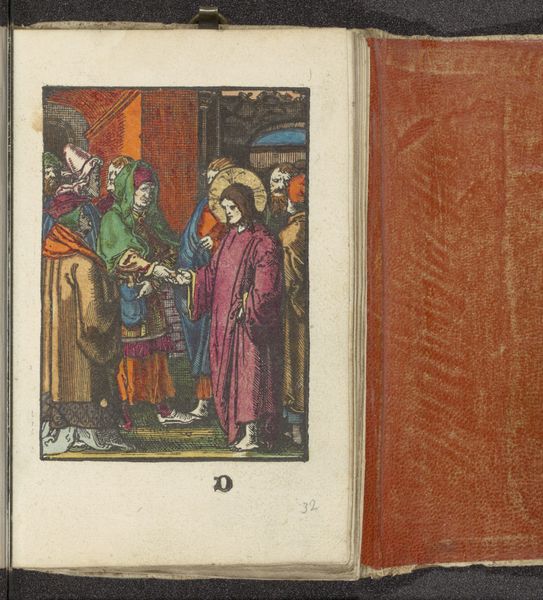

drawing, coloured-pencil, paper

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

book binding

#

coloured-pencil

#

narrative-art

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

personal sketchbook

#

journal

#

coloured pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

northern-renaissance

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 112 mm, width 79 mm, height 159 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

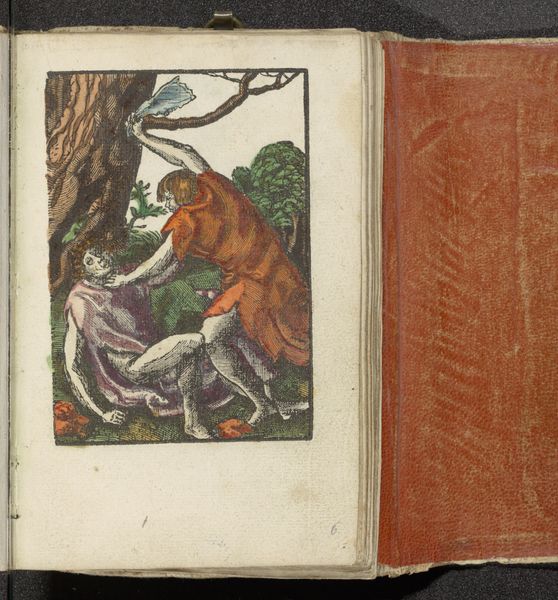

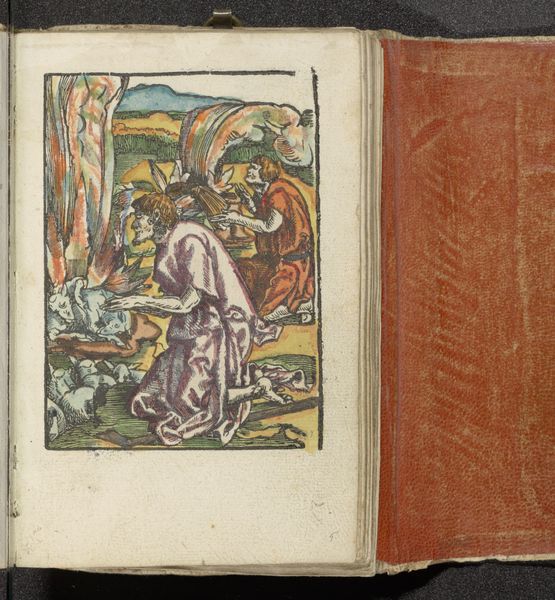

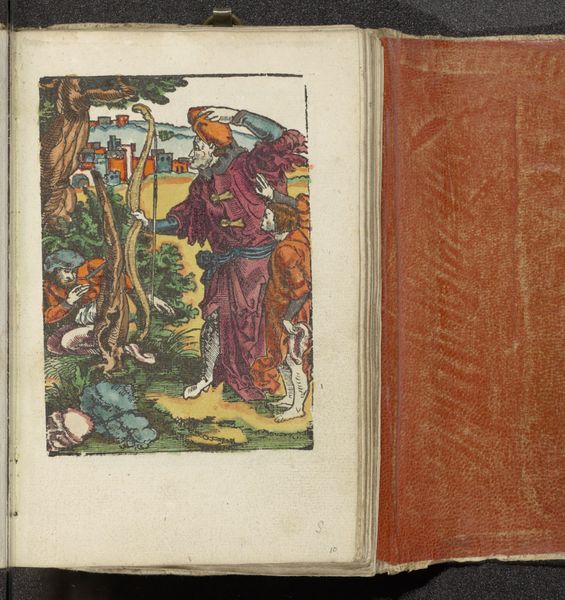

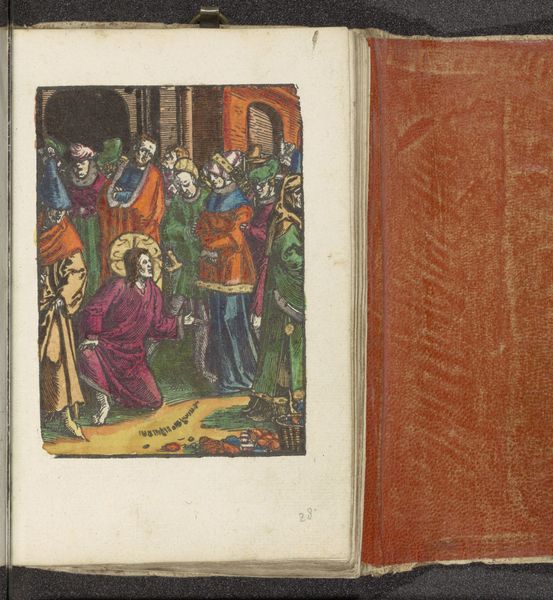

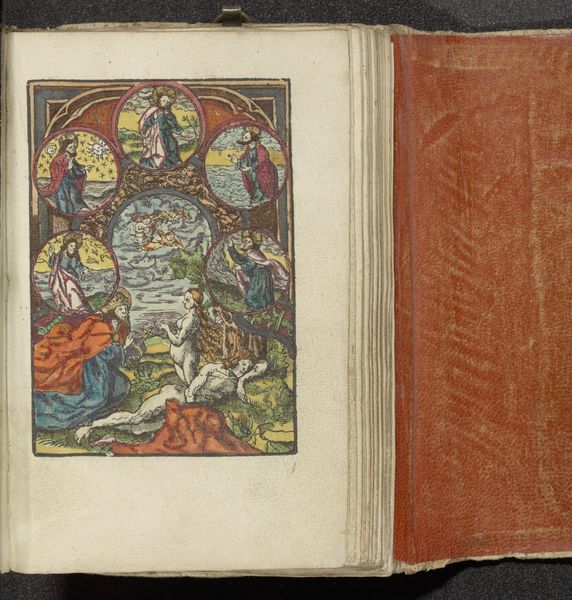

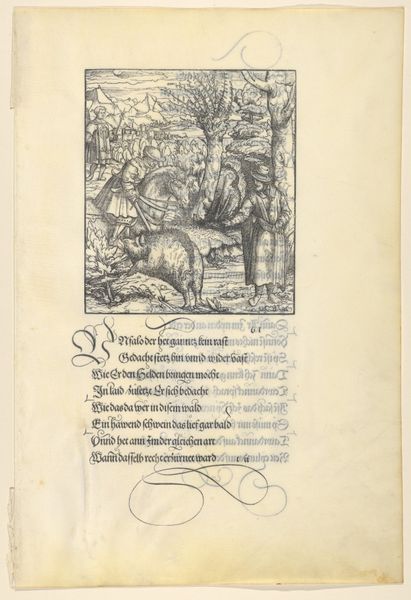

Curator: This is a drawing by Jan Wellens de Cock, "Adam and Eve Mourning the Dead Abel," created around 1530. It’s rendered in coloured pencil on paper. It looks like part of a sketchbook. Editor: It's a heartbreaking image. The grief is so palpable. There's a certain vulnerability in the figures, a departure from typical heroic depictions in art. Curator: Absolutely. Considering the time, this piece resonates with the rise of humanism during the Renaissance. De Cock depicts Adam and Eve not as symbolic figures, but as parents overwhelmed by loss, tapping into an empathetic emotional space. It mirrors societal shifts toward acknowledging individual experience, reflecting an increasingly literate, informed populace hungry for relatable stories. Editor: And the scale, being a sketchbook drawing, intensifies that sense of intimacy. It wasn't meant for grand display, but for private reflection. How does the medium – coloured pencil – inform our understanding? Curator: Well, the coloured pencil suggests accessibility, possibly a deliberate choice that breaks from the established medium used for biblical subjects. This brings into question ideas about who and what is worthy of depiction. By portraying Adam and Eve with visible signs of aging and exhaustion, de Cock democratizes their mythic status. Editor: That subverts the conventional glorification we often see in depictions of religious figures. Do you think it’s a deliberate comment on religious institutions, considering the growing critiques during the Renaissance period? Curator: Perhaps not overtly. The Northern Renaissance maintained strong ties with the Church, but it definitely presents an alternate representation that encourages personal reflection on faith, ethics, and existence itself. Also, this kind of art in sketchbooks can imply the free association and intellectual discovery artists valued. Editor: Right, that sense of questioning and inwardness feels potent, and even subversive. A quiet moment of intense human suffering depicted with raw emotion – so unlike the idealized figures common in that era. Curator: It reveals a pivotal transition in artistic and societal viewpoints during a period where individual sentiments started to be examined. De Cock effectively represents both the personal devastation felt by these iconic parents while alluding to growing debates about human representation and purpose in society. Editor: Ultimately, it’s a potent reminder of the human cost behind grand narratives, compelling us to look beyond conventional perspectives on canonical stories. Curator: It certainly is, prompting continued discussion of societal power, ethics, and representations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.