engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

limited contrast and shading

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

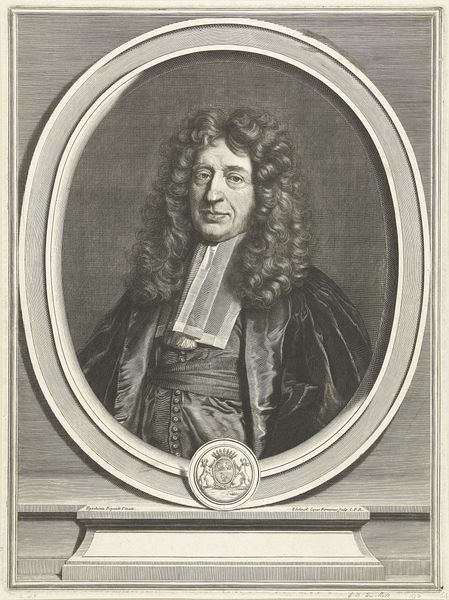

Curator: Here we have an engraving, likely from the late 17th century, "Portret van August Milag" by Andries Vaillant. Editor: There's something incredibly tactile about it, even as a print. The density of the lines forming those luscious curls…you can almost feel the weight of that wig. Curator: Exactly! It is important to consider how portraits functioned as tools of power during the Baroque era. Consider Milag’s role and social standing – evident through not just the attire but the inscription which proclaims him as 'Intimus et Cancellar Anhalt,' all carefully rendered to reinforce his authority. Editor: The engraving process itself is interesting. Think about the labour involved – each line carefully incised into the metal, building up the image bit by bit. You’re not just depicting someone, you’re manufacturing their image, literally stamping their presence. Curator: And this image, distributed through print, gains incredible reach. Prints like this disseminated ideas about status and leadership amongst wider society, beyond the court circles that would've viewed the original perhaps. Look at the formality of the composition, which places August Milag within very defined socio-political frameworks. Editor: The rigid framing, even the ribbon embellishments – they are not just decoration; they speak to established modes of presentation, of how the image itself is constructed for consumption. It speaks volumes about Baroque print culture and material constraints but also ingenuity, each carefully wrought line adding detail and texture. Curator: Agreed. Through these deliberate choices, Vaillant not only captured Milag’s likeness but solidified his public persona within the era’s visual language of power. Editor: So, the portrait isn’t just an artwork; it’s a meticulously crafted object, mediating social power via material means. It’s in the labour and technique, in those densely worked lines that its true value resides. Curator: Precisely, by examining portraits as disseminators of imagery within precise socio-political climates we gain far deeper knowledge of the period itself. Editor: Thanks, it does highlight how looking closely at materials and methods changes our reading of these images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.