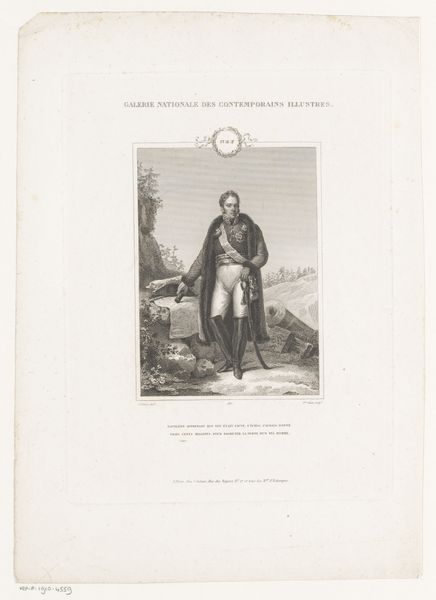

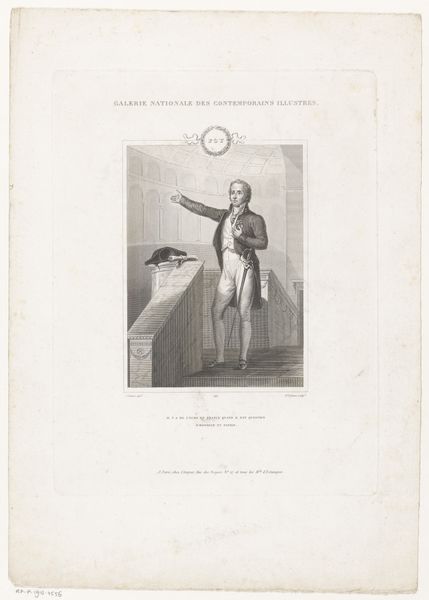

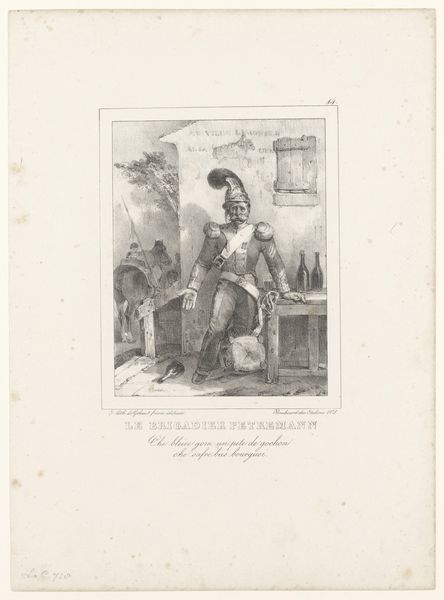

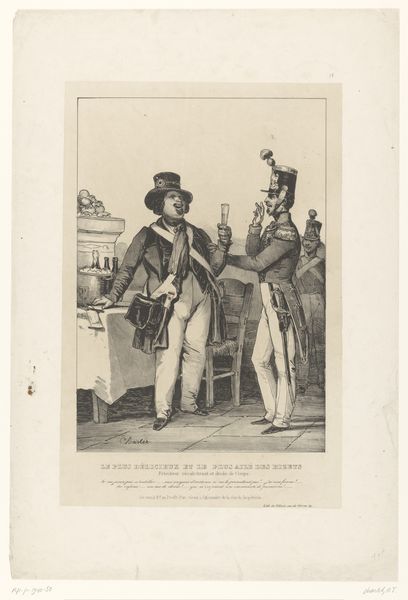

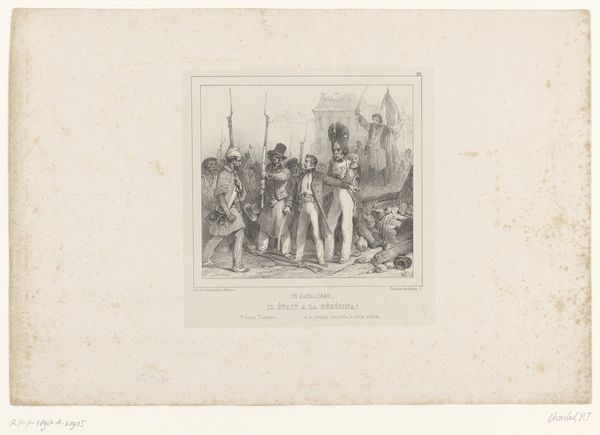

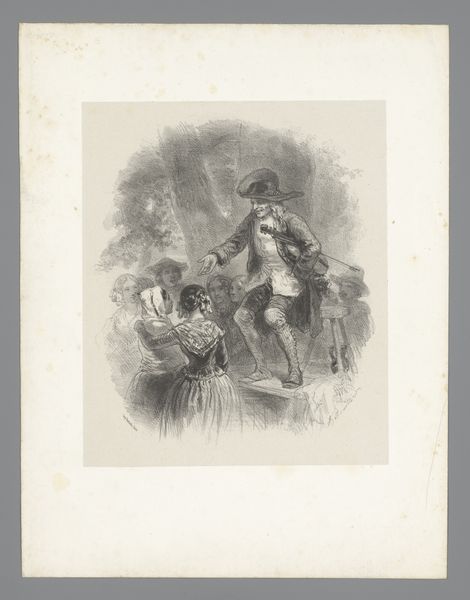

print, engraving

#

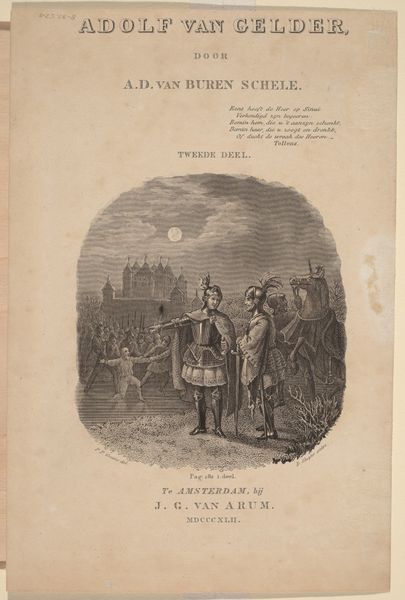

portrait

#

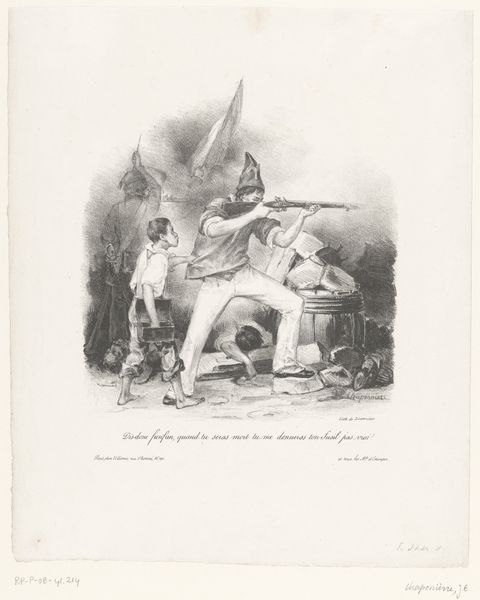

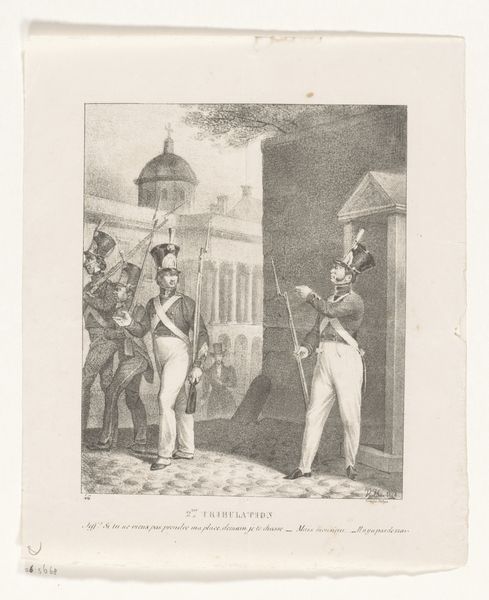

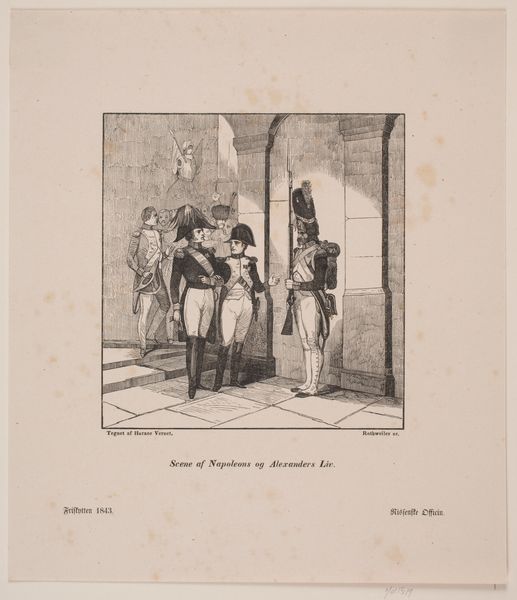

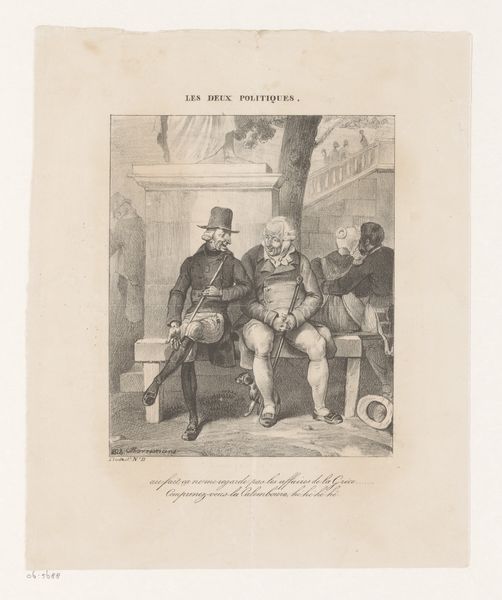

pencil drawn

#

neoclacissism

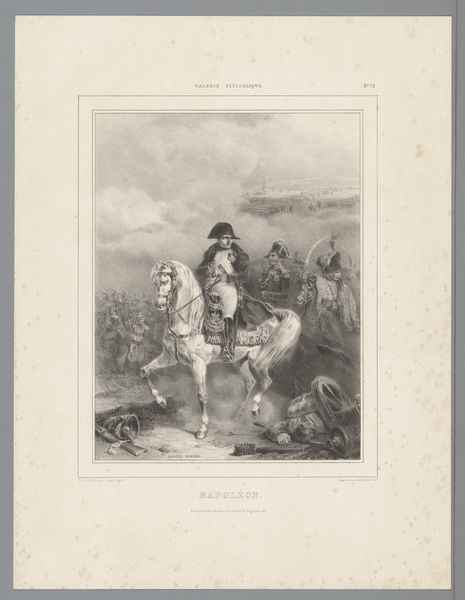

# print

#

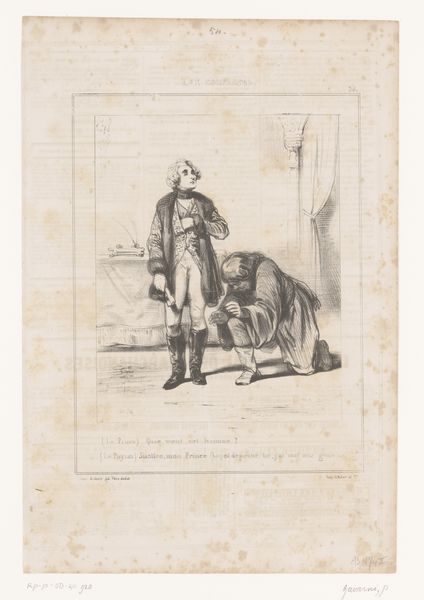

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

pencil work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 225 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So here we have "Portret van Étienne-Maurice Gérard," made in 1831 by Pierre Michel Adam, it looks like an engraving. It feels… official, like a carefully constructed image of power, yet the lines are delicate. What strikes you when you look at this piece? Curator: Ah, yes. Immediately, I’m struck by the tension—the rigid pose of Gérard juxtaposed with the rubble around him. He’s so clearly meant to project authority and stability. It’s almost theatrical, isn't it? Look how his sword mirrors the line of the French flag behind him. That intentional mirroring, it’s pure visual rhetoric! It practically screams "leader!" Editor: Rhetoric indeed! So it’s not just a portrait but a statement? Curator: Exactly. Think about where this sits, historically. 1831 – the July Revolution was still fresh. Images like these weren’t just art, they were carefully crafted pieces of political messaging, attempts to shore up power and project an image of unwavering control in a pretty unstable time. Tell me, does that change how you view the 'delicate' lines you noticed? Editor: Definitely. What I initially saw as a softer artistic choice, now feels like a calculated decision to perhaps humanize a figure of authority during a time of upheaval. I’ll definitely think of portraits differently now, considering the context they were created in. Curator: That’s it exactly. To look closely, isn't just to *see* – but to unravel intentions and histories. It’s why I always find myself peering in a historical mirror, whenever art beckons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.