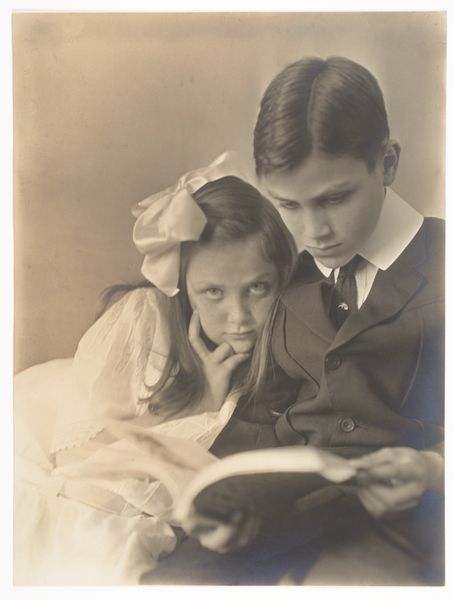

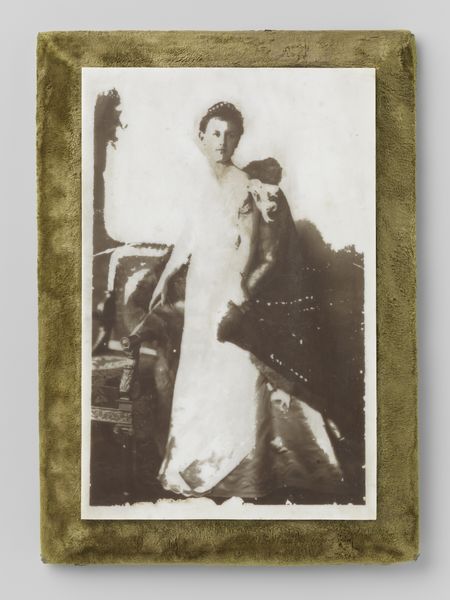

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

men

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: Image: 17 × 21.8 cm (6 11/16 × 8 9/16 in.) Mount: 21.2 × 28.9 cm (8 3/8 × 11 3/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "Mary Constable and Her Brother," an albumen print made in 1866 by Oscar Gustav Rejlander, currently held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It has this melancholic beauty, doesn’t it? The way the light catches the brother's face and falls away, makes me think of a fleeting moment suspended in time. Curator: Absolutely. Rejlander was a pioneer, merging art and photography in a way that challenged conventional portraiture. The subjects, especially in the 1860s, are often styled or posed in such ways to communicate narratives or meanings through dress or positioning. Editor: What stories do you think they are trying to tell? The girl has a wonderful look that almost pierces me. She almost makes me wonder what future awaits her. There's a gentleness and solemnity that captivates me. Curator: The social history of photography at this time certainly is relevant. As photography became more accessible to the middle classes, we see a democratizing shift, but at the same time the style, composition, and dissemination of photographic portraits also had something to do with social mobility and aspirational visual languages. How these images were made and viewed—who got to own an image—is crucial for our understanding. Editor: And the setting, deliberately nondescript, is meant to focus on the human relationship. Her arms clasped gently around his shoulders, as if she is somehow aware he will face an invisible, difficult world alone. Curator: Yes, the intimacy of the brother-sister dynamic—the slight lean, the mutual gaze, this is carefully composed. It makes me consider our desire to create enduring visual markers of memory—and Rejlander provides a glimpse into how relationships of siblings was a kind of popular trope or symbol of belonging during his time. Editor: Looking at it closely, it feels both intimate and a bit constructed, almost staged, like a tableau vivant. That might sound bad, but it isn't—it only shows that he knew how to show affection. It is hard to imagine posing affection, though I know there are people that do. Curator: It is true that Rejlander experimented heavily with combination printing. Whether or not this image involves that process, there’s a heightened sense of aesthetic control. To understand the popularity of sentimentalized kinship relations, one also must keep in mind that this was also an important moment when industrial capitalism made families anxious over the disappearance of more bucolic, agrarian life worlds. The politics of such longing is apparent everywhere in images of families in 19th century photographic portraiture. Editor: Seeing it that way...changes the way I interpret her look...Thank you for illuminating aspects of social history. Now when I observe her in the future, my memory will add what you mentioned. Curator: It's been a delight to reconsider Rejlander with you—a moment to remember our longing as viewers today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.