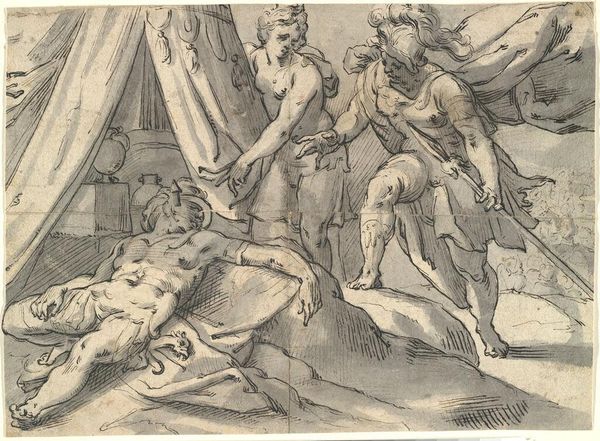

drawing, print, paper, ink, chalk, pen, charcoal, black-chalk

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

ink painting

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

chalk

#

pen

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

black-chalk

Dimensions: 182 × 247 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "The Mocking of Christ" created by Andries Both between 1633 and 1635. It’s rendered in ink, chalk, pen, and charcoal on paper and now held at the Art Institute of Chicago. I’m immediately struck by how the artist captures the cruelty of the moment. How do you interpret this work, especially given its historical context? Curator: The scene is undeniably brutal, and situating it within the context of the Baroque period is crucial. But how does Both engage with the politics of religious representation and power? Look at how Christ is centered yet seemingly vulnerable. His suffering is foregrounded, but the active expressions and gestures of those mocking him – filled with what? – contribute to the scene’s complex emotional dynamic. It's a narrative of social control, highlighting the abuse of authority. What does that evoke in terms of intersectional narratives involving race, gender, and politics? Editor: It makes me think about the vulnerability of marginalized groups throughout history and how power structures have been used to oppress individuals. But it is also about how the narratives are framed from a perspective. Curator: Precisely. Consider also Both's choice of medium. Black chalk, pen and ink often were used for preparatory studies. What impact does it have to view the Passion cycle of Christ as an expressive "sketch" rather than a highly polished, finished history painting on canvas? Does the seemingly incomplete, spontaneous design expose the constructed nature of even sacred events? Editor: That’s a fascinating point! Seeing it as a sketch makes it feel more raw and immediate, like a snapshot of injustice. It highlights not just the event but also its construction and the social dynamics at play. It’s like a powerful piece of activist art, even from centuries ago. Curator: Absolutely. And by reflecting on these connections, we gain a more profound understanding of how historical artworks can inform and challenge contemporary conversations about power, identity, and representation. Editor: I see it in a completely new light now, thinking about its role in larger cultural and political dialogues across time. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.