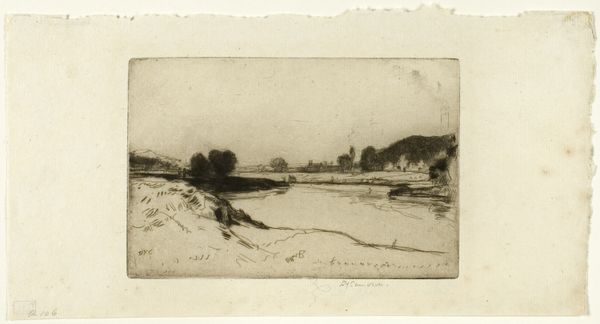

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

pencil drawing

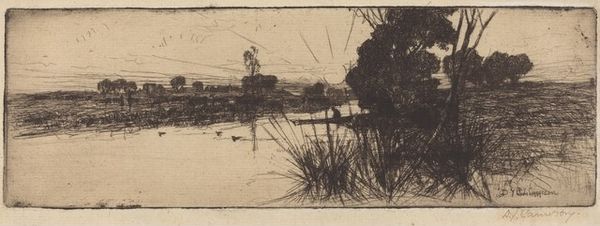

Dimensions: plate: 13.65 × 31.12 cm (5 3/8 × 12 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

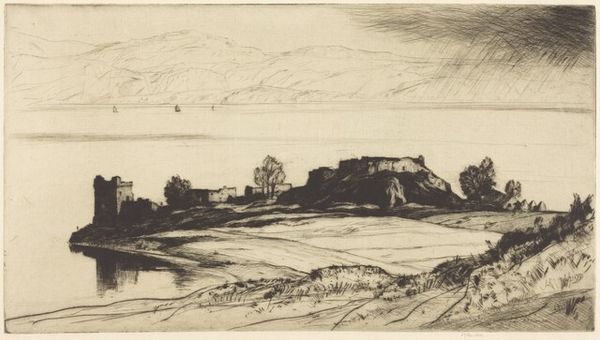

Curator: This is Muirhead Bone's etching, "Spring at Cardross," created in 1900. What strikes you initially? Editor: It’s remarkably stark. Even with the title suggesting springtime, the scene evokes a subdued mood, almost melancholic. There’s a visible roughness in the sky and land, conveyed through these intricate etched lines. Curator: The etching process itself plays a crucial role here. Bone was deeply engaged in the material possibilities of printmaking. Think about the labor involved – the meticulous scoring of the metal plate, the acid bath... it speaks to a dedication to craft. Editor: Precisely, and within its time this was being reproduced in an era that fetishized rural imagery for political and social uses. So who exactly was intended to own this, and for what kind of projection about the naturalized British countryside, its space and scale? Curator: An excellent question. Looking at Bone's approach, the density of lines creates dramatic shadows, focusing our attention on the textures of the landscape. The marks themselves tell a story of their own production. The print process allows one to reproduce identical imagery for mass consumption. What market desire was this playing into? Editor: Yes, this fits neatly within anxieties of turn of the century industrialisation. One could view it, even, as a commentary on power relations between the human subject and our physical context, made affordable via print media, but also somewhat complicated, perhaps even rendered complicit, by its method of manufacturing. Curator: It certainly resonates with broader trends in late 19th-century printmaking, where artists sought to elevate what had previously been regarded as simply reproductive processes. Editor: To push it even more perhaps, think about how representations of landscapes were used during this period to establish and reinforce colonial claims. A place of material value also had its ideological, racial, and national identity stamped onto it. Muirhead was not apart from that history. Curator: I see your point. So, reflecting on our conversation, it's fascinating how what appears to be a simple landscape can reveal layers of materiality and broader societal influences when you delve into its creation and context. Editor: Absolutely. And I would add, we as critics today carry the same imperial legacy into the space we analyze it now. These artifacts become part of a continued political context beyond their creation and original audience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.