Copyright: Public domain

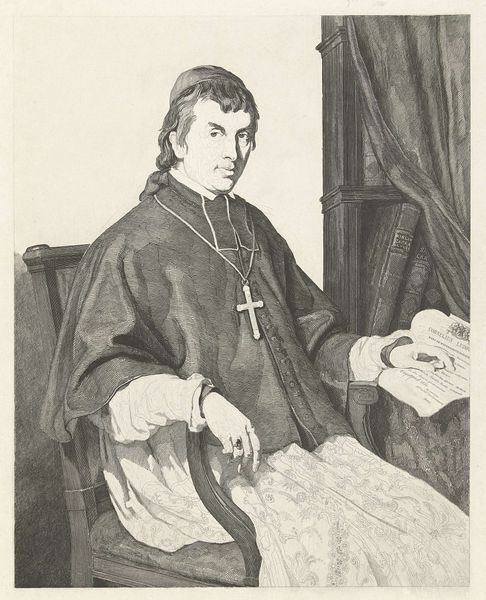

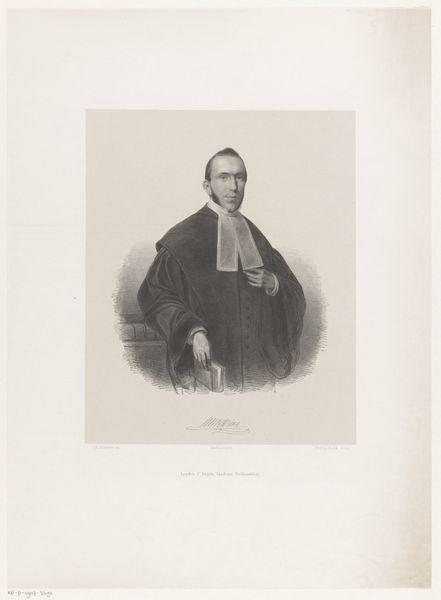

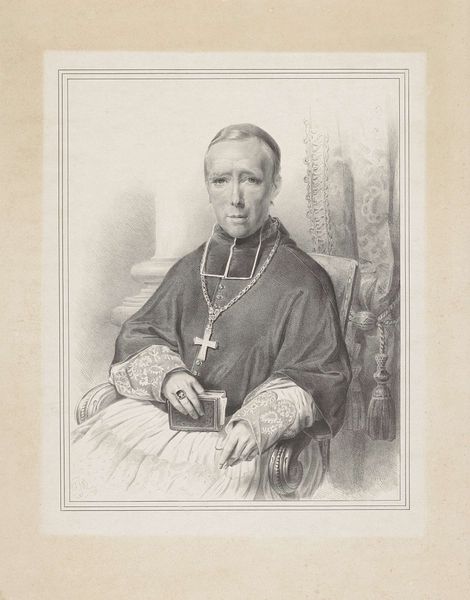

Curator: Here we have Léon Bonnat's 1889 portrait of French priest Pierre-Bienvenu Noailles. It's an oil painting. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: A study in black! And hands... I'm immediately drawn to the stark contrast of the white clerical collar against all that somber darkness. There’s a real sense of austerity. Curator: It's interesting you say "austerity," considering the opulence of the era. The piece clearly aligns with academic art and romanticism styles, evident in Bonnat’s treatment of textures, but also the context of commissioned portraiture within the Catholic Church. The cost of those pigments alone! Editor: And think of the labor, someone grinding pigments, stretching canvas... But back to the subject, his expression… He holds a tiny cross, but there's something so human, and maybe slightly sad, in his eyes. It’s far more than a simple "man of God" portrait, don't you think? Almost vulnerable? Curator: Vulnerability could also speak to Bonnat's ability to humanize a figure of considerable power. This piece provides insight into both social structures of late 19th century France and Bonnat’s skills in engaging with a wealthy patronage system. Editor: Right. He was a cog, essentially, even if a celebrated one. But seeing this image, I almost forget that—almost! The dark hues remind me of entering an old cathedral at twilight, the weight of history pressing down... a bit melodramatic, I admit. Curator: But fitting, given the sitter’s profession! The details – consider the well-worn prayer book, the placement of light to highlight the hands… The church clearly aimed to display respect and power through this commission, making a point of showing tangible, expensive artistry. Editor: So we see Noailles not just as a priest but a crafted, constructed persona within a social machine. Interesting! Makes me wonder what Bonnat truly felt about the Church. Curator: Irrelevant perhaps. It's Bonnat’s skillful use of those material resources, a church commission that now affords us an interpretation through which to unpack all that social history. Editor: Well, you’ve given me plenty to chew on. A very imposing piece. Curator: Indeed. A powerful work speaking volumes on faith, social constructs, and the means by which these images came to be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.