painting, oil-paint

#

neoclacissism

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: overall: 44 7/8 × 57 1/2 in. (44 7/8 × 57 1/2 in.) framed: 144.78 × 176.53 × 10.8 cm (57 × 69 1/2 × 4 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

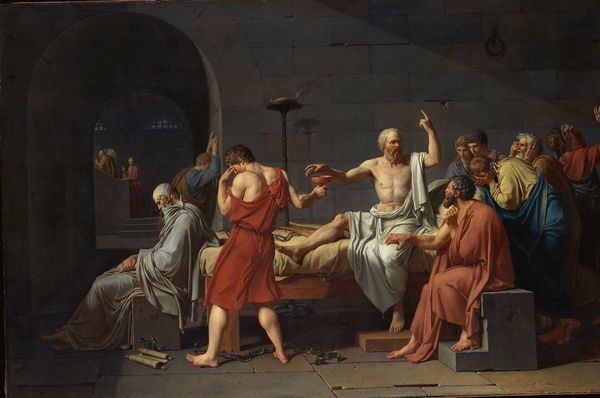

Curator: Looking at Girodet's "Coriolanus Taking Leave of his Family" from 1786, the immediate sense is one of heavy, almost staged grief. Editor: It certainly does. The stark light, the symmetrical arrangement, it all amplifies a kind of performative sorrow. I wonder how that intersects with ideas of masculinity and familial duty within the context of revolutionary France, just before things really exploded. Curator: Precisely. Girodet, as a student of David, consciously utilizes Neoclassical techniques—the idealized forms, the controlled brushstrokes—to portray a pivotal moment in Roman history. But what story is he trying to tell about power, about leadership? Coriolanus is leaving, exiled from Rome. We see his wife and children imploring him, desperate. Editor: And his resolve seems unmoved, which I think raises an important question: whose agency are we really seeing? His family are pleading with him; the other men on the left are anguished, while he…stands. His supposed strength seems more like emotional unavailability, perhaps even cruelty. I am curious about what it tells us of the socio-political constraints of masculinity. Curator: Right. There’s this very staged tension between the private, domestic sphere, largely represented by women, and the public, political realm Coriolanus embodies. And Girodet’s technique, despite its apparent classicism, is doing something very subversive by painting the space this separation opens between public expectation and lived consequences. Editor: Looking at it that way—especially in light of the period—I cannot help but think that the staging makes perfect sense to expose power relations between male "rationality" and its consequences within the domestic, intimate spheres, as spaces that are not quite separate from politics. It creates some friction when assessing these ideas. Curator: Agreed, I would further stress that his exile is based on his being labeled an "enemy of the people". So perhaps this is a portrayal of his ultimate sacrifice, framed to garner public support via sentimentality, to the detriment of the feminine private sphere. Editor: Interesting. Perhaps those constraints also illuminate contemporary anxieties about what the revolution was actually promising, at that specific moment in time, if only we ask whose freedom is being valued. It also helps bring some depth to our understanding of Coriolanus' image beyond his sacrifice and alleged lack of consideration for his loved ones. Curator: Absolutely, seeing beyond sentimentality leads to acknowledging the full extent of these sacrifices, which prompts us to recognize these images as crucial reminders of the contradictions inherent in both revolutionary and personal ideals.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.