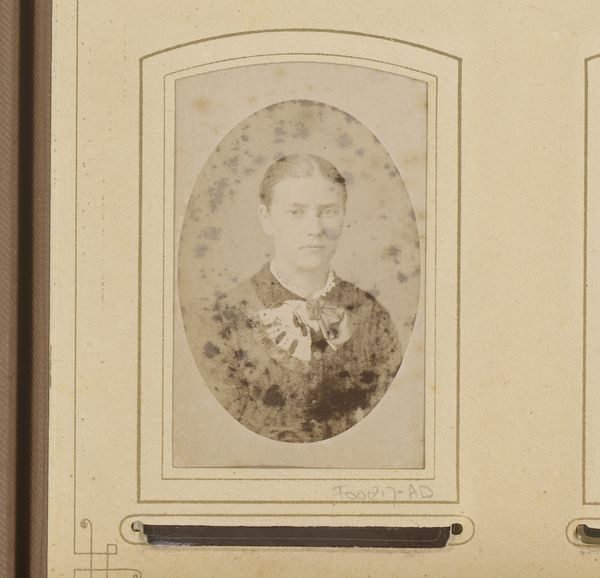

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Adrien Louvois's “Portret van een vrouw,” a gelatin silver print likely made between 1879 and 1882. It's a stunning example of late 19th-century portrait photography. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: My first impression is one of solemnity. The woman’s direct gaze and the faded sepia tones lend a weight to the image. It feels like peering into a distant past, and there is almost something ghostly about her. Curator: The formal photographic portrait was, of course, a burgeoning phenomenon during this period, coinciding with significant social changes. These portraits often served as a way for individuals, particularly within the rising middle class, to assert their place in society. It was a statement of their identity. Editor: Exactly. And for women, particularly, it could be a carefully constructed assertion of self. However, it is difficult to not also read a certain amount of conformity in her dress and tightly pulled-back hair. Is that a result of societal expectations or a conscious decision? What was photography's role in shaping women's identity during this time? Curator: That’s a crucial point. Photography, while offering new forms of expression, was very much a product of its time, reinforcing and sometimes challenging prevailing social norms. One could argue, though, that simply being photographed, choosing to participate, was itself an act of agency in a world that often sought to control women’s image and roles. Editor: I agree. There's a quiet resilience in her gaze that speaks volumes. Perhaps she is aware of her position and exercising a degree of self-determination through this very portrait. What do you think her access and ability to sit and engage with a photographer communicates about her life and positionality? Curator: We see the democratization of portraiture beginning in this period. That's also suggested by the presentation. While some damage is evident in this copy, we should consider how and why this image might have been contained, shared, and treasured. Editor: And, the way the print is aged makes me question its ability to function now, outside its context, and what it might communicate about identity, history, or the function of memory today. Thank you for allowing me to engage with that complexity. Curator: Of course. It’s precisely this kind of questioning that helps us appreciate these works and connect them to contemporary conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.