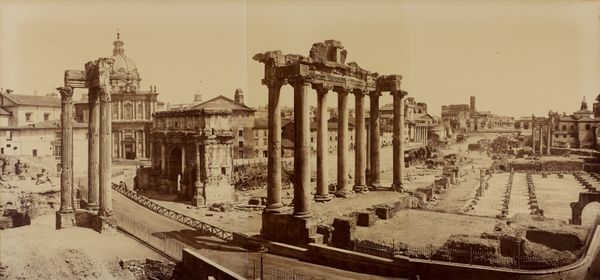

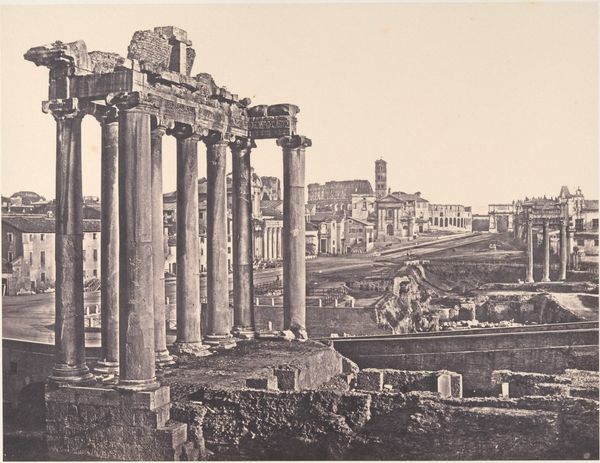

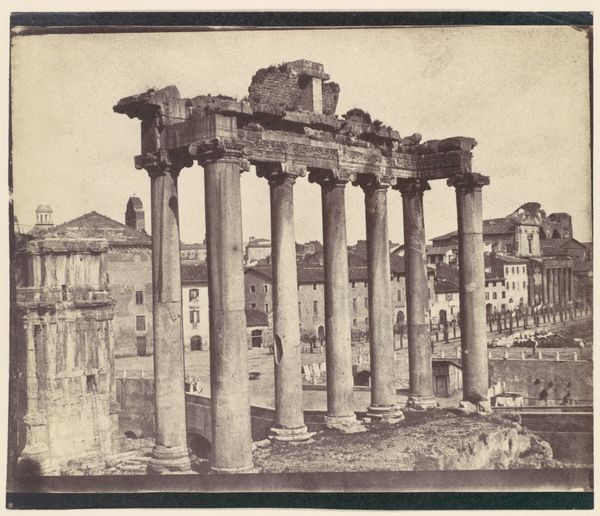

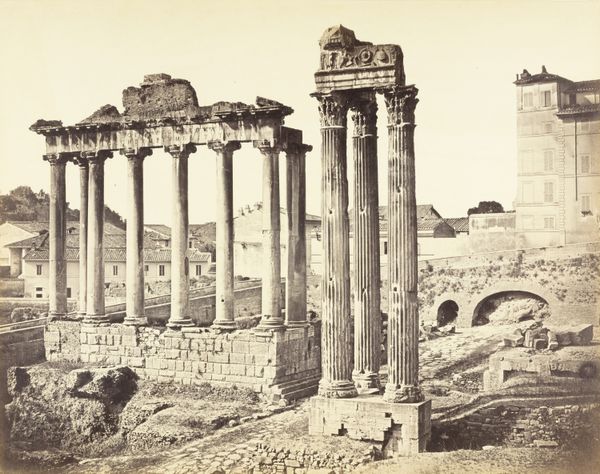

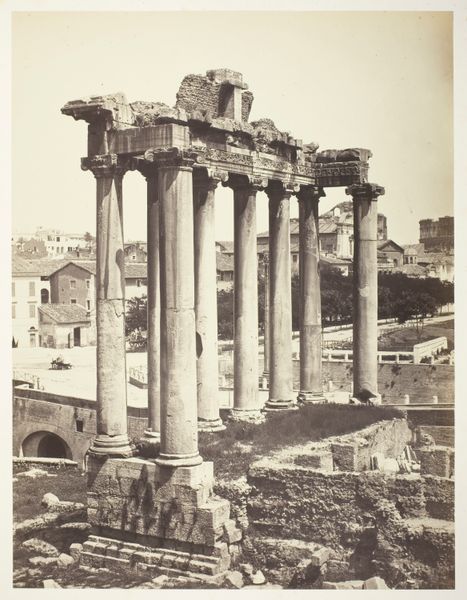

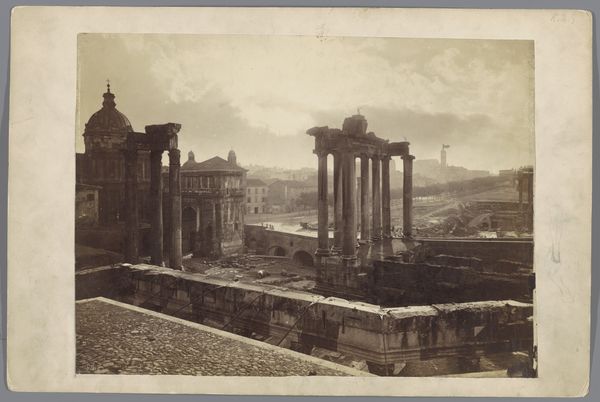

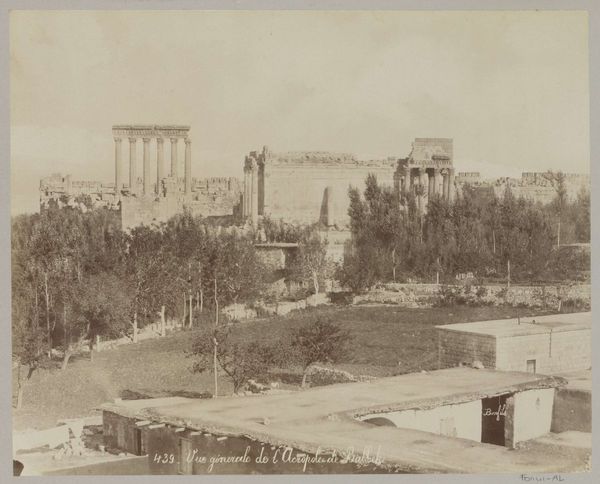

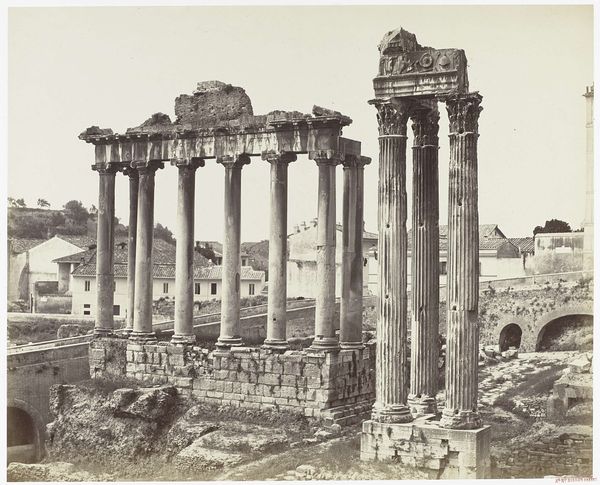

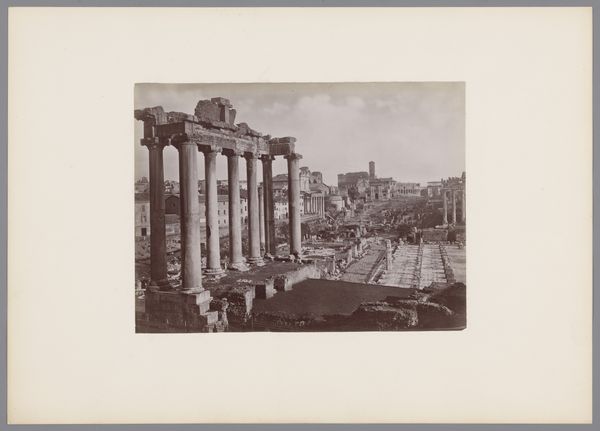

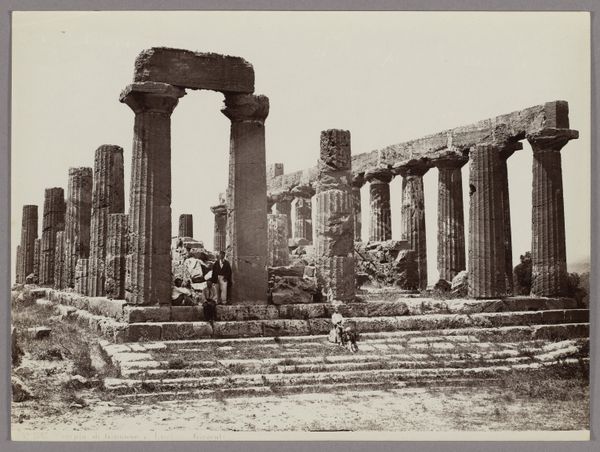

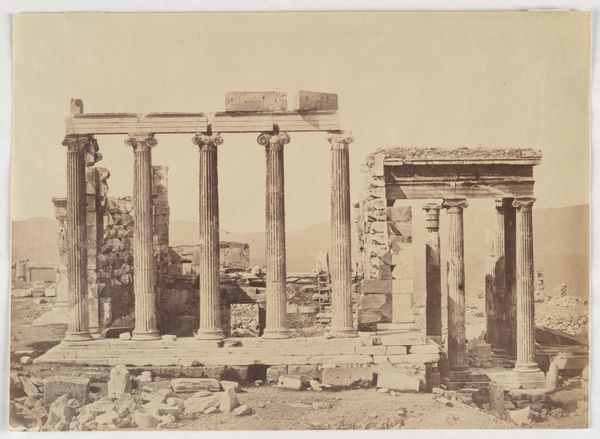

Rome, Vue Prise au Forum (Rome, View of the Forum) 1858 - 1859

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

landscape

#

historic architecture

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

cityscape

Dimensions: image/sheet: 26.4 × 36.9 cm (10 3/8 × 14 1/2 in.) mount: 48.3 × 59.8 cm (19 × 23 9/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: What a striking image. This gelatin silver print is entitled "Rome, View of the Forum" by Gustave de Beaucorps, and dates between 1858 and 1859. Editor: It's remarkably still, almost haunting. The ruins seem to rise like specters, stark and imposing against the muted backdrop of the city. It whispers of forgotten power and the inevitable decay of empire. Curator: Absolutely. Beaucorps, working in the mid-19th century, was very conscious of photography's capacity to not simply record, but to interpret the past. The Forum, even in its ruined state, spoke to a powerful imperial history that shaped western civilization. The question of whose history is being venerated, and what narratives get centered, is particularly important to examine. Editor: And consider how the image itself might serve a colonial gaze, packaging Rome's glorious past for consumption by Western tourists. There's a certain melancholy, a romanticization of the past that arguably sidesteps more pressing social issues of the period. Is it nostalgia, or something more insidious? Curator: A compelling point. There's a careful framing at play here. Beaucorps chose a specific viewpoint, highlighting the grandeur of the ruins while perhaps obscuring the everyday life and struggles of the contemporary Romans living amongst those ruins. Photography in this period became another tool through which societal structures, power dynamics, and national identities were shaped and disseminated. Editor: And yet, the photograph also bears witness to the city's layered history, visible in the diverse architectural styles rising around the Roman structures. It's a powerful reminder that Rome never really disappeared, it just changed, evolved. Curator: Precisely. The image pushes us to confront complex layers. On one hand, we admire the artistic choices. On the other, we need to also recognize that historical narratives aren't unbiased; they are often laden with dominant ideologies. What responsibilities, then, do we have to interpret those historical photographs in ways that consider excluded viewpoints and narratives? Editor: It provokes a powerful and timely reminder to dissect, critique, and engage with the image—both then, and now. To question not just what's represented but why, and for whom.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.