Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

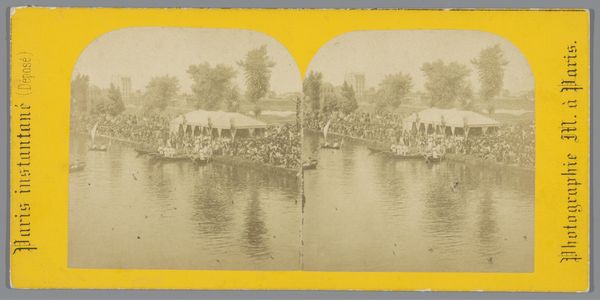

Curator: At first glance, this feels so still, almost like a held breath. All soft greys and reflections...it invites a kind of quiet contemplation, doesn't it? Editor: Indeed. What you're seeing here is an albumen print, a photograph from sometime between 1860 and 1880 by Ernest Eléonor Pierre Lamy, titled "Apollovijver in de tuin van Versailles," or Apollo Pond in the Garden of Versailles. It's quite characteristic of landscape photography from this era. Curator: There's something romantic about it too, I think. All that water blurring the edges, making the artificial pond look wilder, more mystical. Were the gardens meant to appear untamed? Editor: The gardens were anything *but* untamed, yet the image reflects that strain between control and nature that Versailles embodied. Louis XIV wanted to master nature to showcase his absolute power, of course. The pond with the gilded Apollo statue group celebrated the Sun King himself! It was designed and produced as a spectacle of power and elegance. And photographers would make stereo images of it like this, for the masses. Curator: It seems odd now, looking at a still photo, to remember the original *showiness* of Versailles. What about the choice of the print as the chosen media, why photography, though? Editor: By this point, photography was well established. This particular process – albumen printing – allowed for incredibly sharp detail but it also required extensive resources; from the glass plate negatives used to egg whites to provide the emulsion, all speak to the industrial scale and social function of photography in promoting state and national image construction. The photographs also offered a new perspective, as paintings and other pictorial forms of media were largely targeted to appeal to the upper-class group only. Curator: Thinking about those layers of visibility – or invisibility – what would it have meant to capture such grandeur at that particular moment in time? Were people aware they were constructing, and selling, not just a photograph but a certain story about France? Editor: Absolutely. The image is both documentary and highly constructed, selling this vision of French imperial residencies to a global audience. It subtly affirms France’s cultural and political position, packaged in a visually appealing format. This isn’t merely a snapshot, it's a statement. Curator: It all brings out an interesting mix of power and peace, doesn't it? The fountain itself frozen in time, like a caught memory...a carefully curated memory, at that. Editor: Yes, and to this day it continues to feed that global perception, as the world flocks to Versailles! I suspect Lamy would've known his imagery would carry well beyond his moment in time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.