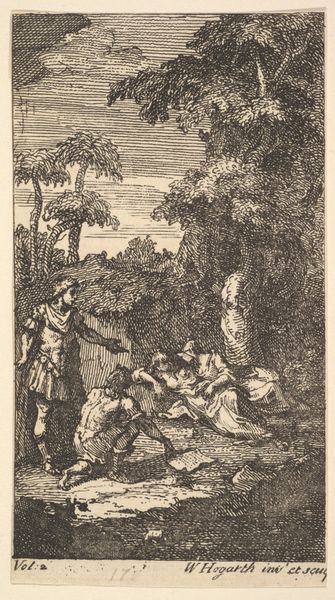

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 1/16 x 6 11/16 in. (23 x 17 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a 17th-century engraving titled "Epileptics Walking to the Left," created by Hendrick Hondius I in 1642. It's quite a compelling image, now housed here at The Met. What's your initial reaction to it? Editor: Well, immediately, I’m struck by the disorientation it evokes. The figures seem almost to be caught in a perpetual, unsettling dance, a whirlwind of shared distress. The etching possesses a sort of disturbing sympathy for its afflicted subjects. Curator: Indeed. It’s crucial to understand the societal context of the time. Epileptics were often marginalized, misunderstood, even feared. Hondius’s print, while perhaps not entirely free from the biases of the period, provides a glimpse into how such conditions were viewed and represented in art. Notice how the artist chose to display the group on the margins, excluded at a bridge. What are some recurring symbols you identify? Editor: I observe that several individuals are being supported, held up by others, as they convulse. These groupings read as a manifestation of a sort of support network, visually underlining community reliance in the face of individual suffering. It also reads a bit like ritual. Are they victims, performers, or perhaps some forbidden cult? Curator: That’s a thought-provoking reading. It prompts us to consider the potential performative aspect of illness in that era. Their portrayal challenges the traditional norms of representation and sheds light on a marginalized group within 17th-century society, a complex social dynamic. Editor: It certainly complicates simple assumptions. Also, consider the lone figure resting or abandoned, below a tree. Is it physical exhaustion, social ostracization, some form of treatment? The engraving suggests narrative threads beyond just documenting the illness itself, suggesting its broader social consequences. Curator: I agree. This image, beyond its immediate depiction of a medical condition, serves as a powerful testament to social attitudes and institutional frameworks prevalent in 17th-century Europe, and that period’s aesthetic representation. Editor: Yes, looking closely has helped me better contextualize the depth and sensitivity of the symbolisms and possible readings that we have before us here. I appreciate the layers here, and this moment to pause and consider the possibilities and the impact that such symbols hold to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.