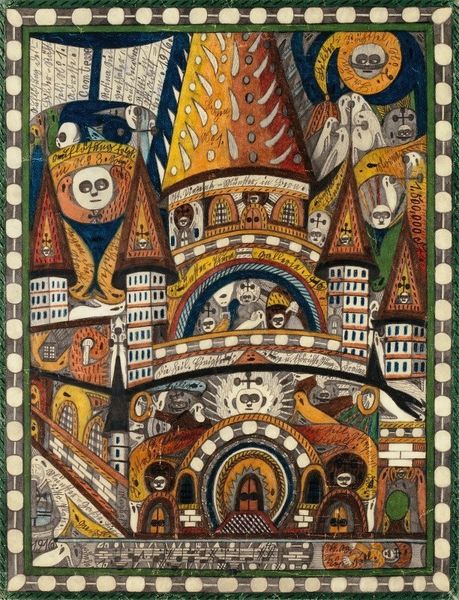

Curator: Well, what jumps out at you? I’m immediately struck by how meticulously this artist worked. Editor: Overwhelming! And claustrophobic. There's so much detail packed into every square inch. It feels less like a portrait and more like… a coded diagram. I am introduced to Adolf Wölfli’s 1920 drawing called, "Die Kreuzigung meiner Wenigkeit, auf der Biskaya,=Haven=Insel, im stillen Ozean, im Späht=Sommer, 1,876" which translated means, "The Crucifixion of Myself, on the Biscay,=Haven=Island, in the Silent Ocean, in Late=Summer, 1,876." The image uses ink, and colored pencil on paper. Curator: It absolutely functions as both! Think of it as an elaborate, autobiographical mapping. Wölfli, institutionalized for most of his adult life, creates this drawing decades after the date inscribed—1876— layering personal mythology and a reimagining of his own history into something… cosmically grand. Editor: You said mythology. The figure at the center, with arms outstretched, bound by what looks like a life preserver, he reminds me of religious iconography, but twisted somehow. Like a folk rendition of a saint. Curator: Exactly! Wölfli's entire project dances on the line between religious fervor and personal delusion. Consider the crown-like structure above his head, or the inscriptions woven throughout the background. It's all deeply personal, yes, but also plays with established visual languages of power and faith. We also have to consider Wölfli was not a trained artist. His background had little education and he was raised in orphanages after the death of his father. This type of visual presentation can also be referred to as, ‘Art Brut’. Editor: And what about the drawings, or images framed on either side of the main figure? Those appear almost like miniature versions of similar scenes but in a different context. Curator: Ah, yes, the visual echoes! These framed sections add to that feeling of layering. Wölfli often reused and reinterpreted motifs and compositions within his vast body of work. He's creating an entire, self-contained universe. Think of it as Wölfli trying to make sense of his world by meticulously archiving himself. Editor: It’s an overwhelming self-archiving that leaves me still looking for… clues? Catharsis? This one man’s need to write it all down. I still feel the heavy claustrophobia of his narrative. Curator: And it's that very intensity and meticulousness, that yearning to communicate, that makes Wölfli’s work so powerful and haunting, doesn't it? This intense desire to share a worldview constructed entirely within one's mind.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.