drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

nude

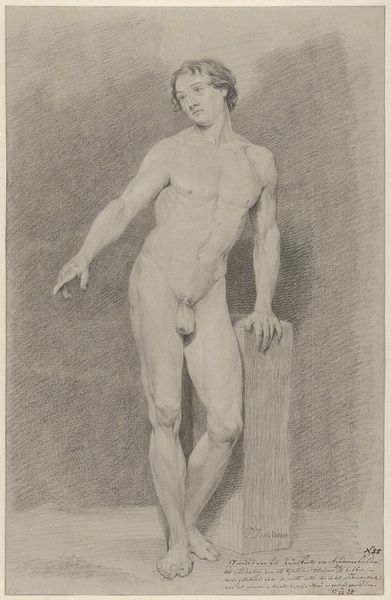

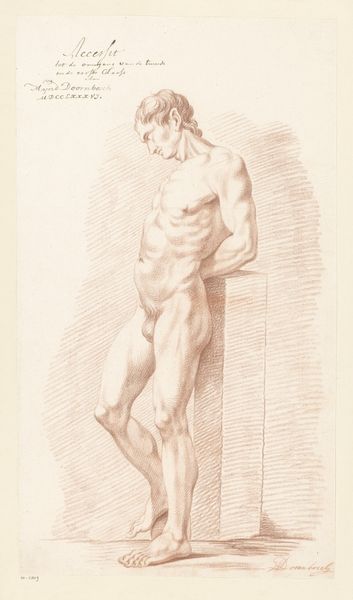

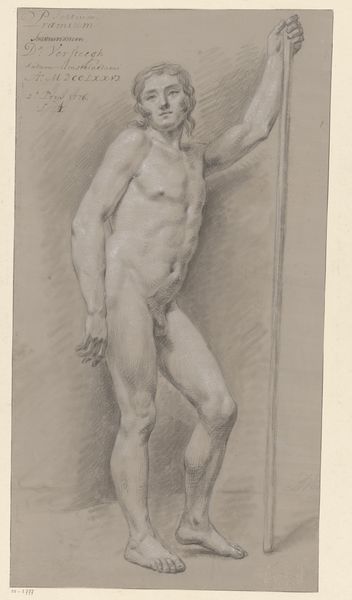

Dimensions: height 512 mm, width 308 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

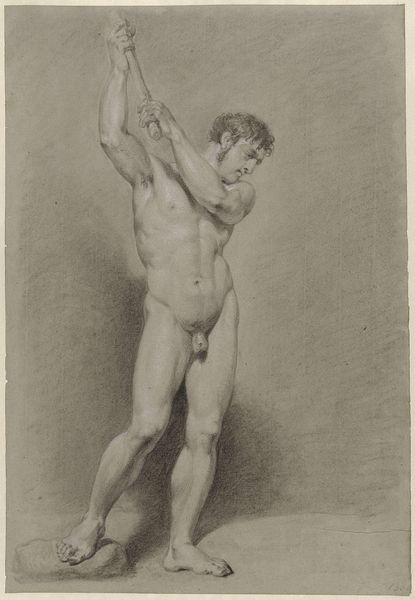

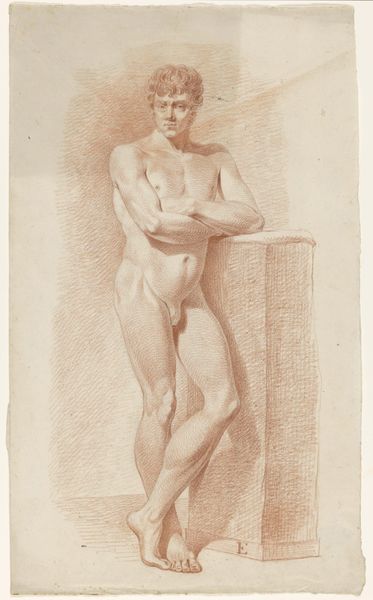

Curator: Let's discuss Hendrik Louw's pencil drawing, "Staand mannelijk naakt, van voren gezien (2e prijs 1781)," possibly completed between 1781 and 1782. Editor: My immediate impression is of delicate strength, if that makes sense. The soft pencil strokes create a sense of vulnerability, yet the pose and musculature suggest classical power. It’s quite compelling. Curator: Precisely! The artist is clearly engaging with Neoclassical ideals, striving for ideal form, order and balance through line and tone. Consider how Louw employs contrapposto. The subtle shifting of weight contributes to a dynamic, harmonious composition, perfectly echoing ancient Greek sculpture. Editor: I'm interested in the material reality here. Think about the graphite itself—where did it come from? Who mined it? How was it processed into a drawing implement, accessible enough for academic exercises yet capable of capturing such… rarefied ideals? Also, the paper... Curator: The paper does provide an interesting ground for exploring value contrast, certainly! See how Louw modulates the pencil pressure to create a full range of tones, skillfully modeling the figure and suggesting volume? His sophisticated handling of light and shadow conforms perfectly to Academic artistic practices of that period. Editor: Yes, but these materials existed and were circulated within economic structures that dictate artistic training. Someone had to make and sell those pencils. Consider how the second prize status also affects the object's meaning—a piece designed to win, existing in relationship to the very labor and economy that birthed the drawing materials and model? Curator: Fair enough, but focusing on those production conditions seems to overshadow Louw's manipulation of classical principles and visual construction. I wonder though, given your Materialist stance, is beauty possible in artworks produced in these unequal power systems? Editor: "Beauty" is culturally inscribed! Recognizing how a work is constructed changes its perceived value. For Louw, graphite, paper, his hours in the studio were shaped by both local production practices and larger socioeconomic ones! Curator: A fitting final thought, indeed. We should embrace this complexity when encountering the artist's fine draftsmanship and rendering. Editor: Agreed. Examining the pencil's path, in turn, adds layers to appreciating Louw’s historical context as well as technique.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.