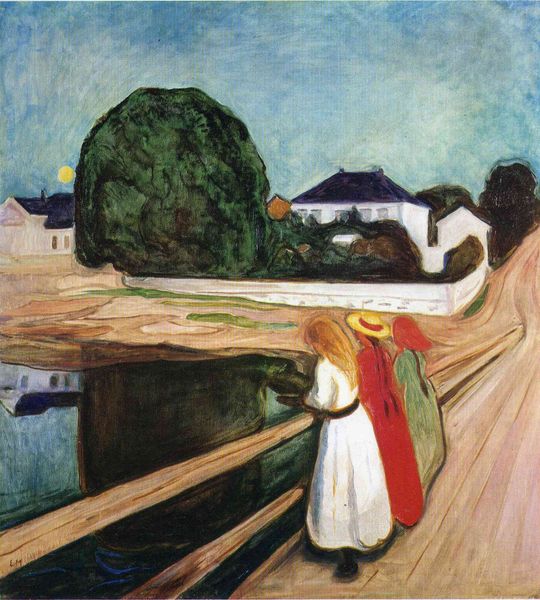

Copyright: Public domain

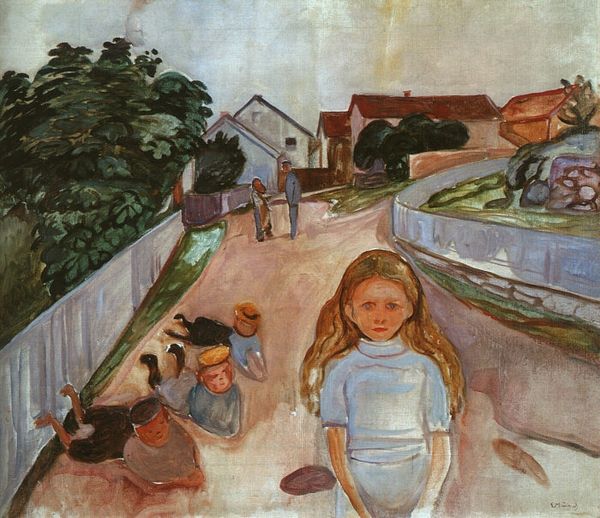

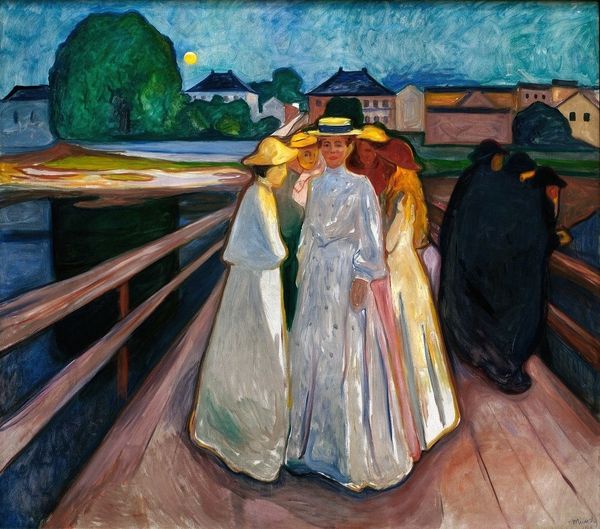

Curator: So, we're looking at Edvard Munch's "Girls on a Bridge," painted around 1900. It's currently held in a private collection, though it's one of Munch's most recognizable works. What strikes you immediately? Editor: The color. It’s unexpectedly vibrant. Not at all the angst-ridden gloom often associated with Munch. There's a definite visual tension between the warm hues of the girls' dresses and the cool tones reflecting in the water. Curator: It’s interesting you say that, because even here, away from "The Scream," Munch explores themes of isolation and societal pressures, just with a different palette. These aren’t simply girls on a pleasant stroll. Editor: I can see that. The composition funnels our gaze toward the girls. It's the repetition of vertical lines – the bridge supports, the figures themselves – creating a sense of confinement and directionality. A movement into shadow perhaps? Curator: Exactly. Consider the historical context: the painting reflects anxieties surrounding the transition from rural life to urban modernity in Norway. The girls stand on this bridge, this threshold. They are on the cusp, symbolically caught between two worlds. This bridge is not simply infrastructure, but a social marker. Editor: From a purely visual perspective, note how Munch employs a restricted palette and broken brushstrokes reminiscent of Impressionism, yet the flatness and simplification hint at something modern as well. Also how that black mass is mirrored below. Curator: Indeed. Munch was engaging with, yet also pushing against, the established artistic movements of his time. The image became immensely popular and began to function as commentary of feminine life at the beginning of the modern age, when ideas about gender were widely being debated, both culturally and scientifically. Editor: Looking again at the formal components in the work—how the bridge’s converging lines create depth but also a sort of instability—creates a strong push and pull on the picture plane and in its psychology. The brush strokes add tension and uncertainty in our viewing experience as well. Curator: In short, we're left to contemplate the unspoken narratives suggested within the formal constraints imposed by the work’s own history of viewing. This invites viewers to bring their own experiences and projections to the experience of femininity in 1900. Editor: That’s a really helpful perspective, viewing the image in terms of its formal language reflecting greater societal shifts and stresses, and how the girls and bridge create the architecture of a metaphor of progress and industrial growth. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.