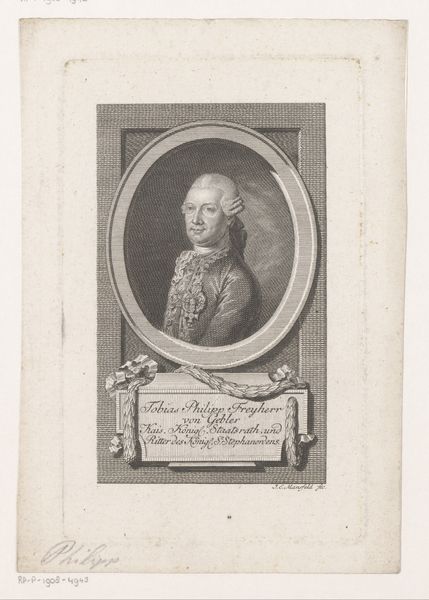

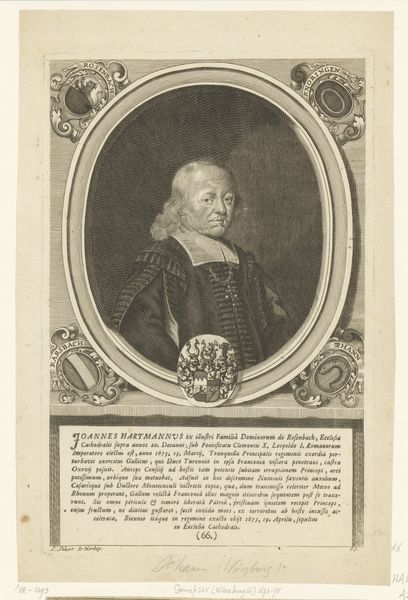

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

white palette

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 159 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this finely wrought engraving: a portrait of Carl von Mertens by Johann Ernst Mansfeld, dating from 1783. Editor: It’s quite striking, actually. There's an almost stark simplicity to the composition, the white of the paper so brilliantly set against the meticulously etched lines. That restrained palette focuses all the attention onto Mertens’ face and the subtle details of his clothing. Curator: Absolutely, and placing this within the Neoclassical movement is crucial. You see that clean aesthetic mirroring the era’s emphasis on reason and order, values instilled within its institutions and civic life. The circular frame, adorned with leaves, creates a kind of idealized presentation, placing Mertens within a pantheon of learned figures. Editor: Yes, I do see the framing serving to both elevate and contain the sitter. Look how Mansfeld uses stippling and hatching to define Mertens' features. The light catches the ruffled jabot at his chest just so, drawing the eye. But does that meticulousness lend itself to expressiveness? He looks rather…stolid. Curator: I think that reserve is quite deliberate. Portraits from this era often served to convey status and intellect. Carl von Mertens, as the inscription tells us, was a renowned doctor associated with prominent medical societies in Vienna and Paris. Editor: Precisely—it functions as an index of status. But still, note the placement of the inscription beneath the portrait like a formal base. The laurel wreath suggests achievement but contributes little to an atmosphere, I suspect. It’s controlled, measured. Curator: But isn't control itself a significant message, signaling rationalism and enlightened thinking so valued at the time? The formality reflects an effort to ground medicine within the realm of scholarly and legitimate pursuits. The arts helped with legitimization a lot. Editor: I concur, in terms of historical meaning. But for my own visual satisfaction? I find the lack of tonal variation disappointing—as beautiful as engraving can be. Curator: Ultimately, it shows the power of visual art. I like to believe it shows what was believed and how status can be both performed and created. Editor: Indeed. The print captures not only a likeness but also the aspirations of a man living in an age defined by reason and refinement—an enduring legacy in monochrome.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.