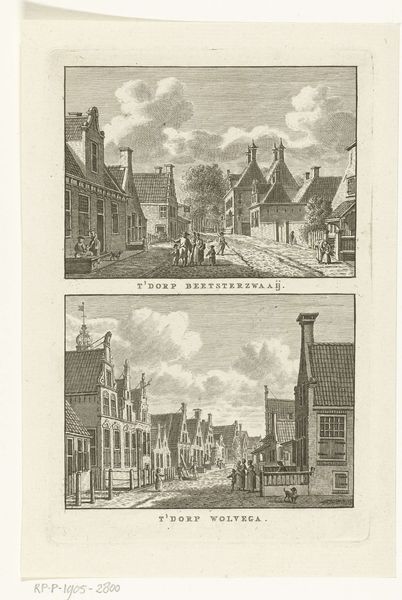

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

street

#

realism

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

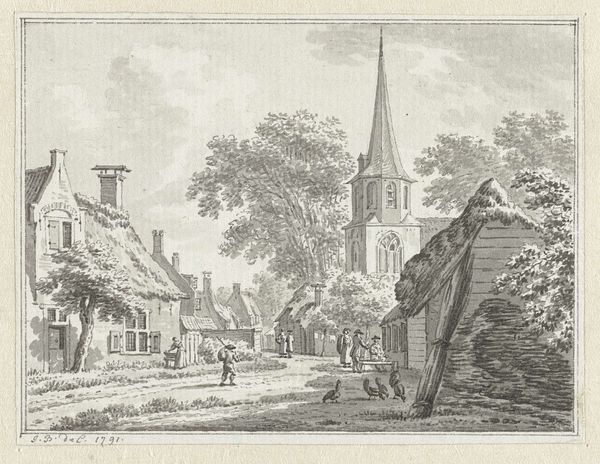

Curator: Ah, here we have "View of Zoutelande," a print, etching, and drawing created in 1792 by Jan Bulthuis. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your take as we approach? Editor: Well, right away, there's a calmness to it, despite the slightly ominous clouds overhead. It feels like stepping back in time, the scene steeped in this sepia stillness. The rooftops all slant, like whispers agreeing with the wind. Curator: It’s intriguing, isn’t it, how Bulthuis captures the domestic rhythms of the village? Note the material reality, all these repetitive tasks. There are people seated, at labor right on the doorstep. Observe how labor manifests itself right in the construction of the thatched and tiled roofs. The materials at hand dictate form, an unpretentious relationship with available resources. Editor: Exactly. And somehow, despite the realist depiction, there's an underlying symbolism here, perhaps unintended. This persistent cycle of domestic labor. How people persist, building homes with what is at hand. What stories do you imagine from looking into the distance? Curator: I’m more attuned to the foreground, the here and now. What sort of paper did Bulthuis use? Who printed this? It brings up larger considerations of art as work, art as craft. Not just an object of aesthetic appreciation but of labor, and what that says about social dynamics and value. It seems so at odds with later romanticism and emphasis on artist as tormented solitary genius, don't you think? Editor: It does, and maybe there’s also some resistance inherent to Neoclassicism. After all, it was birthed amidst the French revolution. But I feel the hint of a greater world in the cloudy sky. It evokes that longing, which might come about due to seeing this scene repeated day after day. Curator: I understand your longing. It gives an additional layer when seeing the means of production and thinking of consumption in society, especially as this piece comes into our present. A way of grappling with societal implications by considering how it came into being. It almost grounds the work for me. Editor: Well, thank you. That material grounding almost liberates me to just look at the art differently, as an individual expressing both the limitations of reality, as well as what escapes those constraints.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.