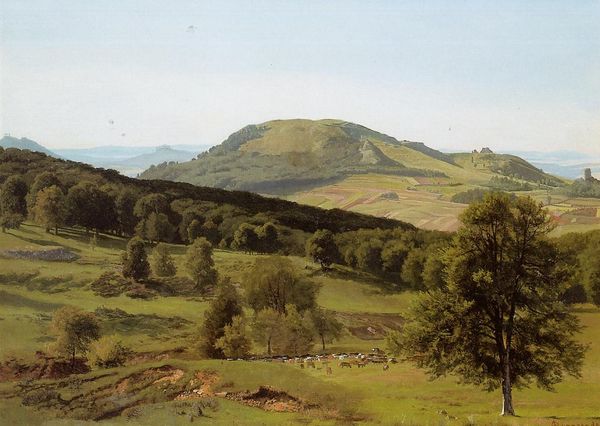

Copyright: Public domain

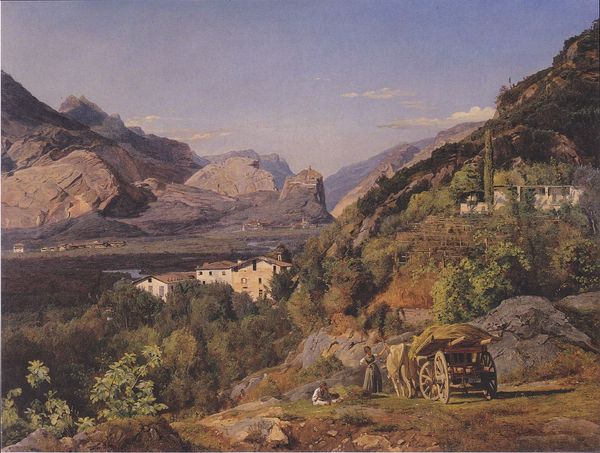

Editor: Here we have Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller’s 1862 oil painting, "Mountain landscape with vineyard." There's something about the subdued light that makes the scene feel peaceful, almost like a memory. The way the mountains fade into the distance creates a sense of vastness. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: It's interesting that you pick up on the atmosphere first, because for me, Waldmüller’s realism—his almost fanatical devotion to detail—creates an intense sense of *presence*. Notice how the light, as you said, isn't just atmospheric but carefully rendered to show the texture of the leaves, the earth. Do you see how the vineyards aren't simply green but a mix of ochres and browns, reflecting the local soil? He is trying to capture this landscape very precisely and celebrate it! Almost in the way one celebrates their local *wine*. Editor: That’s a great point. Now that you mention the textures, it's like you can almost feel the earth under your feet. Were artists commonly so literal when rendering nature, in 1862? Curator: It was the era of Realism, remember. Artists moved away from idealizing landscapes in favor of portraying what they *actually* saw, rather than what they thought they should see. The burgeoning Industrial Revolution had many longing for untouched landscapes as cities grew in size and pollution increased. What do you see in this contrast? Is this just pure painting of the world as it is? Editor: That really makes me think about what we value and choose to preserve. I came in with a mood, and you challenged me with literal details. This makes this landscape a bit sad to see now. Curator: Right! These conversations around preservation started with Romanticism, and perhaps Waldmuller wanted us to engage with nature this way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.