photography, collotype

#

water colours

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

landscape

#

traditional architecture

#

photography

#

collotype

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

19th century

#

cityscape

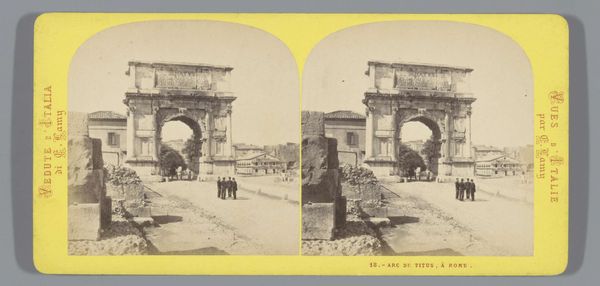

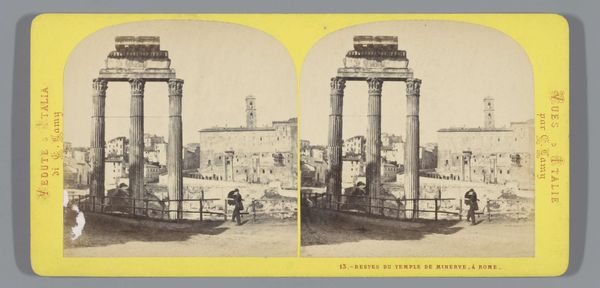

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Jean Andrieu's "Gezicht op de Boog van Titus," a collotype dating from somewhere between 1862 and 1876. There's a certain stillness to the image, despite it depicting this massive architectural monument. I'm curious, what historical context helps illuminate our understanding of it? Curator: Well, the proliferation of images like this one in the mid-19th century really speaks to the rise of tourism and a burgeoning visual culture. Consider that photography was still relatively new. What would it mean for the masses to suddenly have access to scenes from distant lands? Editor: So, it's about accessibility and dissemination? Like a postcard, almost? Curator: Precisely! Think about how images of Rome, with its layered history of imperial power and artistic achievement, served as potent cultural symbols. This photograph wasn't just documenting a ruin; it was actively constructing a particular narrative of European history. What do you think that narrative emphasized, given the political climate of the time? Editor: Perhaps the grandeur of the past, tying into contemporary ideas of nationhood and empire? I can see how these kinds of images would legitimize claims of power. Curator: Exactly. Andrieu’s work and others’ weren’t neutral records, they were involved in the circulation of specific ideologies. These were consciously shaped to influence how the public understood the present by presenting a certain version of the past. Editor: That’s fascinating. I never thought about how a simple photograph could be such an active participant in shaping cultural identity and political discourse. Curator: It’s a reminder that even seemingly objective records are embedded within power structures. What do you make of that in relation to today's media environment? Editor: I see how crucial it is to consider not just what we see, but why and how it's being shown to us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.