photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 58 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

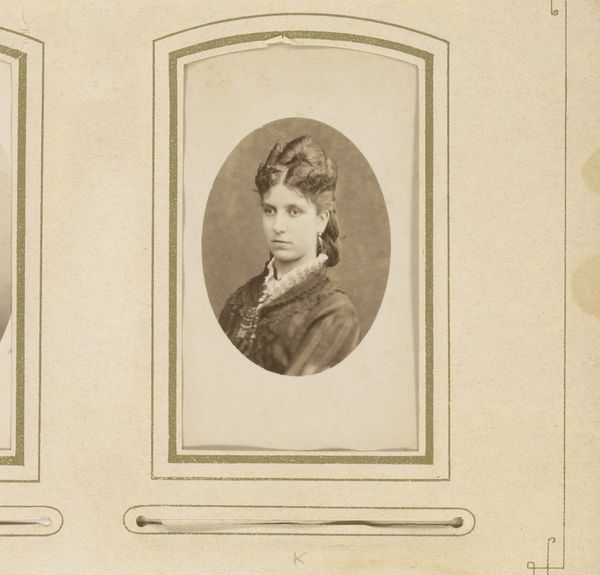

Curator: Here we have a photographic portrait believed to be of Elise Hwasser, created sometime between 1855 and 1890. It's presented as an albumen or gelatin silver print, quite common for portraits of the era. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the gentle, almost melancholy air about the woman. The soft sepia tones enhance this feeling. There is an elegance about her demeanor and that simple composition emphasizes her thoughtful gaze. Curator: I agree about the melancholic air. Think of the processes involved: the sitter, probably a working actress or associated with theater production since the woman appears to be Elise Hwasser, holding perfectly still for extended periods, exposed to harsh lighting. Consider the social conditions of studio portraiture; it's fascinating how quickly photography became integral to constructing personal and professional identities. Editor: Yes, and it also emphasizes certain aesthetics. Her hairstyle is a deliberate display, each curl placed. I wonder what structural elements hold her curls in shape. It’s almost a cascade but neatly framed, mirroring the oval that contains her image. Curator: The materiality also speaks volumes. The gelatin-silver or albumen process depended on specific supplies, chemical treatments, and skilled labor. Early photography like this was dependent on a complex global trade, and reflects the technological advancements shaping representation and communication. Editor: True, but aesthetically, notice how the light plays across her face, creating subtle shadows that sculpt her features. The framing draws the eye inexorably towards her, inviting speculation, yet reveals little beyond a quiet dignity and a certain vulnerability. Her dark eyes speak volumes. Curator: We have to think about the studio contexts that commoditized such vulnerability and elegance through formal portraiture. Who owned these images? What sort of distribution network made these photos circulate beyond family or professional networks? The social biography matters. Editor: But, equally, consider the formal interplay: the simple shapes contrasting to create a powerful whole and drawing on the artistic language. Curator: Precisely. Considering both the social function of the photograph and its inherent materiality enhances our understanding of this work and the late 19th century world. Editor: Yes, it helps unpack the photograph's power and invites us to further consider her story, captured fleetingly yet seemingly suspended forever in the frame.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.