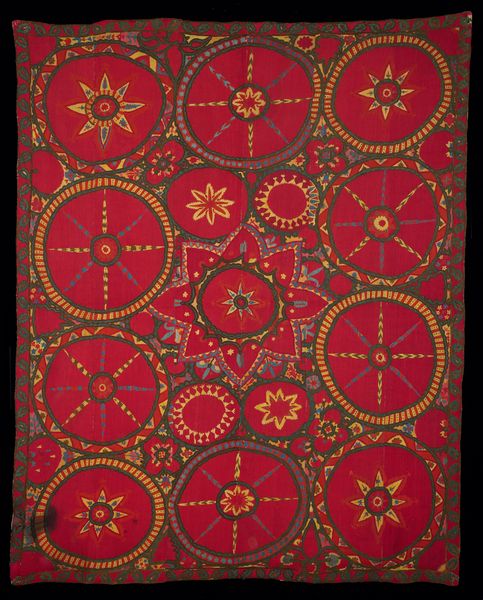

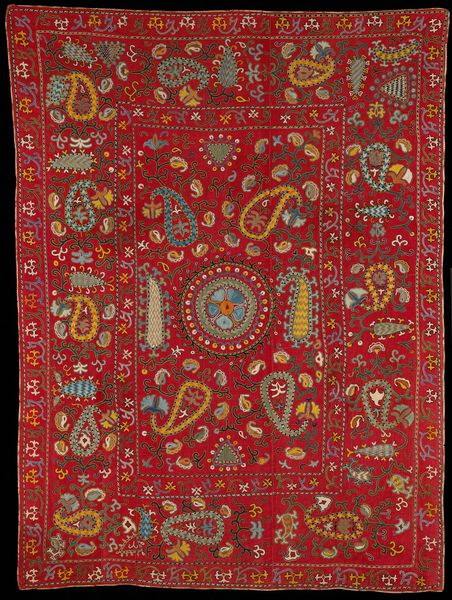

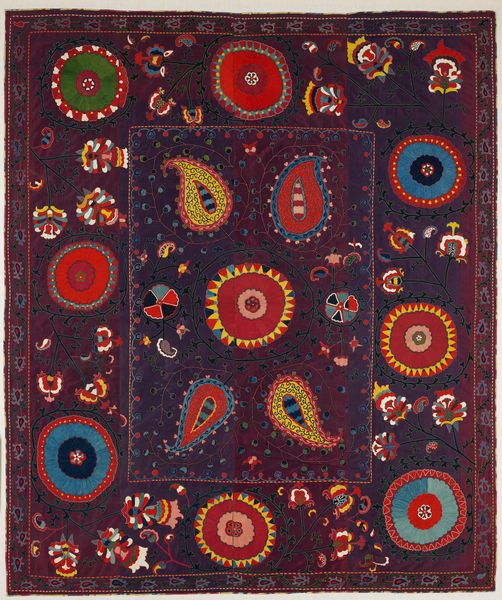

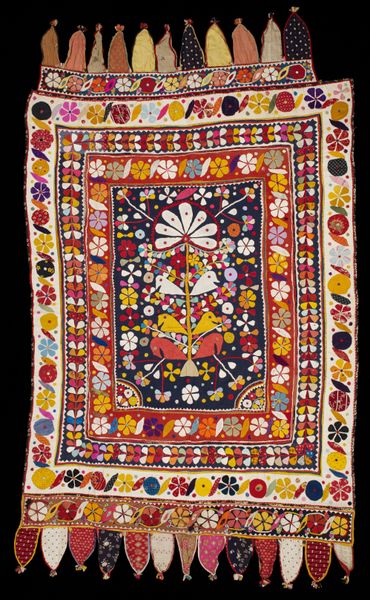

fibre-art, silk, textile

#

pattern heavy

#

fibre-art

#

naturalistic pattern

#

silk

#

loose pattern

#

pattern

#

pattern

#

asian-art

#

textile

#

abstract pattern

#

geometric

#

orientalism

#

repetition of pattern

#

intricate pattern

#

pattern repetition

#

decorative-art

#

layered pattern

#

funky pattern

Copyright: Public Domain

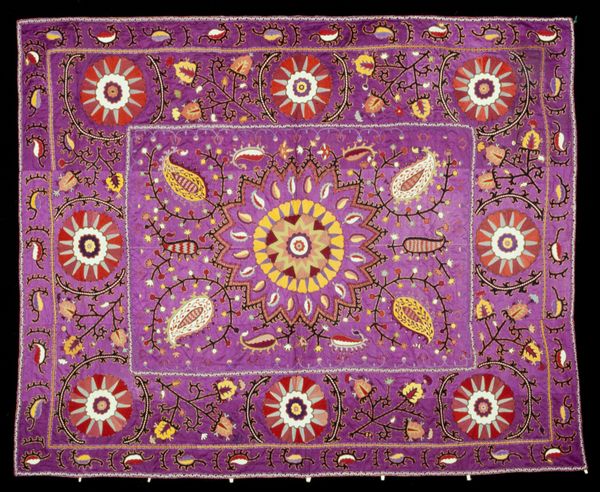

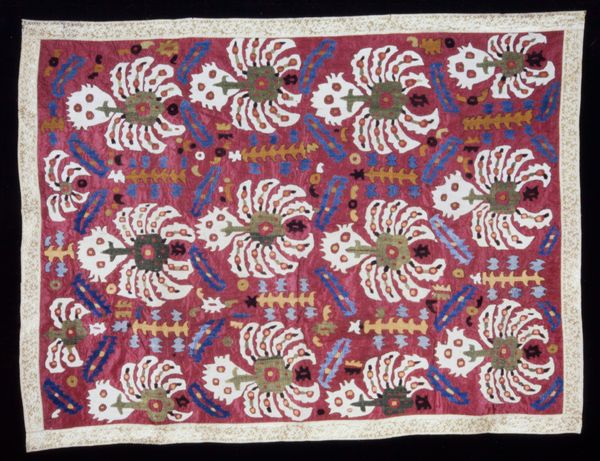

Curator: This vibrant piece is titled "Suzani," dating from between 1930 and 1940. The textile, worked in silk, finds its home here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: Oh, my! It hits you right away, doesn't it? That chartreuse ground with those fierce crimson floral bursts… It feels like a dream, a bit like stepping into someone else's wildly patterned memory. Curator: Indeed. "Suzani" originates from Central Asia, often Uzbekistan, and these embroidered textiles carried significant social and ceremonial weight. Specifically, the textile work can be interpreted in connection to wedding rituals, as symbols of union, fertility, and protection for new families. Editor: Wedding rituals… you can see it! A riot of life exploding outwards! All those seed-like shapes, almost aggressively fertile, bursting with potential, with a tiny halo around the larger blossom like the expectation of imminent divine intervention. I just want to wrap myself up in this riot of procreation and manifest. Curator: Consider, too, that while seemingly abstract, the motifs frequently represented specific hopes— pomegranate for abundance, for instance, or perhaps suns for vitality. There are geometric shapes here. Their creation was often a communal act led by elder women, reinforcing intergenerational knowledge and skills, and in its origins we understand it to be the intersectional agency of the women working with material in their surroundings. Editor: Communal labor, yes, you can practically hear the hum of shared purpose. This isn't just fabric; it's the echo of generations passing down stories with every stitch. A very earthy connection. There is no shying away from the cycle of life. Birth, death, and more birth again. Curator: Precisely. Furthermore, the appropriation of "Orientalist" aesthetic categories underscores a longer history of exchange and power relations inherent in how these works have been— and continue to be— circulated. Editor: So true. So the next time someone tries to convince me minimalism is the ultimate luxury, I will present this as evidence for a better and a much juicier way. Curator: An interesting point to sit with as we appreciate how material culture embodies both historical continuity and individual expression. Editor: And to think of art, especially women's work, as so much more than meets the casual gaze. Thank you for opening my eyes, once again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.