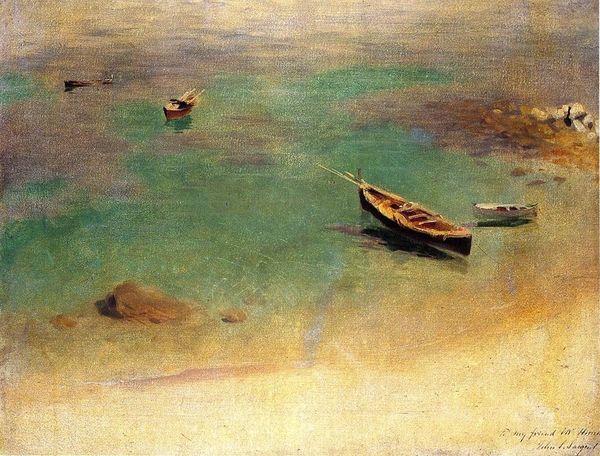

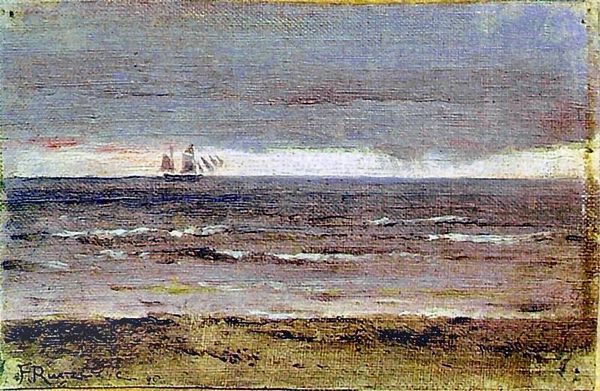

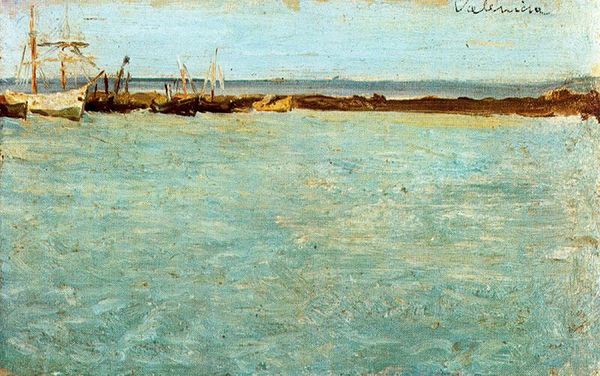

plein-air, watercolor

#

boat

#

ship

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

ocean

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

#

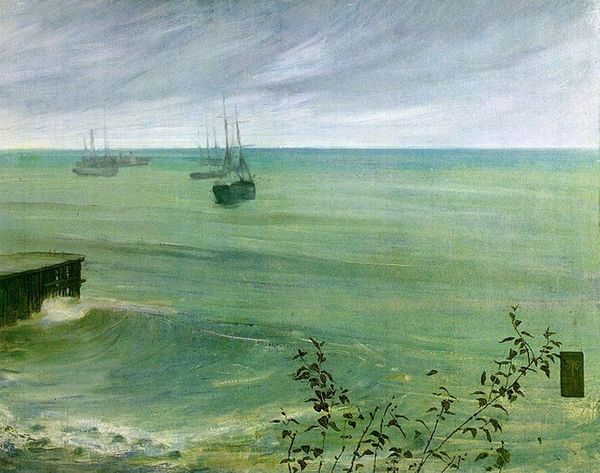

sea

Dimensions: 12.3 x 21.6 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: We're looking at James McNeill Whistler's watercolor, "Grey and Silver Mist - Lifeboat," painted in 1884. The delicate washes create a hazy, almost dreamlike seascape. I’m struck by how Whistler uses so few details to evoke such a specific atmosphere. What do you make of this composition? Curator: It is the artist’s reduction to essentials which dictates the impact. Note the structural elegance; the way Whistler employs horizontal bands of varying tonal value, subtly divided, creates a cohesive visual field. The very limited palette furthers this aesthetic project, harmonizing sky, sea, and shore. Editor: It’s interesting that you call it a "visual field." The almost total lack of contrast really minimizes any sense of depth, flattening the entire image. Is this deliberate, or just a consequence of the watercolor medium? Curator: That 'flattening', as you call it, is no accident. Observe the brushstrokes; they deny any deep recession. Whistler seems less interested in representational accuracy than in an exploration of form and color as self-sufficient entities. His work invites a decoding through close engagement with compositional syntax rather than with external reality. Editor: I see what you mean. Looking at it as an arrangement of shapes and tones makes the subtle gradations in color much more noticeable, like a study in tonal harmony. Curator: Precisely. How might the term “nocturne”, so frequently assigned to his work, relate to our understanding of the painting's mood or feeling? Editor: Well, there's definitely a quiet stillness. I think I appreciate Whistler's approach more now, recognizing the painting as less a representation and more an orchestration of visual elements. Curator: Indeed. Such a viewing permits an appreciation for art’s intrinsic, autonomous existence, moving past representational demands and towards an aesthetic ontology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.