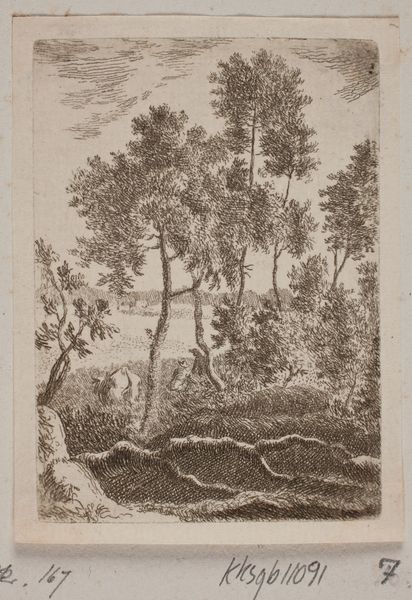

drawing, etching

#

drawing

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this etching from 1809, "Landschap met twee vrouwen bij een beek," by Ignatius Josephus van Regemorter. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Mmm, instantly I feel a sort of hushed reverence. It's delicate, the way the light seems to just whisper through those trees. Makes you wonder what secrets they’re sharing with the stream. Curator: Yes, that subdued tone aligns well with the Romantic landscape tradition. Consider the labor involved in such detailed etching; the painstaking work that translates nature's grandeur to a reproducible image intended for a rising middle class. The materiality itself underscores access. Editor: Absolutely, but there’s also a kind of… loneliness? Despite the figures, the scene feels remote. It speaks to this longing for untouched spaces, an almost primal pull, no? Or am I just projecting my Monday morning ennui? Curator: No, I agree there’s a sense of melancholy. This corresponds to Romanticism's preoccupation with emotion, particularly in contrast to industrialized labor practices and burgeoning class structures in society. Etchings like this depicted an idealized nature as refuge, an escape commodified as easily distributed print. Editor: That's so interesting how you put it. For me, it’s the mystery of the two women that gets me. What are they doing? What are they talking about? They seem both completely immersed in their world and utterly indifferent to our gaze. Curator: Their placement also demonstrates that tension. While "figuration" places humans inside landscape, Romanticism also valued the sublimity of an unpolluted world--the very presence of figures changes the reading of the image, doesn’t it? Their placement as subject and disruption? Editor: Hmm. Subject, certainly. But "disruption"? Perhaps the industrial revolution, then an art consumer, considered human subjects a disruption—but maybe Regemorter wasn’t concerned, focused on how women were a part of nature. And their labor, though unrepresented, is as important in your argument. I keep returning to that quiet exchange, so central. I want to know what they were seeing! Curator: That tension makes it so compelling. Well, I appreciate how you make visible unseen, working hands of history. Editor: And I find the art richer by looking for both—visible and invisible, objective and speculative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.