drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

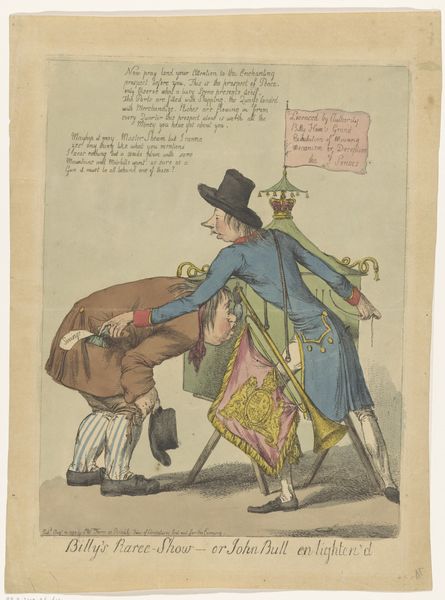

Curator: Thomas Rowlandson’s "Man voor een kijkkast," created around 1800, greets us with a disarming sort of casualness. Its light watercolour wash and gentle lines draw me right in. What catches your eye initially? Editor: Well, aside from the blatant phallic flag, the immediate sense is one of implied deception. It’s a satirical tableau, painted in the softest hues—deceptive in itself. Curator: The composition directs our gaze insistently toward the box itself. Notice how the central, orthogonal lines of the box are contrasted with the curvature in the figures' posture? What’s at play there, I wonder? Editor: It plays with the historical symbolism of spectacle. Rowlandson is latching onto that ancient connection between sight and knowledge. This box promises "all the wonders of the world," mirroring Renaissance cabinets of curiosities—but on closer inspection, what exactly *are* these wonders? Curator: The inscription, almost childlike in its looping script, reads, "Put your eye close to the glass, and you will see all the wonders in the World". Irony pulses beneath the surface; the phrase "all the wonders" seems bombastic when yoked to such a plain device. Editor: Exactly. It's less about seeing wonders and more about the act of *believing* you are. And this harks back centuries, a primal form of propaganda and visual seduction. The symbols, you see, build a chain, linking that peepshow operator with rulers promising earthly paradises. It is, in sum, visual criticism of human frailty. Curator: True, there's a certain fragility suggested by the delicate line work; a lightness that underscores the inherent flimsiness of constructed fantasies. Even the artist's color choice—almost faded as if seen through that glass—contributes to a critical understanding. The work suggests a deep reflection on the illusions we willingly construct and participate in. Editor: Agreed. And while the work feels decidedly eighteenth century, those themes are, undeniably, alive and well today. A potent work!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.